Race & Ethnicity

Upon induction, America’s World War II troops entered a military world rife with color lines—and rife with efforts to resist and rewrite them. The latter succeeded at making changes to the former. But, at war’s end, an entrenched and expansive set of racisms remained. In an excruciating irony that still stings more than three-quarters of a century later, America fought its “war for Four Freedoms” with a military steeped in white supremacy.

Jim Crow in Uniform

This white supremacy was most widespread regarding African American soldiers. Throughout the war, for example, they faced a complex, ever-changing, and ultimately successful campaign on the part of the military’s highest brass to block or limit their enlistment. True, some walls came down during the war—especially in the navy, the marine corps, and the army air corps—thanks to unstinting Black activism, alongside the growing need for troops. But strict limits always remained. Indeed, without them, the military might have mustered half a million additional Black troops, a staggeringly high number. How might this have contributed to the nation’s war effort? Sadly, we will never know.

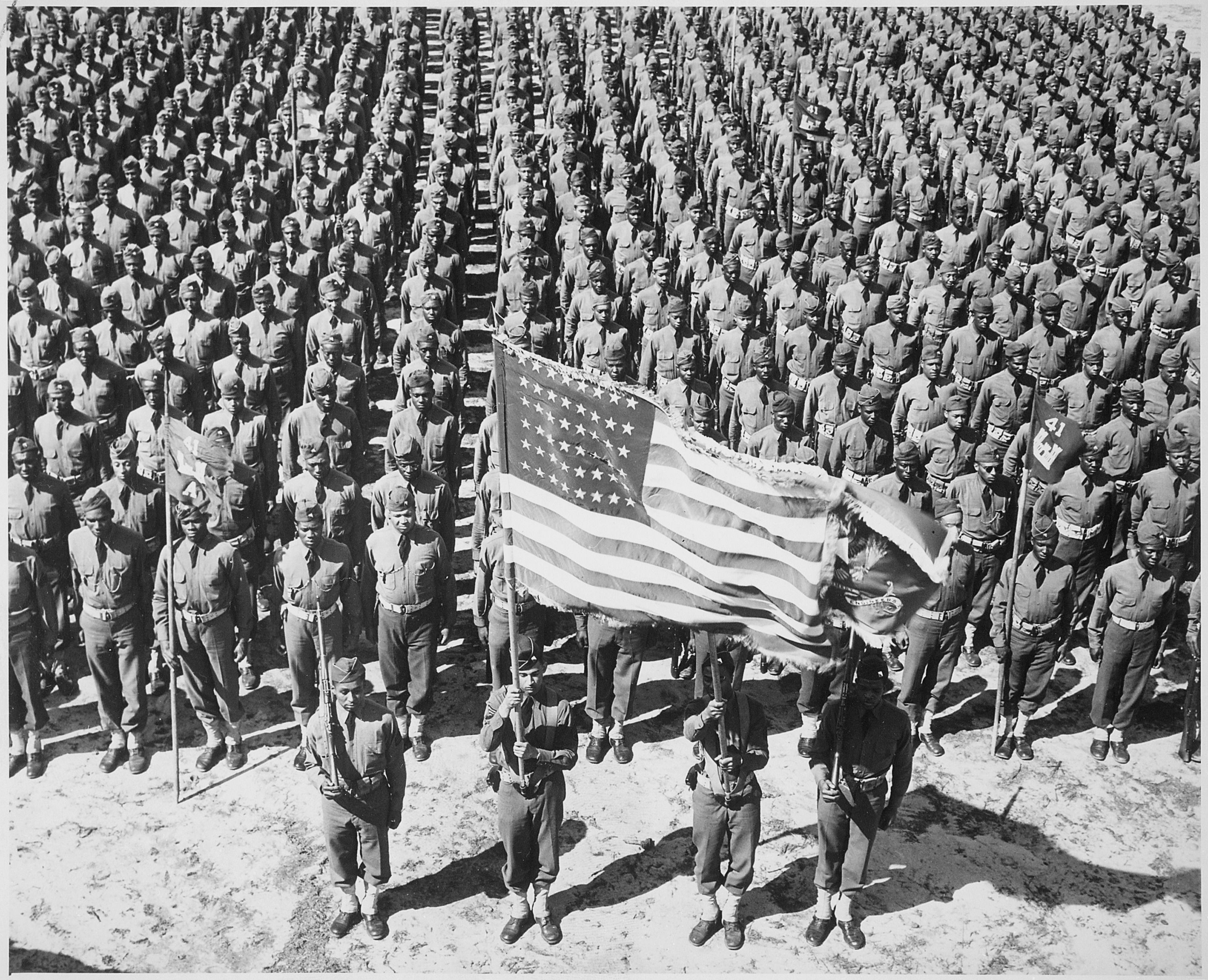

“On parade, the 41st Engineers at Ft. Bragg, NC in color guard ceremony," n.d. Courtesy of NARA, 208-NP-4HHH-2, NAID 535822.

Still, of the million or so Black GIs who gained entry in the military, “Jim Crow in uniform” met them at every turn. The military placed them in segregated units, whose enlisted personnel were solely Black and whose senior officers were solely White. It confined them, with few exceptions, to the least glamorous, least-skilled, and worst-paid jobs. It deprived them of promotions and positions of authority. It provided them separate and often unequal recreational facilities on and off posts, in the United States and all around the world. (That many of these posts were located in the Jim Crow South, where land was cheap and where powerful congressmen succeeded in attracting military investments, did not help matters.) It subjected them to a deeply discriminatory military justice system, which charged, sentenced, and executed disproportionately high numbers of them. It denied them the awards and honors and prestige they deserved. It delayed their demobilization at war’s end, compounding their disadvantages in the already discriminatory postwar job market. And it dishonorably discharged unfairly high numbers of them, denying them access to some life-altering GI Bill benefits. The list could go on.

Military leadership—from high command to officers in the field—built these color lines for one inescapable, if paradoxical, reason: In their view, winning the war for four freedoms required unfreedoms. In the case of the Black-White divide, leaders claimed repeatedly that the morale, efficiency, and discipline of US troops—by which they invariably meant White US troops—demanded it. The implication was that Whites would otherwise be too consumed by anti-Black resentments and conflict to invest their all in the war effort. The Black-White divide, from this perspective, was a wartime imperative, a precondition for victory. Many decades old, this line of argument was a damning admission about the depths of the nation’s anti-Black racism.

But, truthfully, the Black-White divide had more to do with leaders’ own sentiments—their widespread feelings and beliefs about Black people’s supposed inferiority as soldiers and as officers, and their deep, often taken-for-granted investments in White domination and Black subordination. Both, they seemed to believe in their bones, were natural, essential, and virtuous features of American life. Toward war’s end, this consensus showed cracks among some military leaders, especially in the navy, but also in the army, where its Research Branch’s effort to study and understand White and Black racial attitudes helped encourage reforms. But other military leaders clung tenaciously to Jim Crow in uniform, through victory and beyond.

“A good job in the air cleaner of an army truck, Fort Knox, Ky. This Negro soldier, who serves as truckdriver and mechanic, plays an important part in keeping army transport fleets in operation,” n.d. Courtesy of Library of Congress, digital ID fsac 1a35222.

Some ordinary White soldiers pushed back against their superiors’ racism, but the vast majority did not. In many cases, the military’s pervasive Black-White lines birthed or deepened White troops’ commitments to white supremacy, as several wartime opinion surveys showed, including those digitized on this website. White GIs expressed these commitments in a variety of ways, from refusing to salute Black officers to circulating the lie in France, Italy, India, and Australia that their Black comrades-in-arms, supposedly more monkey than man, had tails. Meanwhile, in rampant acts of racist terrorism, which occurred throughout the United States and around the world and involved anywhere from several soldiers to several thousand, Whites resorted to violence to enforce Black GIs’ subjugation.

All of this appalled many Black troops, of course, who were after all risking their lives to defend the United States—and doing so in the name of freedom, no less. It appalled their allies, as well, including Black newspapers, civil rights organizations, unions, religious groups, and troops’ families and loved ones. Together, both soldiers and their supporters built a sweeping protest movement in response, a precursor to and foundation for the more famous postwar civil rights struggles to come. Employing a range of tactics—from letters, petitions, editorials, political lobbying, voting, and litigation to boycotts, marches, strikes, sit-ins, and armed self-defense—they fought creatively and unwaveringly for “racial democracy in our armed forces.

The movement often came up against the most powerful forces in the US government—the White House, Congress, the courts, and the military—whether in the form of active hostility or detached indifference. And White public opinion, while it shifted somewhat in the war, remained firmly committed to Black subordination, in and out of the military. It is a testament to the movement’s power, then, that it nonetheless scored some victories during the war. It helped to integrate some training camp facilities, some military recreational spaces, and even some fighting units in Western Europe. More important still, it fundamentally shifted the conversation about military racism. For example, support for integrated military outfits was a fringe position at the start of the war, but a thoroughly mainstream one in liberal and left circles only a few short years later. Indeed, the postwar desegregation of the US military appears utterly inconceivable without appreciating African American GIs’ and their allies’ wartime activism.

Color Lines within Color Lines

Racism in America’s World War II military, however, involved more than Black and White people—even if we, scholars and non-scholars alike, forget this point sometimes. Even at the start of the war, one list of army inductees, organized by nativity, had eighty-three entries, including places as far-flung as Panama and Persia, Haiti and Hungary, Chile and China, Liberia and Latvia. The US military shoehorned this kaleidoscopic swath of humanity into a sometimes-shifting set of so-called racial categories, including, besides Negro and White, Japanese, Chinese, Puerto Rican, and American Indian. Sometimes the military’s ubiquitous Black-White lines counted anyone not Black—including Asian Americans, Latin Americans, and Native Americans—as White. One 1940 War Department memo regarding who would join White military outfits, for example, held that “[t]rainees of all races other than negro will be assigned the same as white trainees.”

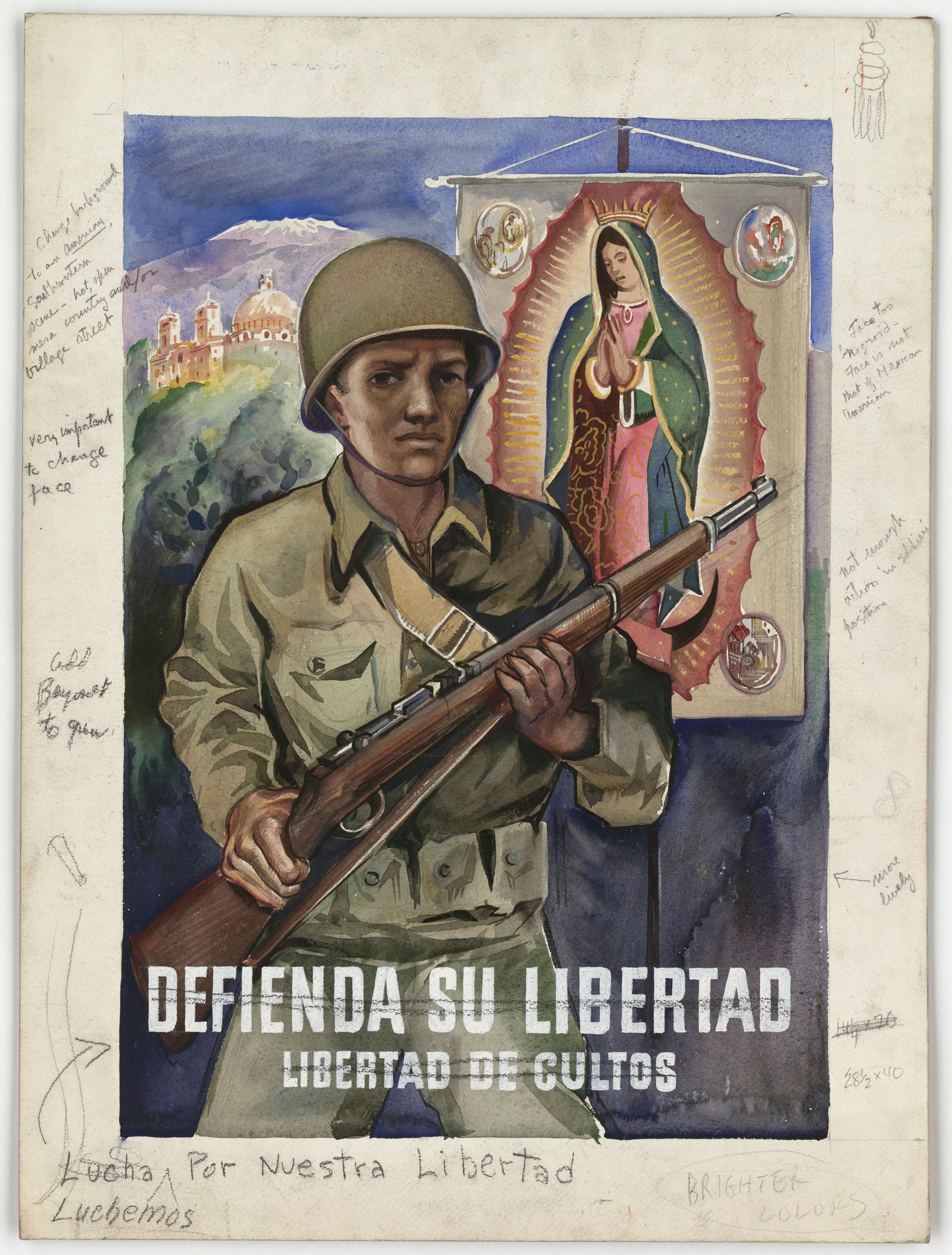

"Defienda Su Libertad—Libertad De Cultos” [Defend Your Freedom—Freedom of Worship], n.d. Artist [Xavier Gonzalez]. Top-right marginalia: “Face too Negroid - Face is not that of Mexican American." Courtesy of NARA, 208-AOP-100-99, NAID 7387527.

But these non-Black minorities also faced their own distinctive set of color lines. Never nearly as widespread or as powerful as Jim Crow in uniform, they nonetheless mattered, especially to those ensnared by them. Take the most extreme case of Japanese Americans. Given their supposed unbreakable ties to America’s archenemy in the Pacific, they were, for a time, completely barred from joining any part of the US military. Even after Japanese American activism helped convince the army—but no other branch—to resume their induction, the army did so with numerous strings attached: many Japanese Americans would be required to join segregated outfits; all would endure a singularly lavish level of surveillance and scrutiny; and some would face other day-to-day indignities, including harassment from fellow soldiers and barriers to promotion and to the senior officer ranks. Other non-Black minority groups, such as those of Chinese, Filipino, Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Native descent, encountered similar obstacles and more.

Blurred Lines & Aftermaths

Troops’ experiences of training and fighting could and did blur these various color lines at times. For many non-Black minorities in particular, their frequent ability to serve shoulder to shoulder with White troops led to new levels of camaraderie, friendship, and acceptance. “Finding ourselves in a new setting away from the old surroundings, with new faces, new friends, and everyone in the same boat,” recalled one Mexican American, “put us on an equal status.” Something similar happened with some Black troops as well, though far less frequently, due in large part to the wider reach of military anti-Black racism. Still, whether it was the friendliness of foreigners, a foxhole fraternalism that occasionally crossed even the Black-White divide, or African American GIs’ own ongoing activism, Jim Crow in uniform lay moderately wounded at war’s end. The military’s other racisms sustained even greater wartime injuries.

The call and response of World War II-era military racism and resistance ultimately cast a long and complex shadow over postwar American life. On the one hand, they convinced or further convinced a growing number of American veterans of all shades to democratize the nation, invigorating a range of existing freedom struggles and laying the foundation for important civil rights gains to come, beginning with the desegregation of the military itself. On the other hand, the military’s color lines also undermined these struggles and any hopes of building a more egalitarian nation. They traumatized an unknowable number of non-White troops, especially the Black people among them. They further naturalized the very idea of race and deepened many Whites’ commitments to white supremacy. And they further fractured the American people and their politics.

These are not the stories many of us typically associate with the Good War, the Greatest Generation, or the US military. But they do reflect a critical piece of millions of American soldiers’ World War II lives—and, as a consequence, their postwar days to come.

Thomas A. Guglielmo

George Washington University

Further Reading

Margarita Aragon, “‘A General Separation of Colored and White’: The WWII Riots, Military Segregation, and Racism(s) beyond the White/Nonwhite Binary,” Sociology of Race & Ethnicity 1, no. 4 (Oct. 2015): 503–16.

Takashi Fujitani, Race for Empire: Koreans as Japanese and Japanese as Americans during World War II (University of California Press, 2011).

Thomas A. Guglielmo, Divisions: A New History of Racism and Resistance in America's World War II Military (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Robert F. Jefferson, Fighting for Hope: African American Troops of the 93rd Infantry Division in World War II and Postwar America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008).

Ulysses Lee, The Employment of Negro Troops (GPO, 1963).

K. Scott Wong, Americans First: Chinese Americans and the Second World War II (Harvard University Press, 2005).

Select Surveys & Publications

S-32: Attitudes of and toward Negroes

S-144: Post-War Plans of Negro Soldiers

S-174: Negro Study

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 7 (July 1944)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 13 (April 1945)

Portions of this essay have been adapted from Thomas A. Guglielmo, Divisions: A New History of Racism and Resistance in America's World War II Military (Oxford University Press, 2021).

SUGGESTED CITATION: Guglielmo, Thomas A. “Race & Ethnicity.” The American Soldier in World War II. Edited by Edward J.K. Gitre. Virginia Tech, 2021. https://americansoldierww2.org/topics/race-and-ethnicity. Accessed [date].

COVER IMAGE: "...troops in Burma stop work briefly to read President Truman's Proclamation of Victory in Europe," 9 May 1945. Signal Corps Photographic Center, Army Pictorial Service, Office of the Chief Signal Officer, War Department. Courtesy of NARA, 111-SC-262229, NAID 531341.