About the Surveys & Data

In October 1941, the United States War Department created a Research Branch in the Morale Division of the US Army, the aim of which was to investigate soldiers’ morale, broadly defined. Over the next four years, this effort evolved into a multifaceted program of studies, more than two hundred in total, that covered subjects as diverse as leave policies, food preferences, radio listening, combat experiences, racial views, mental and physical health, postwar plans, and many others.

All the survey data known to have survived the war are available on this website.

Army Survey Program at a Glance

Surveys administered during the war: 200+

Servicemembers surveyed: 500,000+

In the collection

Number of surveys: 86

Study questionnaires: 158

Servicemembers represented: 304,909

Quantitative datasets with standard attitude items: 139

Number of questions: 15,756

Qualitative datasets with open-ended free responses: 67

Number of pages: 65,093

Studies with mixed (qualitative and qualitative) datasets: 19

Who was Surveyed?

The Research Branch conducted Planning Survey I, its first survey, at Fort Bragg, N.C., with a cross-section of enlisted personnel from the Ninth Infantry Division. Taking several days, the survey commenced December 8, 1941, the very day after Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor and other naval installations, adding to its significance in the eyes of the researchers in charge.

Postcard of the Officers’ Club at Fort Bragg, N.C., between 1938 and 1942. Postcard by: Allan Turlington’s Photo Shop, Fayetteville, N.C.. Courtesy of State Archives of North Carolina, Raleigh, N.C. Fort Bragg Postcard Collection, MMP 10.P138.

The existing data come from questionnaires filled out by soldiers, airmen, and female servicemembers on stateside bases and in theater overseas. Representing all branches of the army, respondents were selected using survey methods approximating random sampling. After receiving authorization from a post commander to conduct a survey, a small field research team started its work by consulting the personnel records of a particular organization and selecting every nth enlistee or officer (perhaps every eighth or ninth) according to that organization’s strength to create a representative cross-section.

Most early surveys were administered to all-White samples—defined broadly as not African American—yet starting in 1943, Black samples were drawn with more regularity. While nearly all respondents were men, there are three surviving surveys of women, two of nurses and one of enlisted women in the Women’s Army Corps. Only the quantitative standard attitude items still exist for these and not the free responses. Still, a number of men were asked for their opinions about WACs and other women in and out of service. Some groups of civilian employees were also surveyed, but the data are lost.

Survey 90: ATTITUDES TOWARDS WOMEN IN THE SERVICES

How were they surveyed?

Having created this pool of participants, the field team trained local service personnel as “class leaders” to conduct the survey in groups, or "classes," of 20 to 50 participants. Self-administered questionnaires that had already been field tested were almost always used. Ten such pretests are available on this website (e.g., S-86: Pretest Form). Respondents who were unable to complete a questionnaire independently were interviewed by a trained servicemember using the same form provided to other respondents.

This process was repeated at each post chosen as a survey site. Most studies, unlike the first, involved multiple military installations, with sample sizes ranging between 100 and 25,000. Not only were cross-sections created from particular units or organizations, but also of much larger elements of the army, indeed sometimes encompassing an entire force, designated by race, on a continent or in a theater. Studies late in the war, such as S-106, were carried out across the world.

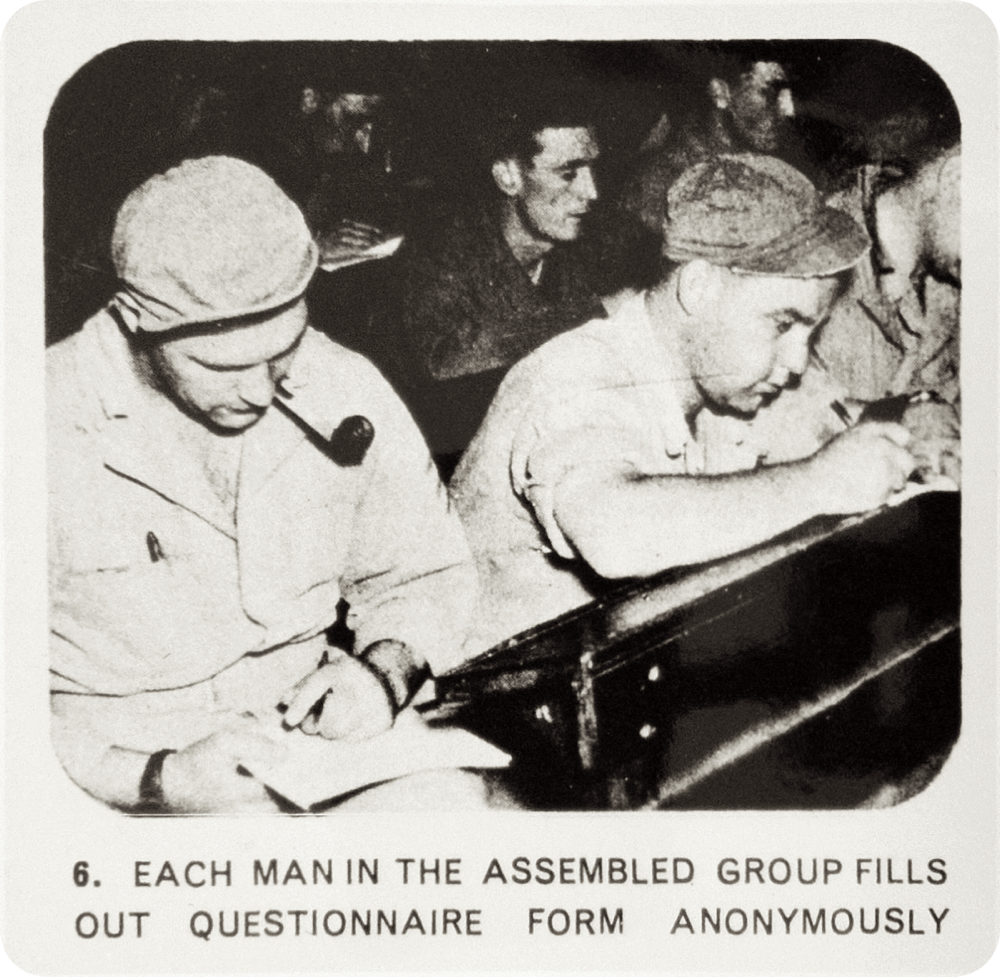

"Each Man in the Assembled Group Fills Out Questionnaire From Anonymously," Justification for Existence of the Research Division to Thursday Reports, box 970, RG 330, NARA, NND 813030, NAID 6926560.

Mess and recreation halls and base theaters served as typical survey sites. Improvisation was often necessary, however, particularly in overseas theaters. Once assembled, servicemembers who had been selected were assured of absolute anonymity to elicit their honest opinions. Strict protocols were followed after the administration of a survey so that no responses could be linked back to any one soldier.

Only in those instances in which a servicemember ignored instructions not to write their name or serial number on their paper questionnaire do we know their precise identity.

"You are going to be given some questions, and the same questions will be put to hundreds of other soldiers here in this Division. The questions are not personal; they simply ask you what you think about a lot of things that the War Department is interested in...

"[H]ere's your chance, a chance to say what is going right and what isn't... The War Department is really interested in finding out what the soldiers themselves think about the Army...

"[T]his kind of thing has never been done in this Army, or in any other Army in the world. It is being done for the first time right here in the 9th Division, and because of this we are asking you to help, and to answer these questions just as carefully as you possibly can..."

— Instructions given by class leaders to enlistees before taking Planning Survey I. Similar instructions were provided to respondents in surveys that followed.

What was asked?

Although the surveys were anonymous, questionnaires quite often opened with a standard set of questions to elicit basic information about the respondent. When demographic data are available, not only will they appear on this website among the standard items, but also as refinement filters. These include:

When a survey on this site asked for personal information, a "Refine Results" button will appear under a question that allows question responses to be filtered by these attributes.

- age

- branch of service

- children or children (expecting)

- drafted or volunteered

- education

- length of service

- marital status

- camp or unit

- outfit

- rank

- region

- size of civilian residence

- state of civilian residence

Servicemembers were asked about their general adjustment to army life—indicated, for instance, by their satisfaction with job placement, training, and opportunities—as well about other markers of low or high morale, such esprit de corps. Most studies, though, were organized around specific themes or issues of concern to the organization itself. Attitude research was to help in policy formation, program planning, the provisioning of services, and dissemination of information. Army commanders could request tailored studies prior to D-Day of morale and mental preparedness for combat in line companies, in preparation for the invasion, although without reporting results at the subunit level to protect the privacy of individual soldiers.

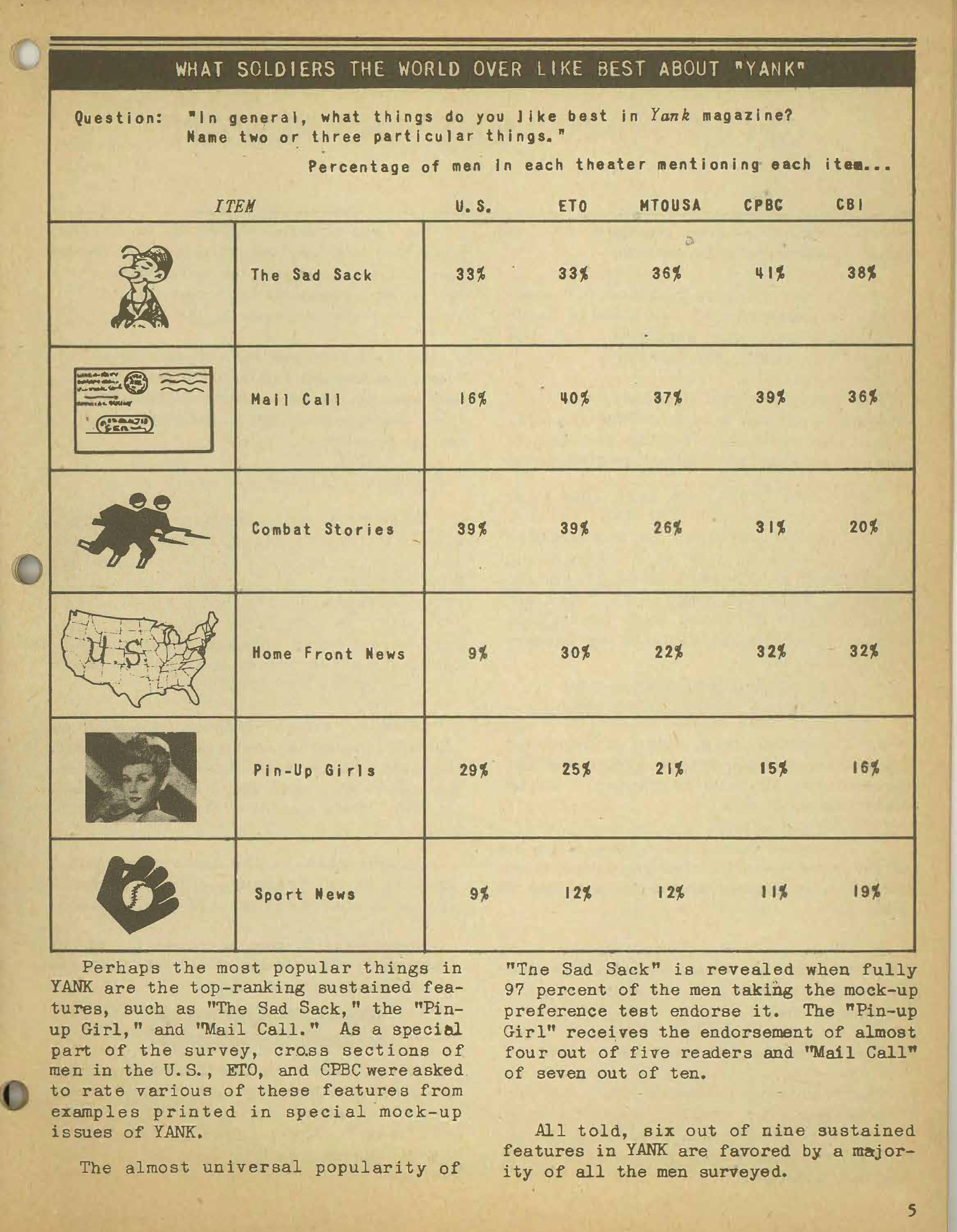

The results of preference surveys were passed on to editorial, programing, and production staffs to refine and improve broadcast schedules, the columns and features appearing in army periodicals, training and orientation films, and in other media and entertainment provisions. The June 1945 issue of What the Soldier Thinks reported that the Sgt George Baker's "The Sad Sack" cartoons were enjoyed by troops world round.

Many of the surveys were requested by the Morale Division and by Special Services, the parent agencies of the Research Branch within the army's organizational structure. These might be akin to the sort of consumer preference studies that a market research agency might conduct. Soldiers were asked what they listened to on the radio and when they listened; what kinds of books and magazines they read; what kind of games and sports they liked to play; and what correspondence courses they would be interested in taking; among numerous other inquiries about preferred leisure-time activities and educational opportunities.

Some studies were, however, broader omnibus surveys, covering a range of topics at one time. Similarly, some topics and concerns of ongoing interest to the War Department, such as demobilization and postwar planning, appeared in numerous surveys, sometimes as a question or two or a small series of questions. For example, the Research Branch worked closely with the Surgeon General’s Office to develop a diagnostic tool for identifying soldiers susceptible to “combat fatigue” and repeated in various studies a short list of questions designed to measure neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Tags that appear at the bottom of survey summaries are derived from keywords or "problem areas" noted in Research Branch documentation. The summaries themselves may include other relevant topics not captured by these tags. The essays located in Topics also are useful for identifying the broad range of subjects covered by Research Branch studies.

How the Data Was Used

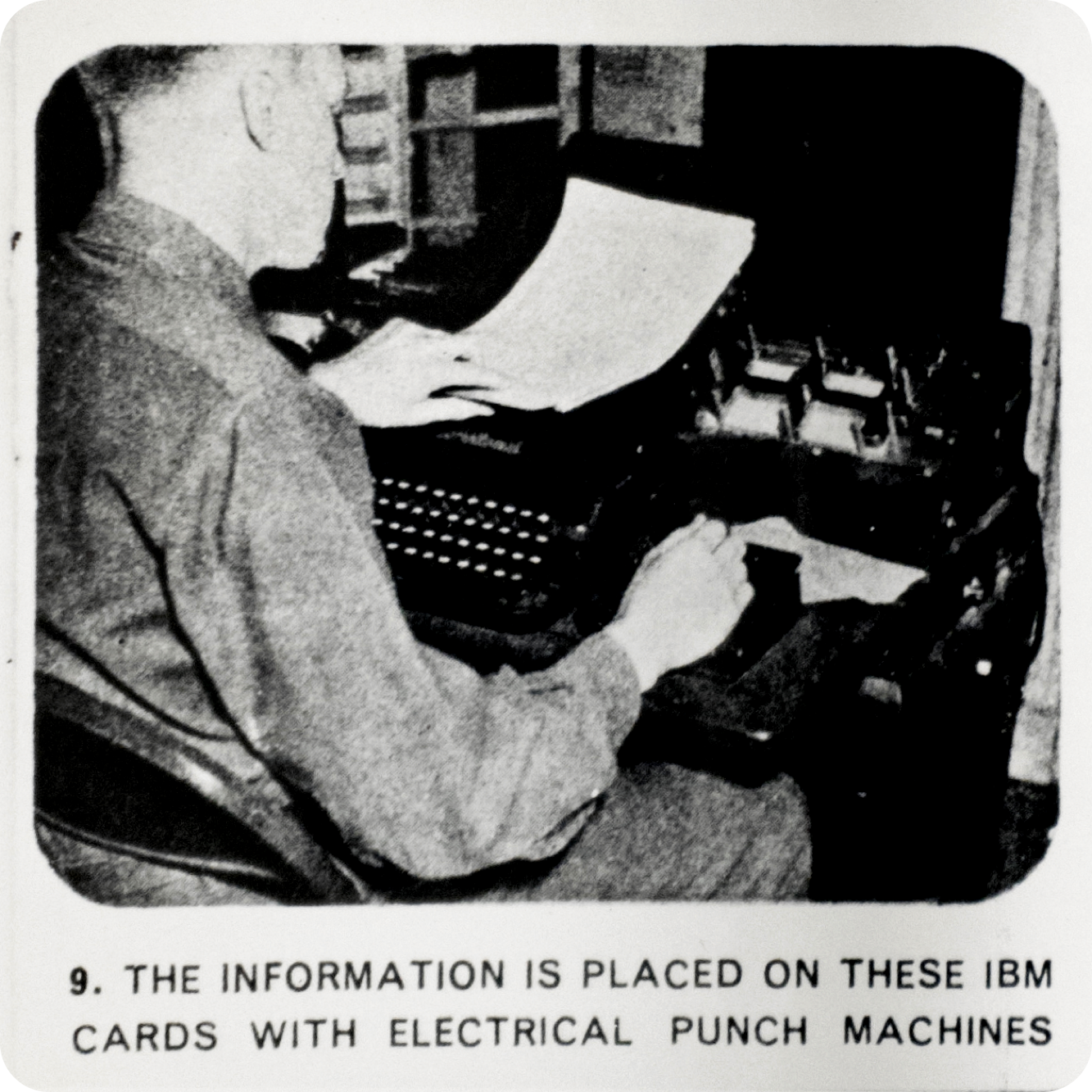

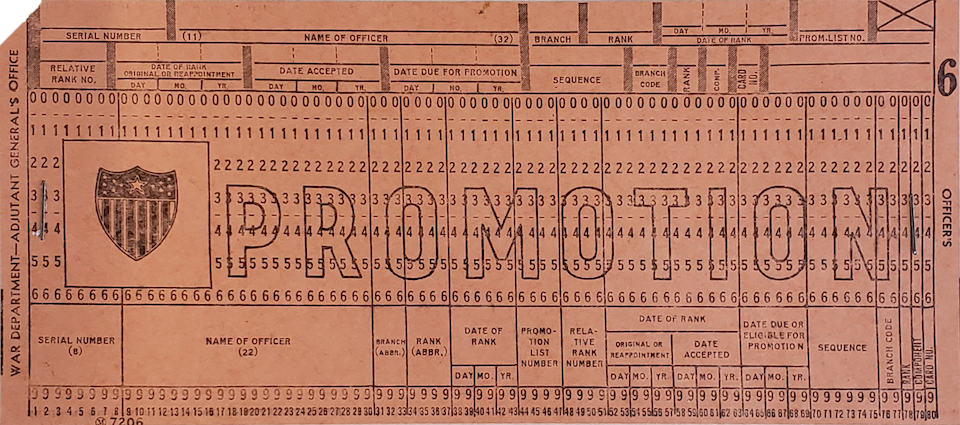

Completed questionnaires were shipped back to Washington, D.C. or in overseas theaters to headquarters behind the lines for processing, with a numerical value assigned to every response survey participants offered, including "free comments," which were read, sorted, and classified with open-ended commentaries sharing similar sentiments. Clerks operating IBM card punch machines transferred the resulting quantitative data onto 80-column cards for machine tabulation and statistical analysis, with a single respondent’s data requiring at least one card and typically more. Only sporadically, it seems, were complete free responses transcribed.

"The Information Is Placed on These IBM Cards with Electrical Punch Machines"

No sampled unit was ever to know the specific results from their unit. Reports and memoranda the Research Branch prepared after tabulating and analyzing survey data were generally restricted to the initiating agencies and to command. Statistics, often accompanied by illustrative free responses, were reported back to troops in issues of What the Soldier Thinks—after careful vetting.

Troops may have been unaware, but the answers they provided did influence War Department and army policies and operations, including:

- The introduction of Expert and Combat Infantryman Badges to bolster morale and increase the prestige of the infantry.

- The mental health screening of inductees using a Neuropsychiatric Screening Adjunct to identify those in need of psychiatric evaluation.

- The discharging of soldiers according to their "point score," based on factors that servicemembers recommended themselves, such as length of service, time overseas, parenthood, and combat experience.

- The desegregation of the US armed forces in 1948.

How the Data was preserved

By war’s end, the army was in possession of an estimated one million IBM punch cards of survey data. Most, if not all, would have been destroyed along with other war records deemed non-essential or of no historical value were it not for the forethought of the Research Branch’s leadership. During decommissioning, they secured authorization to have cards from many studies copied for reprocessing and reanalysis in anticipation of producing an authoritative account of the Research Branch's wartime efforts, The American Soldier four volumes.

The majority of cards went with the chief of the branch’s professional staff Samuel Stouffer to Harvard, while data from more experimental studies were shipped to Carl Hovland, the branch’s lead psychologist, at Yale. What became of Hovland’s collection is unknown, but after Stouffer died in 1960, his cards were donated to the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, then at Williams College and now at Cornell University.

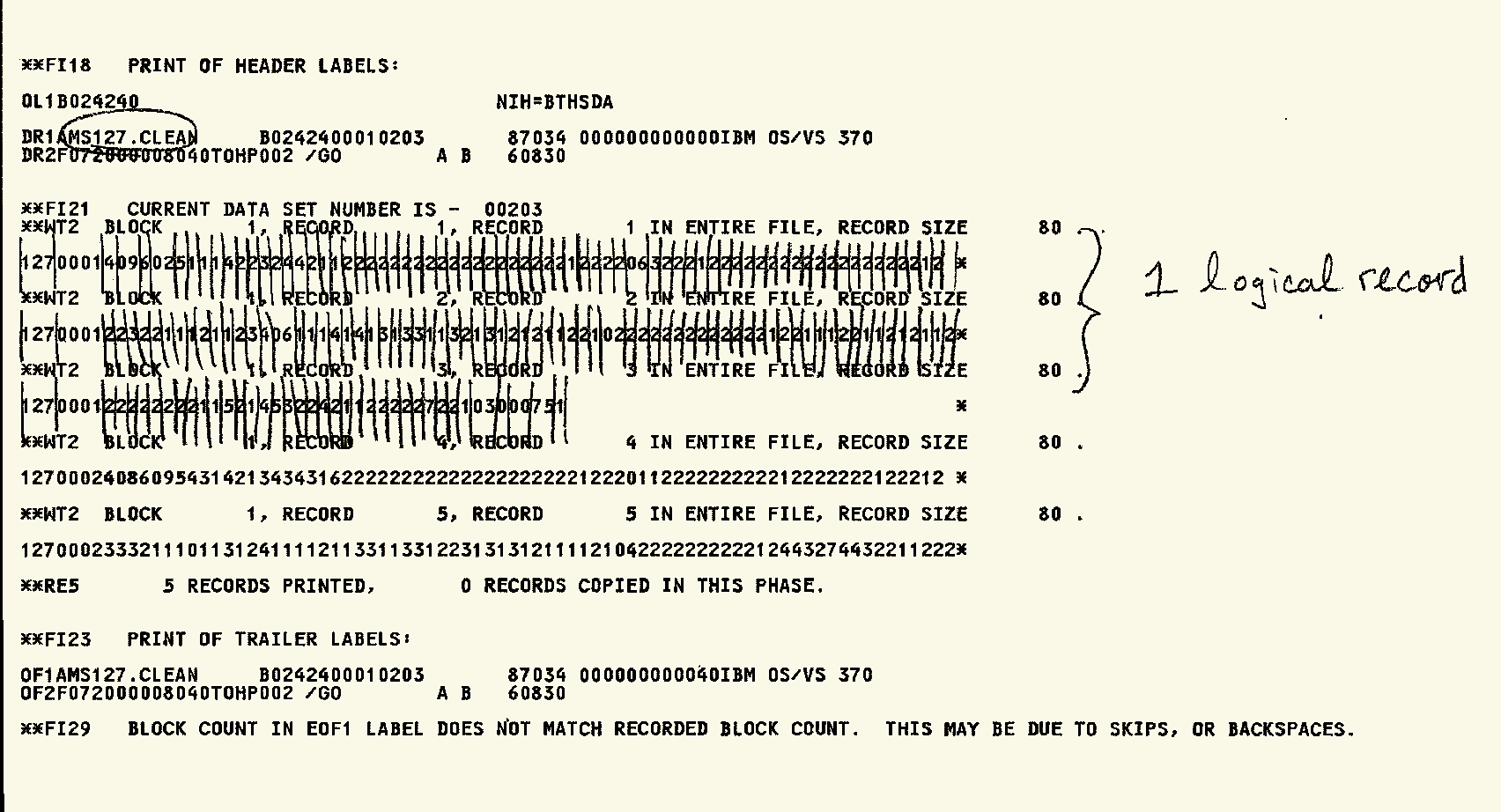

The discovery a dozen years later of a box left behind at Harvard happened to coincide with the establishment of the US Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, as a revived Research Branch. After learning of the existence of these lost records, ARI, as the institute is now known, contracted Roper to read all of the extant data to computer tape. At a later date, the National Archives (NARA), which received copies of the tapes, transferred their datasets to plain-text ASCII-formatted computer files, as did Roper.

NARA's record of the transfer of survey data from computer tape to ASCII-formatted computer files.

Other records associated with the army’s research program were deposited at NARA, yet the paper questionnaires were destroyed. Archival records indicate that psychiatric studies not accounted for among the copied punch cards were likely saved. Their status is unknown.

The Free Responses

In 1947, the War Department microfilmed the approximately 65,000 pages of handwritten free responses from a selection of studies. The 44-reel collection was transferred to NARA after being photographed along with the other manuscripts and documents. No copy of the collection is known to exist, and until this website was launched, the handwritten free responses could only be read by visiting the microfilm reading room at the National Archives.

To learn more about the transformation of these historic records, see Project History & Objectives. Also, more detailed information about the datasets and how to understand and interpret downloadable files is available in our page on How to Work With the Data.

COVER IMAGE: Research Branch, Information and Education Services, US Army; and TSFET, “Soldier Opinion: The Soldier’s Voice in a Modern Army,” 1945.