Ground Combat

Ground combat in World War II featured physical and psychological elements common to war since the ancient world, such as physical exertion, stress, confusion, discomfort, fatigue, hunger, boredom, homesickness, loneliness, group bonding, courage, and fear. These enduring realities were overlain with the impact of new technologies largely introduced before and during World War I and upgraded during the Interwar period, such as armored vehicles, mobile breech loading artillery, and an array of automatic weapons that gave enormous firepower to soldiers. Beyond these factors, the American way of war featured the ability to project power across vast distances. Logistics and transportation were strong suits of the American armed forces; no other ground force in World War II was as mobile or as well supplied. Although plenty of American GIs marched to war between 1941 and 1945, the percentage of the force that rode in wheeled or tracked vehicles was greater than that of any other army in history to that point.

Organizing the Army of the United States

The Army of the United States (AUS) was composed of the Regular Army, the National Guard, and the Organized Reserve, along with newly created “draftee” divisions. A small percentage of American GIs began their service as members of the small Regular Army (189,000 soldiers, including 15,000 officers, at the beginning of World War II), which played an outsized role in providing cadres to form new units once wartime mobilization began after the fall of France in the summer of 1940. President Franklin D. Roosevelt called the National Guard to federal service that fall, more than doubling the size of the army by adding 300,000 soldiers (including 19,000 officers) to active-duty rolls. The Officer Reserve Corps, the product of ROTC training at the nation’s land grant colleges, added 180,000 officers to the rolls, while the War Department commissioned another 100,000 officers (mostly specialists) directly from civilian life. But most of the nearly six million soldiers who served in the ground forces of the AUS arrived via the Selective Service Act, enacted on September 16, 1940, as the first peacetime draft in American history. The army selected from this pool 300,000 officer candidates, who received their commissions after attending newly created officer candidate schools. The AUS thus reflected the democratic nature of American society, with officer-enlisted relations much less rigid than in other military establishments of the era.

Most soldiers who entered service from 1940 to 1942 received their basic training in newly formed units, with a selected cadre of officers and noncommissioned officers supervising their individual and collective training. Once divisions passed their certification tests, they would often take part in army-level maneuvers in vast areas in the Carolinas, Tennessee, and Louisiana. Some units would receive specialized training: desert warfare at the Desert Training Center in southern California, Arizona, and Nevada; mountaineering skills at Camp Hale, Colorado; armor training at Fort Knox, Kentucky; airborne training at Fort Benning, Georgia; and tank destroyer training at Camp Hood, Texas. Units slated to participate in amphibious operations conducted rehearsals in the United States or at overseas locations before sailing for hostile shores.

Equipment

GIs would deploy overseas with newly designed and produced equipment: some excellent models, and some that were at a significant disadvantage to German (but not Italian or Japanese) counterparts. Perhaps the best weapon was the M1 Garand, a semiautomatic rifle with an eight-round magazine, introduced into service in 1937. Infantry would rely on Browning machine guns designed in the Interwar period (.30 caliber M1919 and .50 caliber M2), as well as the Browning automatic rifle, first introduced to service in 1918. Outgunned but reliable M3 Grant and M4 Sherman tanks, along with M10 Wolverine, M18 Hellcat, and M36 Jackson tank destroyers largely received less than flattering “Bronx cheers” from their crews. The real war-winner, though, was American artillery; the most common pieces were the M2A1 and M3 105mm howitzer, the M1 8-inch howitzer, and the M1A1 and M2 155mm “Long Tom” field guns. Making the AUS mobile were excellent “deuce and a half” and five-ton trucks, as well as the iconic and beloved quarter-ton, four-wheel drive “Jeep.” For troops engaged in amphibious invasions, most would swim ashore aboard Higgins boats—Landing Craft Vehicle and Personnel, or LCVPs.

"Sherman tanks, manned by French armored troops, roll down an LCT ramp onto a Normandy beach. This French fighting unit will take part in the liberation of their native land," 2 August 1944. Courtesy of NARA, 111-SC-199797, NAID 176888252.

Personnel

Keeping combat units effective once deployed overseas was a difficult task. To keep the arsenal of democracy functioning and to man the US Navy, US Army Air Forces, Coast Guard, and Marines, the War Department decided to cap the number of ground divisions at 89. This so-called “90-Division Gamble” meant troops remained in combat far longer than desirable, with little chance of relief aside from a “million dollar” wound or the end of the war. The Mediterranean and European theaters differed in this regard from the Pacific theaters; in the campaigns for Italy, France, and Germany, troops remained more or less engaged for the duration, while in the Southwest, South, and Central Pacific theaters, the episodic nature of island hopping often limited long-term exposure to combat. Troops left in contact with the enemy for prolonged periods suffered from higher rates of "battle fatigue" (similar to post-traumatic stress disorder in current terminology). Surveys indicate the lack of a rotation policy as the single most important issue for troops in combat units. On the other hand, the data also indicates that soldiers in divisions with a long history of wartime service had a great deal of pride in them.

At the tip of the spear, rifle companies were especially prone to high turnover due to battle casualties and disease. Only a fraction of the soldiers who entered combat with a rifle company were still serving in that same unit at the end of the war, a situation especially applicable to junior officers. To keep units up to strength, the War Department resorted to an individual replacement system. A little more than a third of soldiers began their service as replacements. Soldiers trained for thirteen weeks in one of twenty-one replacement training centers located across the United States before heading overseas, where they remained in replacement depots, or “repple depples” in GI slang, until needed. Soldiers’ training deteriorated as they awaited assignment, while their life expectancy in combat varied based on the reception they received in their units and whether they joined up at or behind the front lines. The system had many flaws, but it was the correct choice given the limitations of the 90-Division Gamble. Once committed to combat, most divisions eventually developed into combat-effective organizations. Enemy action destroyed only two: the Philippine Division on Bataan in 1942, and the 106th Infantry Division, which saw two of its regiments surrender during the opening stages of the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944.

Combat Experience

The experience of soldiers in combat differed greatly depending on where they served and fought. More than 12,000 American soldiers fought in the rugged terrain of the Bataan Peninsula and on Corregidor Island in the Philippines and endured more than three years of brutal captivity when they surrendered to the Japanese in April and May 1942. On the other side of the world, the first taste of combat for the AUS came on the beaches of Morocco and Algeria, followed by difficult fighting in the desert and mountains of Tunisia. There the Germans inflicted a sharp defeat on American troops at the Battle of Kasserine Pass, but US leaders and soldiers learned from their mistakes and improved their combat effectiveness in the fighting for Bizerte and Tunis, experience that would serve them well in follow-on campaigns in Sicily and Italy.

"Moving up through Prato, Italy, men of the 370th Infantry Regiment have yet to climb the mountain which lies ahead," 9 April 1945. Courtesy of NARA, 111-SC-205289, NAID 531277.

Beginning in the fall of 1943, US units in Italy faced German forces dug into an unrelenting series of mountain fortifications, the most imposing of which were the Gustav Line, anchored on Monte Cassino, and the Gothic Line in the Apennine Mountains. Troops fought in terrain so rugged they had to use mules to supply themselves in some cases. The only unit specifically trained for these conditions, the Tenth Mountain Division, performed heroically in seizing Riva Ridge, Monte Belvedere, and the high ground in the Apennines leading to the Po River Valley, which Allied forces seized in April 1945. The Italian campaign also featured the crucible of the Anzio beachhead, which came closer to resembling the trench warfare of World War I than any other fighting in which the AUS participated.

The most iconic battles for the AUS came on and after D-Day on June 6, 1944. Although nearly 3,500 soldiers gave their lives to secure the beaches of Normandy—most of them in the carnage on Omaha Beach—far more would succumb to fighting in the bocage, the hedgerow country of the Cotentin Peninsula. After seven weeks of attritional fighting, the First and Third US Armies broke out of the lodgment area, defeated German forces at the Battle of the Falaise Gap, and pursued retreating German forces across France. US and French forces invaded southern France on August 15, adding more weight to the Allied juggernaut. US armored divisions finally entered the war in force during the breakout from Normandy and pursuit across France, and performed well despite the limitations of the M4 Sherman tank, which could not compete one-on-one with newer German models, especially the heavily armored Panther and Tiger tanks with their long-barreled 75mm and 88mm main cannon.

"Down the ramp of a Coast Guard Landing barge Yankee soldiers storm toward the beach-sweeping fire of Nazi defenders in the D-Day Invasion of the French Coast. Troops ahead may be seen lying flat under the deadly machine gun resistance of the Germans. Soon the Nazis were driven back under the overwhelming Invasion forces thrown in from Coast Guard and Navy amphibious craft," 7 June 1944. Courtesy of NARA, War and Conflict Number 1041, NAID 513173.

Veteran combat infantryman, 5307th National Regiment (Merrill’s Marauders), China-Burma-India Area

Combat in the Pacific theaters created different challenges for American soldiers. Operations in the malarial jungle of the islands of the Southwest Pacific led to more non-combat casualties from disease than from combat action against the Japanese. Elsewhere, army regiments and divisions fought in conjunction with the US Navy and Marines to island hop across the Central Pacific, learning how to take heavily fortified atolls and destroy Japanese troops fighting to the death in bunkers and caves. Until the invasion of Luzon in January 1945, combat in the Pacific was episodic, with short periods of fighting interspersed with longer periods of regeneration, training, and planning for upcoming operations. The immature base structure and rugged geography of the islands in the Pacific, however, meant that troops faced long periods of boredom and limited training opportunities when not in combat, leading to deterioration in their morale and physical conditioning.

"165th Infantry assault wave attacking Butaritari, Yellow Beach Two, find it slow going in the coral bottom waters. Japanese machine gun fire from the right flank makes it more difficult for them. Makin Atoll, Gilbert Islands," 20 November 1943. Courtesy of NARA, 111-SC-183574, NAID 531172.

The heady days of the liberation of Paris and the pursuit across France and the Low Countries came to an end at the West Wall fortifications along the German border, where limited supplies temporarily halted the advance and an autumn of rain, cold, and mud ensued. Fighting along the borders of the Third Reich included combat in wooded and mountainous areas, highlighted by the ill-conceived Battle of the Hürtgen Forest and the titanic Battle of the Bulge—the largest battle in the history of the US Army. US forces also crossed numerous rivers as they fought to enter the heart of Germany, most notably the Rhine River, breached in an assault crossing at Oppenheim by Lieutenant General George S. Patton’s Third US Army and by the seizure of the intact railroad bridge at Remagen in the First US Army zone.

Terrain and Weather

Wherever they served, American soldiers braved the elements: rain, snow, cold, heat, humidity, dust, and mud. The First Cavalry Division complained of “an enemy that all through the Leyte Campaign caused more trouble and difficulty than the Japanese ever did. It was mud, and rain, and mud, and typhoons, and mud, mud, mud.”1 In Europe, the winter of 1944-1945 was one of the coldest in recorded history, and troops out in the elements suffered from hypothermia, trench foot, and frostbite. In the Pacific, the heat and humidity of Guadalcanal, New Guinea, and other islands led to jungle rot and other tropical maladies. US troops also experienced their share of urban combat in World War II. In Northwest Europe, army troops fought bitter battles for Brest and Aachen, while in the Pacific the horrible carnage of the Battle of Manila foreshadowed what awaited US troops in the Japanese home islands. Fortunately for those soldiers, Japanese surrender after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki made the invasion unnecessary.

"Combat Men's Winter Clothing Preferences," What the Soldier Thinks, no. 13 (April 1945).

Logistics

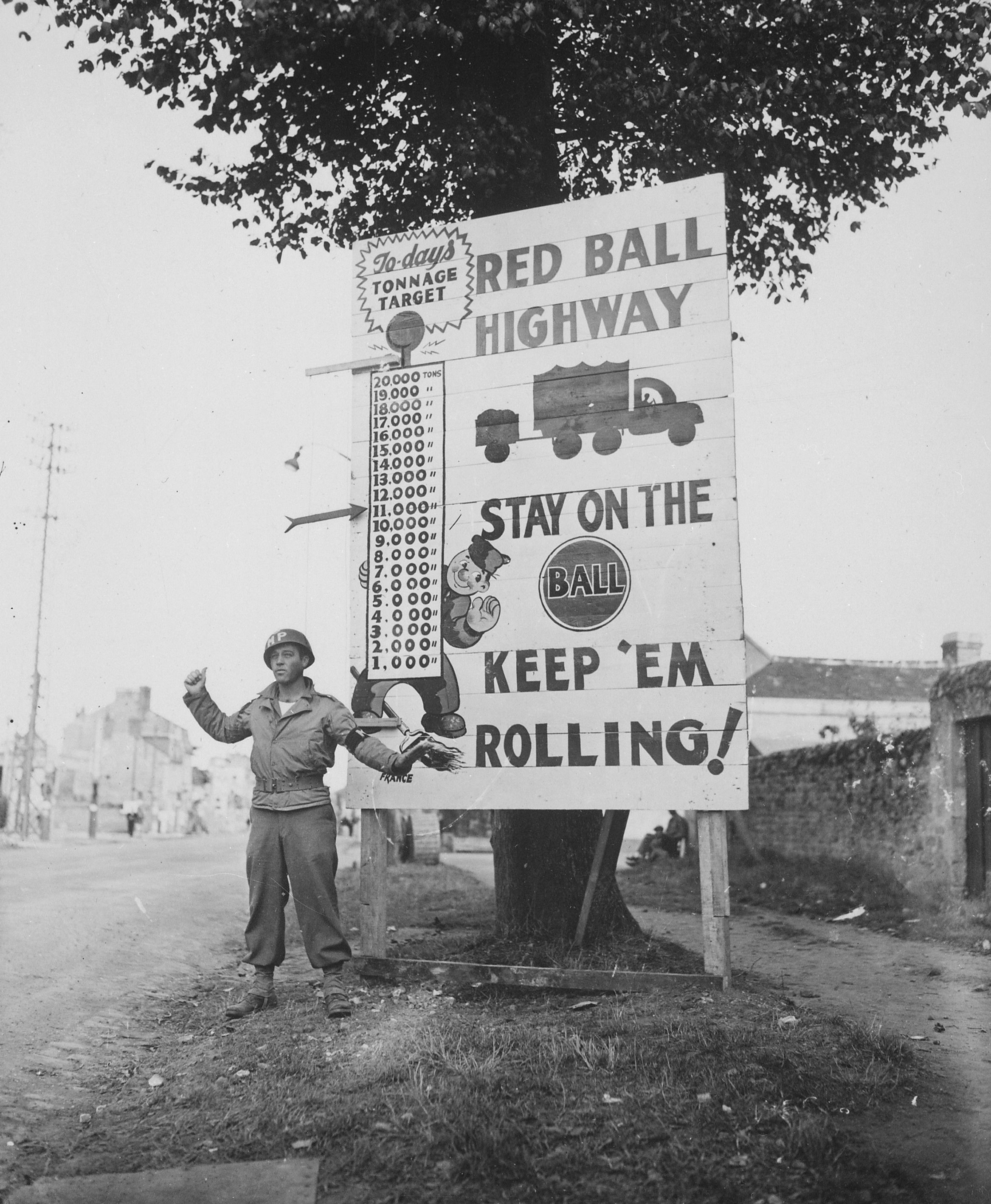

Focus on ground combat should not obscure the fact that less than half of soldiers in the AUS served in units at the “front.” Most—perhaps as many as two-thirds—served in combat support organizations or in the enormous logistical establishments in “rear” areas. After the breakout from Normandy, for instance, US commanders dedicated more than 6,000 trucks—75 percent of them crewed by Black soldiers—to the “Red Ball Express,” a system of loop roads designed to expedite the delivery of supplies from the beaches of Normandy to the First and Third US Armies racing across France. On the other side of the world, every American soldier in the Pacific War was supported daily by four tons of supplies; every Japanese soldier by a mere two pounds.

"Corporal Charles H. Johnson of the 783rd Military Police Battalion, waves on a 'Red Ball Express' motor convoy rushing priority materiel to the forward areas, near Alenon, France," 5 September 1944. Courtesy of NARA, 111-SC-195512, NAID 531220.

Due to the heavy weighting of the “tail” of combat service support establishments, the AUS was far more lethal than its adversaries. The use of Black soldiers primarily in combat service support units was not by accident, as senior army leaders were reticent to employ Black soldiers in combat. The AUS formed two divisions of “Buffalo Soldiers” during the war: the 92nd Infantry Division, which engaged in combat in the Italian campaign, and the 93rd Infantry Division, which saw limited duty in the Pacific. Of more importance, calls for Black volunteers to form infantry platoons to augment the strength of White companies during the Battle of the Bulge met with an overwhelming response, and the honorable conduct of these soldiers helped pave the way for the integration of the armed forces after the war.

As the surveys and associated comments show, the experiences of US soldiers fighting in ground combat in World War II displayed similarities associated with the universal nature of war and differences attributable to the characteristics of combat in particular theaters. Most soldiers had two overriding goals, however: to survive and to finish the job and return home to their loved ones.

Peter R. Mansoor

Ohio State University

Further Reading

Eric Bergerud, Touched With Fire: The Land War in the South Pacific (Viking Penguin, 1996).

John Sloan Brown, Draftee Division (University Press of Kentucky, 1986).

Lee Kennett, G.I.: The American Soldier in World War II (Scribner, 1987).

Peter Mansoor, The GI Offensive in Europe (University Press of Kansas, 1999).

John McManus, The Deadly Brotherhood: The American Combat Soldier in World War II (Presidio, 1998).

Peter Schrijvers, Bloody Pacific: American Soldiers at War with Japan (Palgrave MacMillan, 2010).

Robert Rush, Hell in Hurtgen Forest: The Ordeal and Triumph of an American Infantry Regiment (University Press of Kansas, 2001).

Select Surveys & Publications

S-91: Survey of Combat Troops in England

S-100: Attitudes of Combat Infantrymen

S-101: Attitudes of Combat Infantry Officers

S-106: Post-War Army Plans (Officers and EM)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 2 (January 1944)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 5 (April 1944)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 9 (September 1944)

The American Soldier (1949), vol. II

- Bertram C. Wright, The 1st Cavalry Division in World War II (Tokyo, 1947), 75.

SUGGESTED CITATION: Mansoor, Peter R. “Ground Combat.” The American Soldier in World War II. Edited by Edward J.K. Gitre. Virginia Tech, 2021. https://americansoldierww2.org/topics/ground-combat. Accessed [date].

COVER IMAGE: "Fox Holes: Dig!.. or Die!" Newsmap 2, no. 1 (26 April 1943). Army Orientation Course, Special Service Division, Army Service Forces, War Department. Courtesy of NARA, 26-NM-2-1b, NAID 66395123.