Discipline & Military Justice

The story of the war for most Americans today is one of glory, purpose, and rare moral clarity. In this story, we see civilians going from green, sloppy recruits to hardened, disciplined veterans motivated by zealous belief in a righteous cause. But the archival record reveals a different story when it comes to discipline and justice. The citizen-soldier of World War II rarely felt the esprit de corps once used to motivate militaries from the Napoleonic armies to the World War I forces that clashed in Flanders. Enlisted personnel in World War II tended to reject the idea that they ought to submit themselves to strict obedience and order. They instead fought for the men in their unit and for the chance to get away from the world of military rank and rules when they next hit port.

On the home front and abroad, the US Army struggled to maintain discipline and adequately administer justice. These failures led to recurring civil-military conflict, tensions between occupiers and occupied, and racial injustice. While the army established a wide legal purview to prevent civil authorities from prosecuting their men, they also proved unable and sometimes unwilling to stop White troops from committing crimes like becoming drunk and disorderly, assaulting women, stealing vehicles, and brawling with civilians and other servicemen. Each military branch ultimately declared that civil legal authorities and foreign courts had no ability to hold or charge their men, and this appropriation of legal power allowed the army to further seize policing and control of urban centers. In cities like Chongqing, San Francisco, Colón, and Le Havre, soldiers discovered the incredible legal privileges afforded by their uniforms while taking liberty.

“The Corps of Military Police,” Newsmap 3, no. 44 (19 February 1945). Courtesy of NARA, 26-NM-3-44b, NAID 66395302.

Training & Chickenshit

The US Army and the average draftee were wholly unprepared for war in 1941, leading to initially poor training and recurring morale issues. Years of inadequate funding and training left the branch unable to field a modern, technically skilled force capable of handling antiaircraft gunnery, communications, logistics, mortars, and tanks. Bases and training camps were often either dilapidated or existed as little more than a blueprint. The men of the “Old Army”—the regulars who stayed in the service through the interwar years—harassed and bullied the “number men” (i.e., men who were drafted). Arriving in half-constructed camps, draftees stumbled through mud-clogged streets or braced themselves against the wind flinging dust and grit through the air. Observers recalled the young men walking like frightened calves as they made their way to barracks that stunk of wood smoke and rattled with each gust. In their cots, they tried to sleep knowing they had left the civilian world.

Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall and other planners initially envisioned that the millions of draftees would embrace army discipline out of a sense of patriotic duty. This esprit de corps model was borrowed from the World War I American Expeditionary Force, who were spurred to enlist to defend the country and, if they were first- or second-generation immigrants, prove their loyalty and citizenship. Marshall promised that the army would soon instill an “American standard of discipline” that he defined as “cheerful and understanding subordination of the individual to the good of the team.” The army stressed values of faith, duty, obedience, and surrendering personal desires to the larger war effort.

Soldiers immediately saw the contradiction of joining an organization based on obedience and rank to defend freedom and democracy. In the barracks, men railed against cruel punishments and “sadism thinly disguised as necessary discipline,” condensing all these privations into the term “chickenshit.” To enforce deference and control, officers might make their men dig a trench for a latrine when the camp already had a functioning system—a typical example of chickenshit. An army-commissioned study discovered that the draftees were rebelling against these attempts to remake civilians into zealous, adept soldiers.1 The study’s authors recorded troops failing to salute their officers, mocking leadership, and even physically threatening commanders. The old model of building discipline nearly buckled as officers saw the enlisted men become insubordinate and near mutinous. One draftee openly told TIME magazine, “To hell with Roosevelt and Marshall and the Army and especially this Goddamn hole.”

With morale and discipline falling, the army brass chose to lessen their reliance on the old model of indoctrination that emphasized faith in the cause, duty, and pride in one’s unit. Instead, the force took up a more organic vision of soldiering centered on swaggering, aggressive, heterosexual masculinity that contrasted rugged military service with an effeminate and disgraceful civilian world. As most enlisted men would never see combat, getting drunk and aggressively approaching women, or beating up the guy not in uniform, became a way to mark oneself as a true military man. Army sociologists identified this “barracks culture” as the place where men began to identify with military life, building discipline and a commitment to their unit.

Hitting Port

When troops completed training, they were sent on trains to stopover cities like Chicago and on to major US ports like New York City for additional training or to support logistical operations. Up to 75 percent of the army’s manpower was stationed stateside until immediate preparations for D-Day began in 1944, and 25 percent of troops never left the country at all. Thus, many soldiers saw several US cities before shipping abroad either for operations or leave and furloughs. Men coveted these opportunities to escape the constant supervision of their superiors and see teeming metropolises that promised to ply them with alcohol, sex, and other entertainments. Troops swarmed fun zones like New York’s Times Square and Coney Island, while sailors in Boston filled up Scollay Square. Women were warned by civil authorities to avoid these areas, and MPs and municipal cops did little to stop street harassment and outright assaults. When troops went abroad, similar patterns emerged where servicemen could treat civilians with disdain and violence. Even when relations were consensual, locals bristled at the Yanks who were “overpaid, oversexed, and over here.”

Soldiers also used their stopovers at transshipment points to straggle, go absent without leave (AWOL), or desert. Given the chance to carouse and get away from the drudgery of orders and chickenshit, many servicemen chose to “extend” their port stay by straggling for a few days. Others went AWOL by leaving their units without permission, only returning days or even weeks later. Some never returned, attempting to go back home, desert for more lucrative work in the defense industry, or even crossing the border to live in Mexico. These three offenses were grouped into a category called “AWOLism,” which saw its highest rates of incidence in the pre-Pearl Harbor period, in 1942, and in 1943.

Troops went AWOL with such disturbing regularity that commanders feared they could not field a force capable of fighting a two-front war. “Absenteeism” became such a burden that in 1942, the War Department published Executive Order 9267, which removed the maximum limits on punishments for going AWOL. Secretary of War Henry Stimson described it as “a deterrent to the alarming increase in the number of such offenses.”2 The Military Police Corps lacked the personnel, funding, training, and support of army leadership to prevent this breakdown of discipline and other abuses. The head of the Corps, General Allen W. Gullion, noted throughout the war that his MPs were operating under half their target strength.3 Soldier-led riots and violent benders marked the all-too-common failures of policing in the army and other branches, and these conflicts provoked domestic and foreign protests against the military.

“When you're A.W.O.L. You're working for the AXIS.” Courtesy of NARA, 44-PA-440, NAID 513899.

Initial attempts by the War Department to clamp down on this practice with harsh penalties backfired when troops seeking to escape the service—and the possibility of a horrible death or injury in combat—realized that going AWOL was a quick path to being discharged. Court-martial trials for these and other offenses also piled up, leaving the army’s manpower locked up in legal affairs or the brig. In November 1942, Chief of Staff Marshall warned his subordinates that the court-martial rate was “far too high” and “unsatisfactory.”4 Each branch eventually came around to simply returning the stragglers back to their ship and reducing or eliminating penalties for offenses like drunk and disorderly conduct. Secretary Stimson encouraged officers to disregard any port sins and warned against “an unwarranted increase in the number of trials by court-martial.”5

“Who Goes AWOL—And Why?” What the Soldier Thinks, no. 2 (January 1944).

Policing & Legal Privileges

By setting a precedent that there would be little punishment for hanging around in port for a few days, or getting into a punch-up at the bar, soldiers were taught that at home and abroad they had extralegal and extraterritorial privileges. This meant that they would not face legal penalties for their actions against civilians. The war effort superseded all other concerns with FDR’s fireside exhortations for collective sacrifice driving civilian deference to the citizen-soldier. In practice, this left civilian cops and even some MPs unable to police the tens of thousands of troops flocking to their cities. Both the army and navy went so far as to try civilians working on military and military-related workplaces in military courts. The army backed up their extraordinary annexation of legal and policing power by relying on the Articles of War, but commanders also took advantage of vague language in legal proclamations, or flagrantly invented legal justifications for their directives.

“Only a Benny Would Say...I Always Relax When I Travel.” Courtesy of NARA, 44-PA-479B, NAID 513950.

The average White serviceman’s relationship with civil police was generally antagonistic (though they typically joined forces to harass or assault Black troops and civilians). Reports from troops, officers, and cops repeatedly capture how soldiers refused to obey the orders of civil authorities. In New York City, for example, servicemen engaged in a 90-minute bar brawl with the local police. Afterwards, the magistrate adjudicating the case told the police they were in the wrong and warned them not to bother troops again. In Long Beach, CA, the police chief warned his officers that “there is a growing resentment against police officers in general by enlisted personnel of the armed forces.” He cautioned that troops were creating “serious difficulties and consequences” for his officers and department. This erosion of civil authority meant that the military controlled more and more space with these urban centers.

The growth of military power led to worsening crime and disorder in American and foreign cities frequented by troops. In a missive to the International Association of Chiefs of Police, General Gullion wrote of rampant “intoxication,” troops “disturbing civilians,” and “general obnoxious disorder” as the ominous signs of a force failing to control its ranks. He warned of “an apparent lack of discipline in the Army as a whole.” Chief of Staff Marshall had earlier shared his fears when he wrote of the “touchy problem in the matter of drinking elsewhere, especially in cities where enlisted men congregate during the week-ends.” Marshall demanded that the MPs find a way to stop what he called the “the mounting wave of criticism and resentment” growing among civilians.

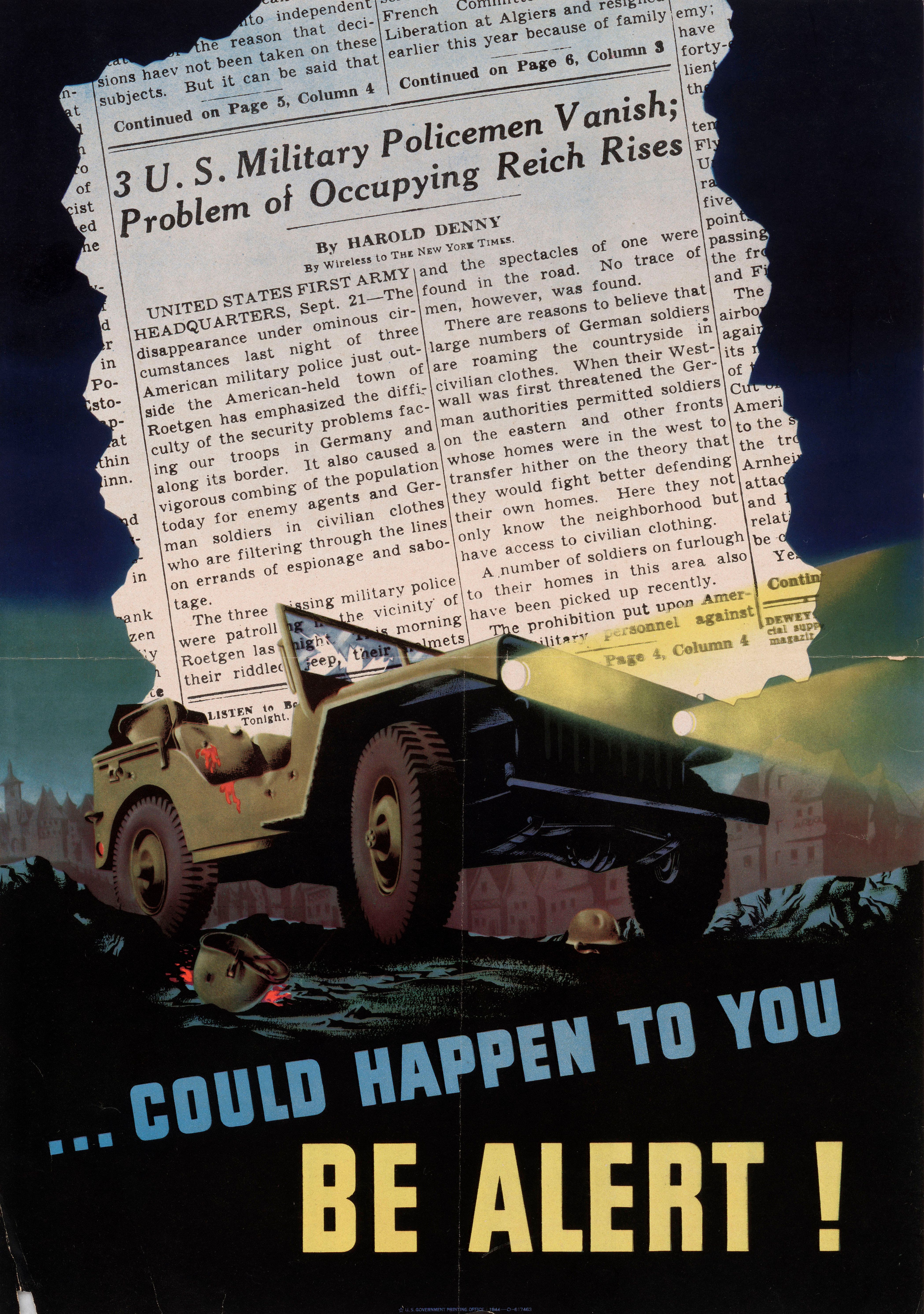

“Could Happen to You Be Alert!” Courtesy of NARA, 44-PA-602, NAID 514082.

But MPs had few resources or means to instill discipline in their fellow servicemen. Throughout the war, MPs worked with severely understaffed units. A 1942 army study also found that the quality of personnel would need to be improved, with many officers getting rid of the draftees they thought of as “unqualified personnel” and “useless individuals” by sticking them in the corps. One investigator found that men in army posts routinely singled out the poor quality of MPs concluding that “the most frightening situation is personnel.”6 Too often, MPs responded to heckling and insubordination from GIs by reaching for the billy club. Reports, however, also show that soldiers would sometimes gang up on lone MPs, reaching for their pistols and attacking them.

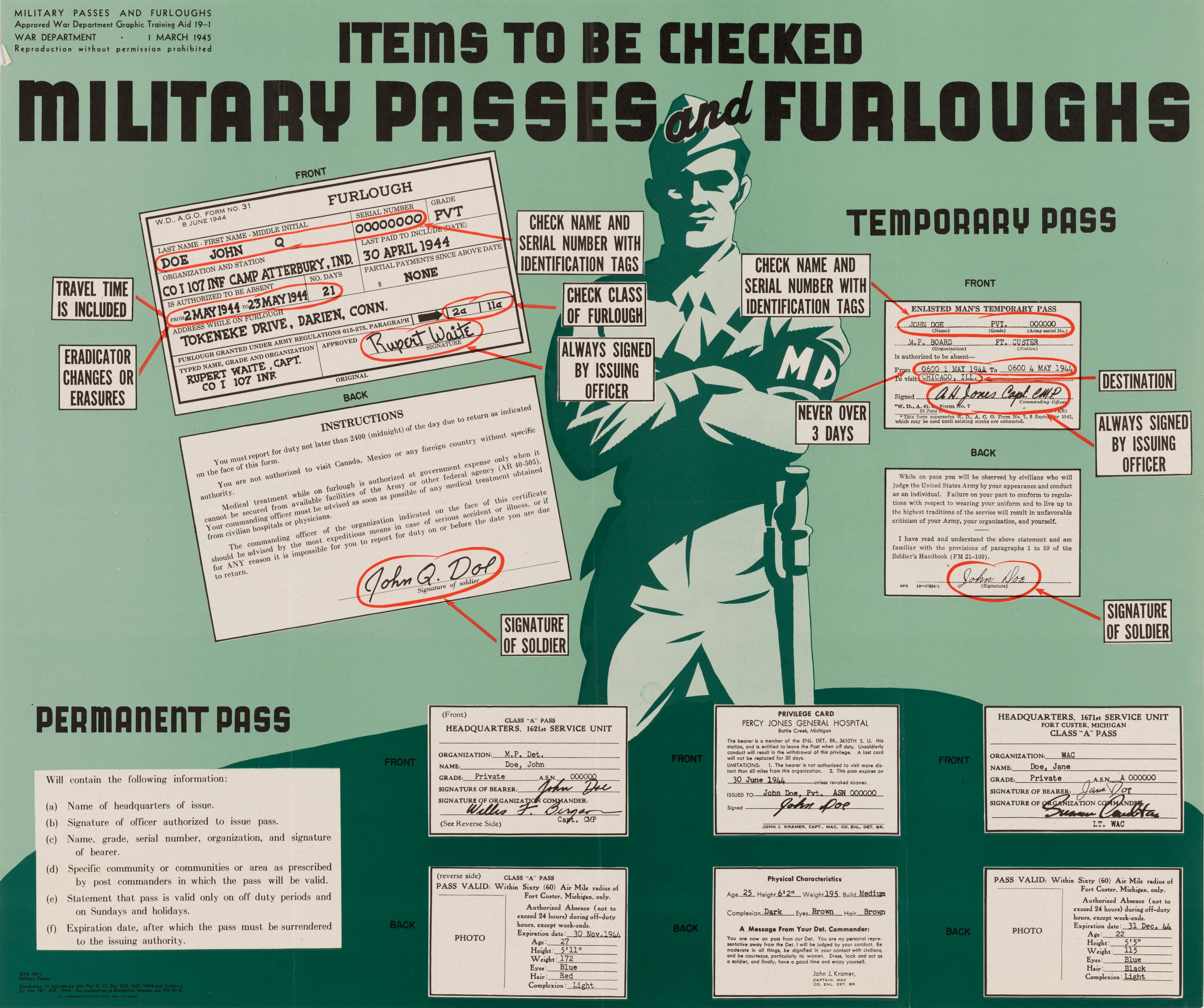

“Items to be Checked Military Passes and Furloughs,” 1 March 1945. Courtesy of NARA, 44-PA-1121, NAID 514648.

While White troops enjoyed incredible legal privileges, Black and other non-White soldiers became regular targets of harassment and violence by police forces. While the excesses of a White GI on leave were excused as “blowing off steam,” or a necessary civilian sacrifice for the war effort, the Black GI was stigmatized as a dangerous menace that had to be aggressively controlled. In Houston, for example, municipal police and MPs coordinated to harass and expel any Black GI from the city. It did not matter that the men had not committed any crimes, one White officer explained. The officer went on to call the men racial slurs and then declare that they would be arrested anytime they came to Houston. In the US and in Europe, Black servicemen regularly faced false rape accusations and other made-up charges, and the army actively pursued a racist strategy of legal harassment and oppression.

The Legacy of Civil-Military Conflict

The US emerged from the war as one of the two key winners, and it had suffered far less than the Soviet Union, which had borne an almost incomprehensible cost to ensure victory. But Americans and foreign civilians experienced a militarization of their lives that could bring not just liberation, but also abuse and crime with little legal recourse. White GIs could treat US and foreign civilians like sanctioned spoils of war with impunity. These wartime battles over indiscipline created postwar tensions, with civilians and governments in places like China and France questioning whether they ought to support a growing US military presence abroad. In the US, the army set about a whole program aimed at making the postwar army a more morally upright, technically adept, and sober force in a bid to improve civil-military relations and to support Universal Military Training. As seen in recurring civil-military conflicts at US bases in strongholds like Okinawa and South Korea, discipline and justice remain contested ideas that shape international diplomacy and the image of the US Armed Forces.

Aaron Hiltner

University College London

Further Reading

Beth Bailey and David Farber, The First Strange Place: Race and Sex in World War II Hawaii (John Hopkins University Press, 1994).

Zach Fredman, “GIs and ‘Jeep girls’: Sex and American Soldiers in Wartime China,” Journal of Modern Chinese History 13, no. 1 (2019): 76–101.

Aaron Hiltner, Taking Leave, Taking Liberties: American Troops on the World War II Home Front (University of Chicago Press, 2020).

Lee Kennett, G.I.: The American Soldier in World War II (University of Oklahoma Press, 1997).

Ruth Lawlor, “Contested Crimes: Race, Gender, and Nation in Histories of GI Sexual Violence, World War II,” Journal of Military History 84, no. 2 (April 2020): 541–69.

Mary Louise Roberts, What Soldiers Do: Sex and the American GI in World War II France (University of Chicago Press, 2014).

Select Surveys & Publications

S-76: Non-Commissioned Officers' Study

S-107: Military Police Study

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 1 (December 1943)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 2 (January 1944)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 6 (May 1944)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 7 (July 1944)

- Lee Kennett, G.I.: The American Soldier in World War II (New York: Scribner, 1987), 68-70.

- “Measures to Forestall Desertions and to Rehabilitate Deserters,” 29 March 1943, 250.4 General, box 65, Administrative Division: Mail and Records Branch, Classified Decimal File 1941-1945, 250 to 251, RG 389 (Provost Marshal General), NACP.

- “Study of Personnel Problems in the Corps of Military Police,” 30 April 1942, box 1185, Military Police Division, Military Police Board Reports, 1942-1947, MP Bd Rpt’s 1-17, RG 389 (Provost Marshal General), NACP.

- “Discipline and Courts-Martial,” 10 November 1942, 250.4 General, box 65, Administrative Division: Mail and Records Branch, Classified Decimal File 1941-1945, RG 389 (Provost Marshal General), NACP.

- “Measures to Forestall Desertions and to Rehabilitate Deserters,” 29 March 1943, 250.4 General, box 65, Administrative Division: Mail and Records Branch, Classified Decimal File 1941-1945, 250 to 251, RG 389 (Provost Marshal General), NACP.

- “Study of Personnel Problems in the Corps of Military Police,” 30 April 1942, box 1185, Military Police Division, Military Police Board Reports, 1942-1947, MP Bd Rpt’s 1-17, RG 389 (Provost Marshal General), NACP.

SUGGESTED CITATION: Hiltner, Aaron. “Discipline & Military Justice.” The American Soldier in World War II. Edited by Edward J.K. Gitre. Virginia Tech, 2021. https://americansoldierww2.org/topics/discipline-and-military-justice. Accessed [date].

COVER IMAGE: “The Corps of Military Police,” Newsmap 3, no. 44 (19 February 1945). Information & Education Division, Army Service Forces, War Department. Courtesy of NARA, 26-NM-3-44b, NAID 66395302.