Allies, Axis & the Aims of War

A total of 8,267,958 Americans served in the United States Army during World War II. They comprised the largest, most diverse military force in the history of the country. They hailed from all regions and backgrounds. All racial groups were represented. About two-thirds were draftees. Though overwhelmingly male, 2.5 percent of the army’s World War II soldiers were actually women who served as Women’s Airforce Service Pilots or who volunteered for the Women’s Army Corps or the Army Nurse Corps. Truly, this was something of a people’s army, one with no parallel in American history, and one that reflected the society it defended more than any American military organization before or since.

Nowhere was the diversity and complexity of these soldiers more apparent than in their varying attitudes and opinions. The men and women in uniform exemplified this richness in perspectives. Before Pearl Harbor, Americans were deeply divided on the question of entry into the war. Interventionists argued for a leading American role in world affairs and support for the Allied cause to the point of entering the war. Anti-interventionists (often dubbed isolationists in historical memory) generally believed that involvement in World War I had been a mistake and had no wish to repeat the experience. The first ever peacetime draft in American history barely passed Congress in 1940 and 1941. The Lend Lease Act of March 1941 enjoyed more support, but many proponents saw it mainly as a way to avoid US involvement in the war by providing Allied nations with the means to do the fighting instead of Americans.

Allies and the the Allied Cause

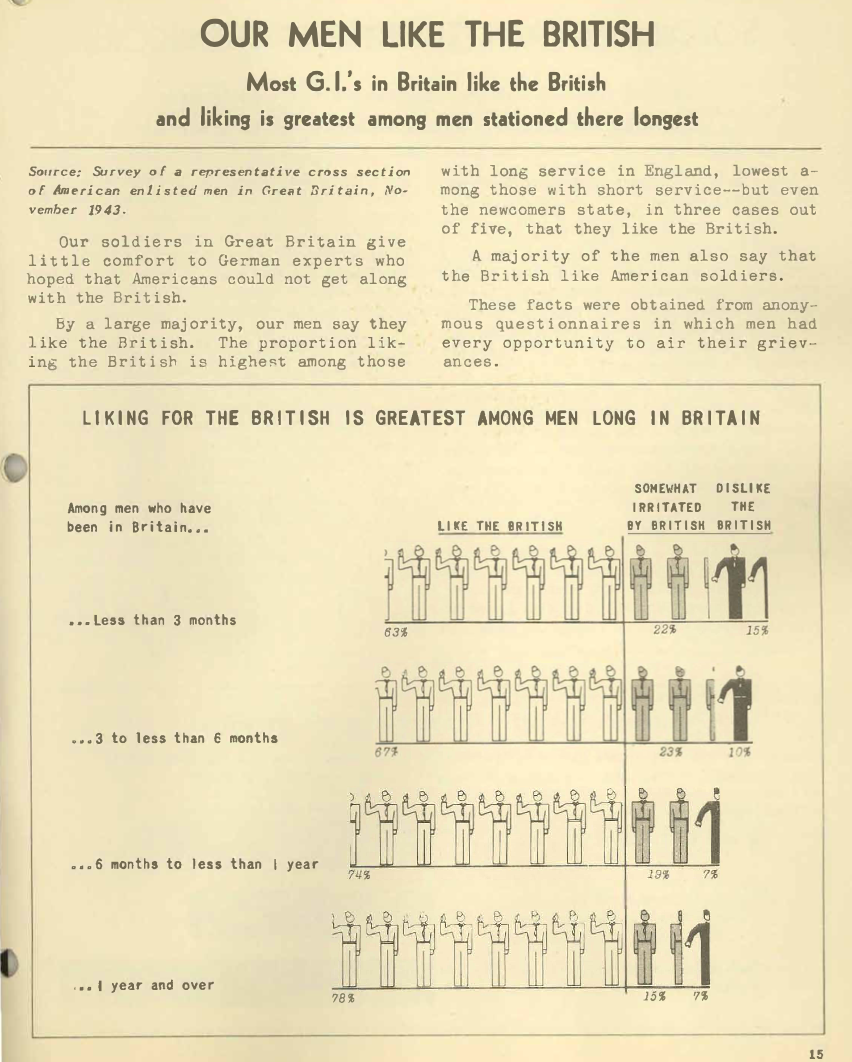

"Our Men Like the British," What the Soldier Thinks, no. 2 (Jan. 1944).

Of course, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and Hitler’s disastrous declaration of war against the US galvanized opinion in favor of entry, but there was by no means a consensus among Americans—many of whom burned with anger against the Japanese—about the wisdom of the Europe-first policy that afforded strategic priority to the war against Germany. In fact, the Research Branch found in 1942 that “two in five [soldiers] distrust our English allies and the average enlisted man has a relatively low opinion of them as fighters.”1 Despite this, most soldiers did come to respect their British comrades and the British people as a whole. When US troops stationed in the British Isles were asked two months before the invasion of Normandy how they thought the average British soldier “stacks up as a fighting man,” the vast majority (93 percent) responded “fairly good” or “very good” (Survey 122).

As far as the Allied cause itself, the average soldier did believe that the US had entered the war to defend and guarantee democratic liberties for all people around the world. But this same survey—the first conducted in the European Theater after troops started amassing on British shores—also revealed that between a quarter and a half of the men doubted the reasons the US had entered the war or were cynical about its aims. A full half of the surveyed airmen agreed with the statement, “This war is the old story over again. Europe gets itself into a mess and then yells for Uncle Sam to help set things straight again.” The same percentage of men who doubted the aims of war, not surprisingly, showed a similar lack of strong personal motivation to fight and preferred to avoid combat service. The army responded to the secret report of these unfavorable findings by creating Why We Fight, a series of required-viewing orientation films aimed at shoring up support and troop motivation.

Hatred of the Enemy

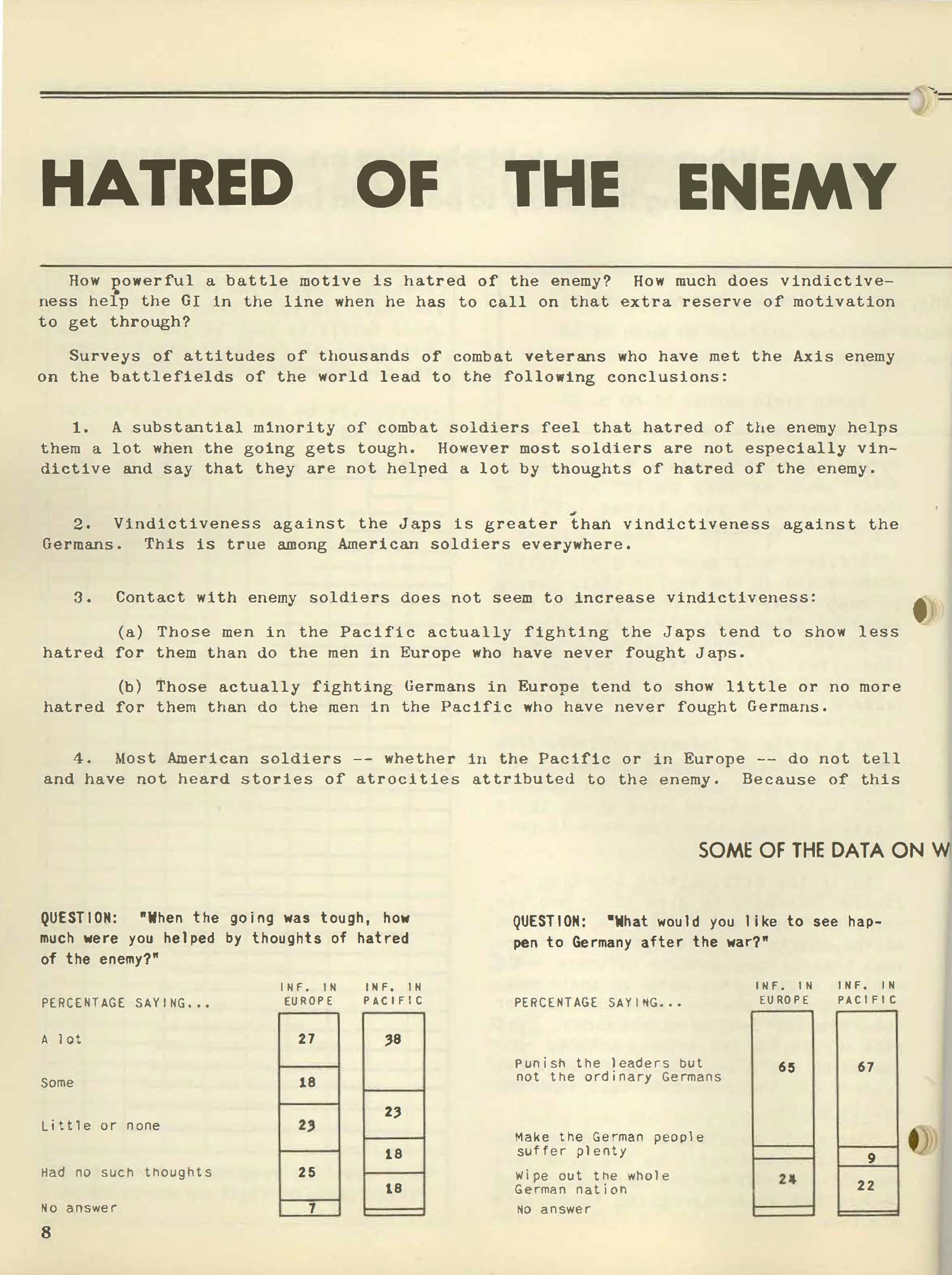

“Hatred of the Enemy,” What the Soldier Thinks, no. 7 (July 1944).

Ideals hardly sustained the soldier in combat. In heavy action, combat infantrymen were motivated to fight primarily by kinship with the men around them, much more so than by the mere abstraction of the Allied cause. Hatred of the enemy also played a role in combat motivation. Almost half of American infantrymen attested to the fact that their loathing for the Germans or the Japanese motivated them to fight. The degree to which the average soldier felt vindictive toward their enemies varied considerably. When soldiers were asked what they thought should happen to each country after the war was over, about a quarter of the men who were surveyed selected the option “Wipe out the whole German nation.” Only a small fraction thought the German people should have to “suffer plenty.” Contrast that to how soldiers felt about Japan: A full 58 percent of US infantrymen stationed in Europe wanted the whole nation wiped out, and 10 percent wanted the Japanese people themselves to suffer. Infantrymen in the Pacific were more likely to want to see Japan’s leadership punished, but 42 percent still wanted the whole nation wiped out.

These views would continue to diverge. Hatred toward German citizens and soldiers diminished, especially after April 1945. In fact, the same portion of soldiers who had a favorable opinion of German citizens had a similarly favorable opinion of the French. Contact between US soldiers and German youths and elderly citizens softened opinions considerably that summer. The average soldier still wanted the Nazi leadership punished. They wanted the Allies to have a strong occupation force in the country for an indefinite period, and they wanted certain German industries prevented from rebuilding. But they also thought a majority of Germans were capable of being “educated for a democratic society and of becoming a trustworthy nation” (Survey 235).

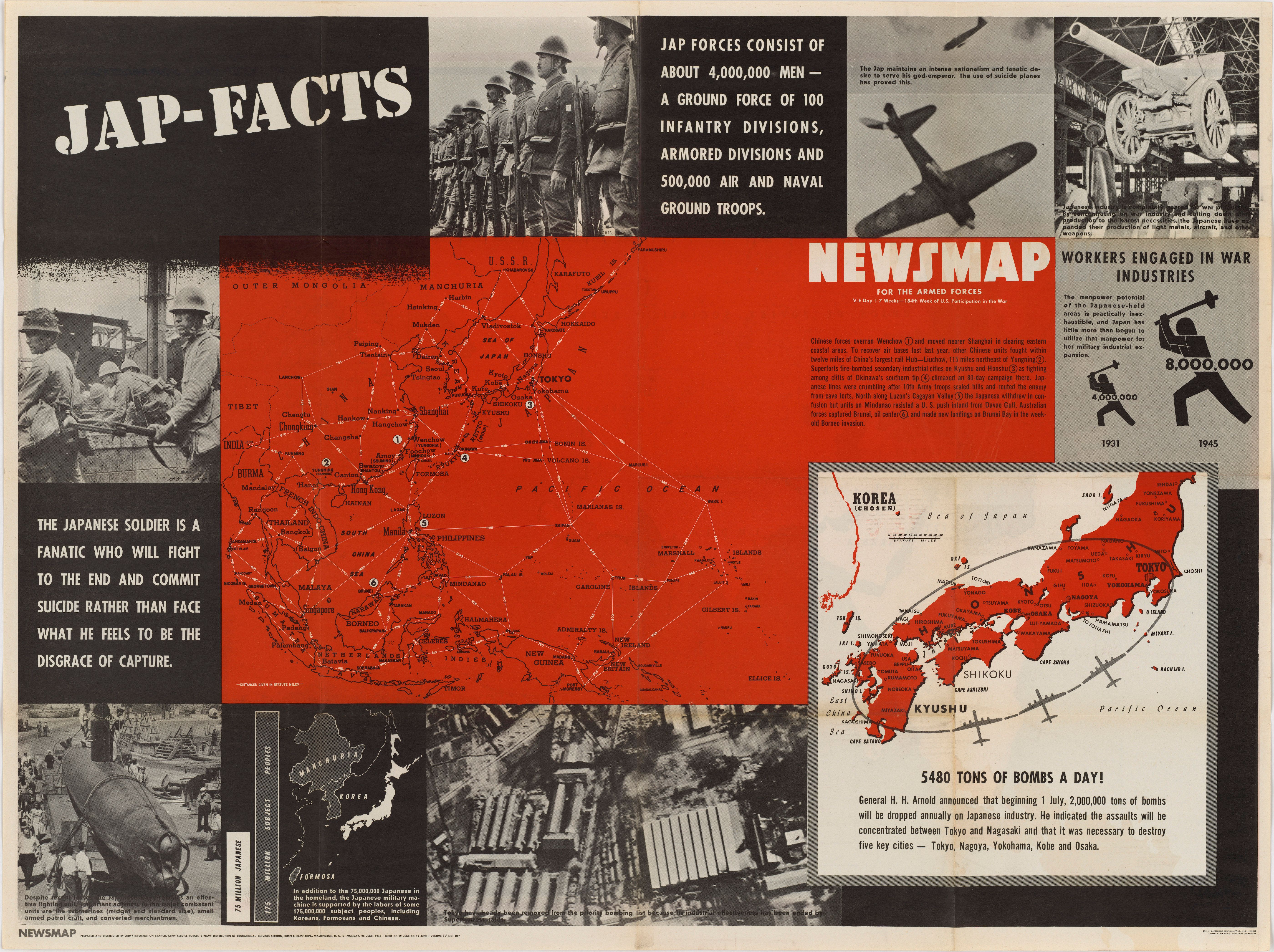

But when enlisted men in stateside redistribution centers were asked that summer what the US should do if the Japanese offered to stop fighting and work out peace terms, the majority continued to believe that the Allies should give their enemy no leave. Sixty-four percent thought the US should keep fighting until Japan was completely beaten (Survey 218B, Q.26). Issue Eleven of What the Soldier Thinks reported that the very same percentage of surveyed enlisted men representing air service troops in the Pacific believed the Japanese were very or fairly likely to use gas against US troops. The policy of “unconditional surrender” was not only an element of grand strategy, a decision that was made by Allied leaders behind closed doors; it had also been soldier approved.

“Jap-Facts,” Newsmap, 4, no. 10, 25 June 1945. US Army Information & Education Division. Courtesy of NARA, 26-NM-4-10; 26-NM-4-10b, NAID 66395332.

Longing for Home

US troops fought on distant battlefields, sometimes in exotic, obscure places like Bougainville, New Georgia, Buna, Los Negros, Biak, and Cebu, whose names have hardly endured in American popular memory as have others, such as Normandy, Iwo Jima, and the Ardennes. Perhaps inevitably, combat soldiers resented those who had safer jobs in rear areas. Even more, they nursed grudges against soldiers who never deployed overseas. “It’s hard as hell to be here and read in every paper that comes from home [that] Pvt. Joe Dokes is home again on furlough after tough duty as a guard in Radio City,” one sergeant commented sardonically. Another private complained of those who never left the States: “Every paper we get from home usually shows several of the Canteen Commandos on furlough. With two major battles behind us we should get the same break” (What the Soldier Thinks, no. 8 (Aug. 1944), p.3).

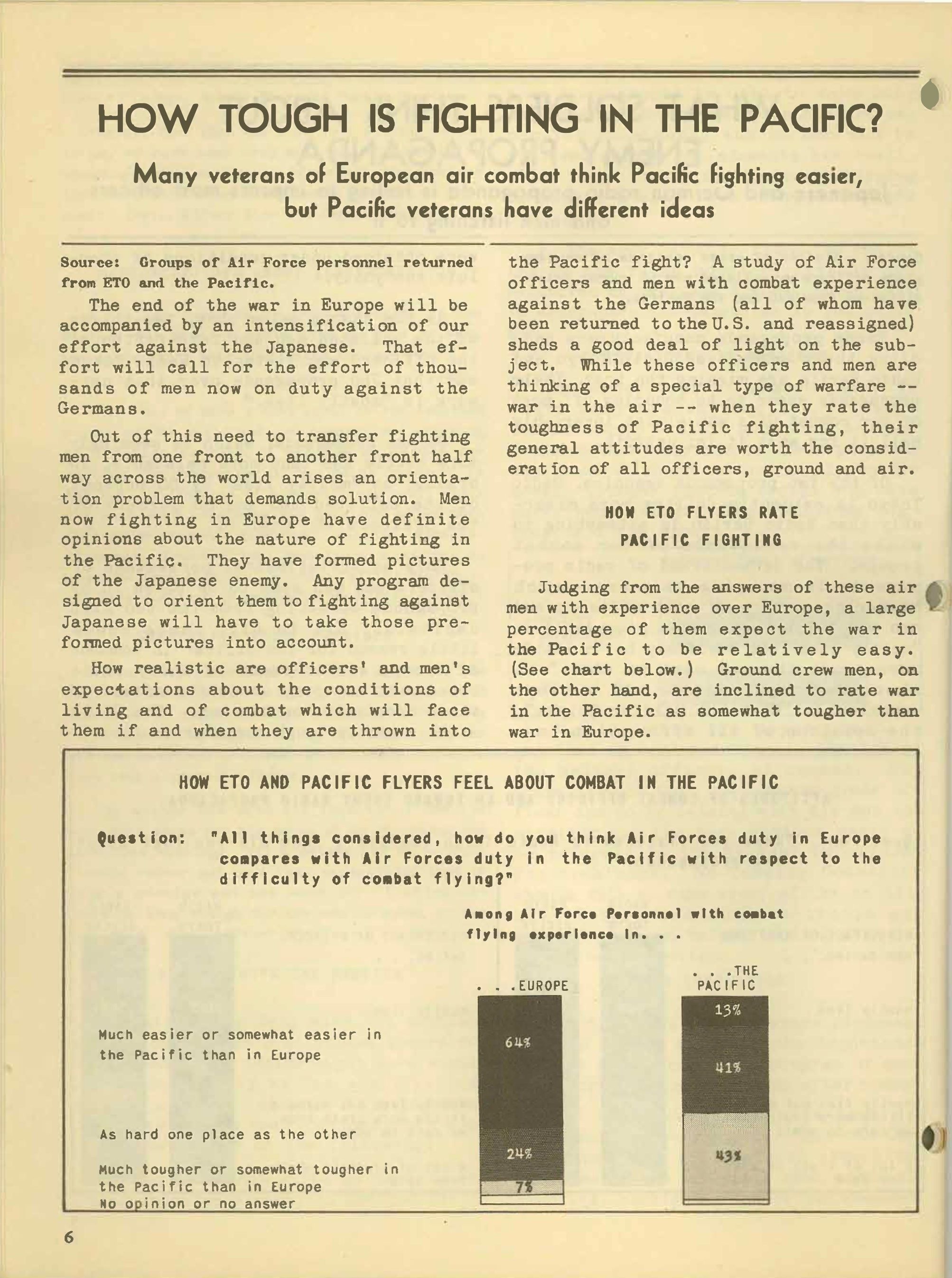

“How Tough Is Fighting in the Pacific?” What the Soldier Thinks, no. 8 (Aug. 1944).

The average soldier who deployed overseas spent sixteen months away from the United States. Whether or not the average GI hated the German or the Japanese soldier, the longing for home and peace was felt universally. “I would like to see every man returned to civilian life as soon as possible after Japan is crushed,” wrote one enlisted man weeks before the US attacked Nagasaki and Hiroshima, bringing the war to an end. Most soldiers never wavered from the belief that folks back home did all they could to help win the war. But they also felt that civilians could never truly understand the realities of the war for those who fought it. “Hell, they don’t even know there’s a war on,” many complained of Americans on the home front, including even their own family members (The American Soldier, Volume II: Combat and Its Aftermath, p. 320).

We know this kind of fascinating information because of a remarkable effort on the part of social scientists to administer surveys to American soldiers all over the world, on every fighting front, in order to learn about their true opinions and attitudes in relation to everything from combat motivation and morale to psychoneuroses and postwar readjustment back home. The very existence of this herculean effort—one that was unprecedented in world history up to that time—spoke volumes about the importance Americans placed upon notions of public opinion and the intrinsic value of the individual. If public opinion mattered in a political sense, then it must also matter in the armed forces, composed as they were of citizen soldiers, most of whom were themselves empowered to vote. Beyond the obvious historical value of knowing the innermost thoughts of the average GI, we might also observe that this kind of personal empowerment embodied much of what the soldiers fought for in World War II.

John McManus

Missouri S&T

Further Reading

Stephen E. Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers: The U. S. Army from the Normandy Beaches to the Bulge to the Surrender of Germany (Simon and Schuster, 1998).

Rick Atkinson, The Liberation Trilogy (Henry Holt and Co., 2013).

Eric M. Bergerud, Touched with Fire: The Land War in the South Pacific (Penguin Books, 1997).

Lee Kennett, GI: The American Soldier in World War II (University of Oklahoma Press, 1997).

Gerald F. Linderman, The World Within War: America's Combat Experience in World War II (Harvard University Press, 1999).

John C. McManus, The Deadly Brotherhood: The American Combat Soldier in World War II (Presidio Press, 2003).

John C. McManus, Fire and Fortitude: The U.S. Army in the Pacific War, 1941-1943 (Dutton Caliber, 2019).

Peter Schrijvers, The Crash of Ruin: American Combat Soldiers in Europe during World War II (NYU Press, 2001).

Peter Schrijvers, Bloody Pacific: American Soldiers at War with Japan (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

Select Surveys & Publications

S-122: Soldier Attitude Survey, Anglo-American Relations

S-211: Returnees Reaction to the Enemy and Further Duty

S-218: Redeployment and Demobilization

S-235: Westbrook Follow Up

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 8 (August 1944)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 15 (July 1945)

- “Attitudes of Troops Toward the War: Based on Planning Surveys of Representative Cross Sections of Troops in the Army Ground Forces and Air Forces,” Report No. 28, 8 Sept. 1942.

SUGGESTED CITATION: McManus, John. “Allies, Axis & the Aims of War.” The American Soldier in World War II. Edited by Edward J.K. Gitre. Virginia Tech, 2021. https://americansoldierww2.org/topics/allies-axis-and-the-aims-of-war. Accessed [date].

COVER IMAGE: "A Gruppe is the basic unit of German Infantry," Newsmap, 1, no. 8 (15 June 1942). Army Orientation Course, Special Service Division, Army Service Forces, War Department. Courtesy of NARA, 26-NM-1-8b, NAID 66395003.