The Citizen-Soldier

Before World War II, the US government had never instituted military conscription while not at war. Americans have objected to standing armies going back to the garrisoning of British troops in colonial Boston. In the War of 1812, the Massachusetts Federalist representative Daniel Webster bemoaned the entertaining of compulsory military service in the “councils of a free government.”

“The question is nothing less than whether the most essential rights of personal liberty shall be surrendered, and despotism embraced in its worst form,” he asserted. Military service must not be coerced but freely chosen in a republic. Only a volunteer army could remain true to the nation’s founding principles and character.1 Historian Alan Taylor argues that this distinction was at the heart of the conflict with Britain, its casus belli.

Debates about military service force a people and a nation to confront the bonds and boundaries of citizenship and civic life, responsive to the political pressures of the day. Could the Confederate States of America arm enslaved people in its civil war with the North but deny them citizenship and call itself a republic? World War I capped a streak of mass international migration. Should a new immigrant be compelled and trusted to serve when their native country was a belligerent nation?

The years between the world wars are known for the economic upheaval of the Great Depression. It was also a period of cultural ferment and social transformation. Education levels rose, women could vote, white-collar employment expanded, immigration was restricted, and Black Americans continued their exodus from the South. These transformations set new expectations as the country took up and enacted a peacetime military draft that, in effect, blurred distinctions between citizen and soldier. That blurring helped win the war. Yet it endured long after the Allies had defeated Japan and Germany.

World War II has been portrayed as a war to save democracy from the clutch of despotism. Yet the drive to institute a draft in the summer of 1940 was hardly a model case study in democratic governance. The Roosevelt administration and Congress would allocate two billion dollars to up-front war mobilization but balked at taking citizens from home and hearth and their jobs. Elections were fast approaching, after all.

Alarmed by the decimation of European states, a coterie of the nation’s ruling elite—former cabinet members and military officials, international bankers, Wall Street lawyers, and corporate executives, among others—rushed into the breach. They drafted a conscription bill that neither FDR nor Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall supported and that also sparked fierce public resistance.

Skirting “Hitlerism”

National leaders backing the measure had to overcome protestations not only over the bill’s secretive elite origins but an even more incendiary charge—that by passing the draft the US would be adopting the tactics of Hitler and Mussolini. Policies had been enacted and an agency created in World War I to more closely align conscription with the recognizable features of US democracy and to ensure that the obligation of national service was shared more equitably than it had been.

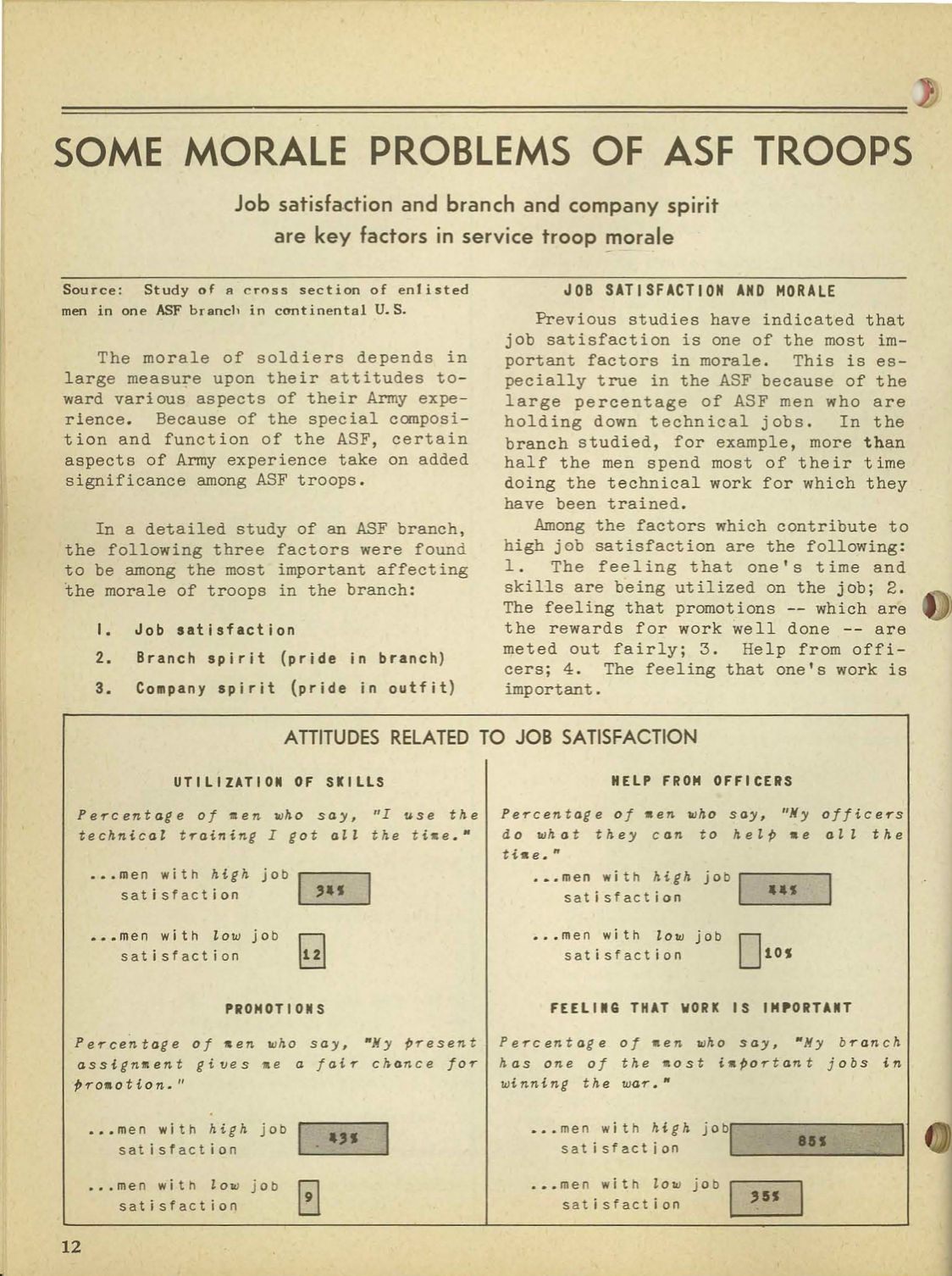

Staff photographer, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Draft registration at Jefferson Street car barn, 16 October 1940. Courtesy: University of Washington Libraries & Museum of History & Industry, Seattle (MOHAI), Image no. PI28229.

The War Department had turned the draft over to a new, independent, and primarily volunteer-staffed civilian agency—the US Selective Service System, for instance. Registration and evaluation of potential selectees was also decentralized, falling upon local draft boards. These were staffed with community leaders and drawn using voting precinct maps—as though the two, voting and registering, were civic activities of equivalence.

Nevertheless, for many Americans the parallels between compulsory military service and authoritarian military regimentation were simply too inimical. “Peacetime conscription is totalitarianism! Keep Democracy! Halt Regimentation! Stop conscription!” read one opposition ad.2 Proponents of the bill doubled down. They insisted that conscription was not only better than voluntarism on practical grounds, that it would secure more men and do so more rapidly and efficiently, but they asserted it was also more democratic.

Military training and service should fall not on the willing alone but be shared equally, by all, or at least all draft-eligible men, they argued. Passed and signed into law on September 16, after many weeks of intense and even violent debate, the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 retained its essential World War I civic structure and made more allowances for non-combat service.

But the campaign that had been waged to convince Americans that compulsory peacetime service was democratic and to push the measure through a divided Congress, over the protests of so many, left a distinct mark on mobilization and the expectations of the public. Men subject to the draft were promised that their year of service would not be wasted but that they would receive valuable training—yes, training for war but training that would serve them well whether the US entered it or not.

A Citizen-Soldier Army

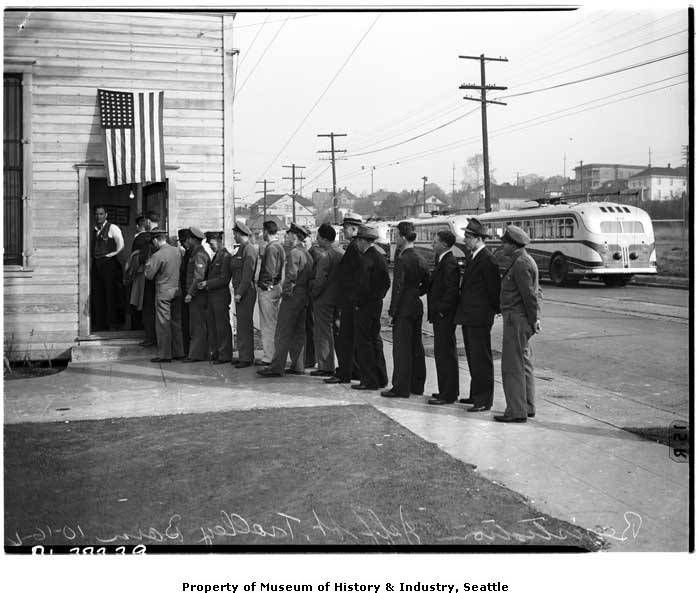

"Just as a Lady Justice is traditionally portrayed with a blindfold to emphasize her impartiality, so, too, is the god of war in Clifford Berryman’s October 29, 1940, cartoon “Waiting for His Number!” commemorating the US’s first peacetime draft lottery. American cartoonists, journalists, public officials, and other thought leaders depicted compulsory military training as a matter of pure luck to drive home the point that national service was a shared, equitable obligation and that one’s race, religion, wealth, or status should play no role whatsoever." Courtesy of NARA, Z-030, NAID 6012221.

The campaign to convince Americans continued even after the bill became law. Days after, Marshall issued a directive, which was also released to the public, that stressed the importance of a smooth assimilation of selectee civilians into the military and the responsibility of all in command to maintain high troop morale toward that end. "Our Army will be an Army of citizen-soldiers and must be essentially a democratic institution,” he instructed them while also assuring mothers and fathers and the fourteen million young men who would find themselves filling out a draft card at their neighborhood voting precinct.3

This moniker of citizen-soldier, which quickly suffused American culture, was a shorthand reminder: in a democracy the benefits of citizenship and obligation of military service were bound together. In lockstep, the one followed the other. Yet, the military was not a democratic institution. Women were excluded from the draft, and while African Americans were represented proportionally, Americans were assured that the armed forces had no intention of intermingling troops. It was also by tradition hierarchical. Still, who could fault citizen-soldiers for believing the rhetoric that the army the US was amassing would be not only a force for democracy, but democratic itself?

“We are a democratic race, bread [sic], born, and raised by the freedom of a democracy,” wrote a White enlistee in the Ninth Division right after Pearl Harbor. “How can anyone expect to erase all this by one year of severe training?” The potency of ideological rhetoric, which infuses this soldier’s comments, as it did US culture writ large, helps account for the clash of citizen expectations with the reality of martial discipline and the army’s rigid, anti-democratic hierarchy.

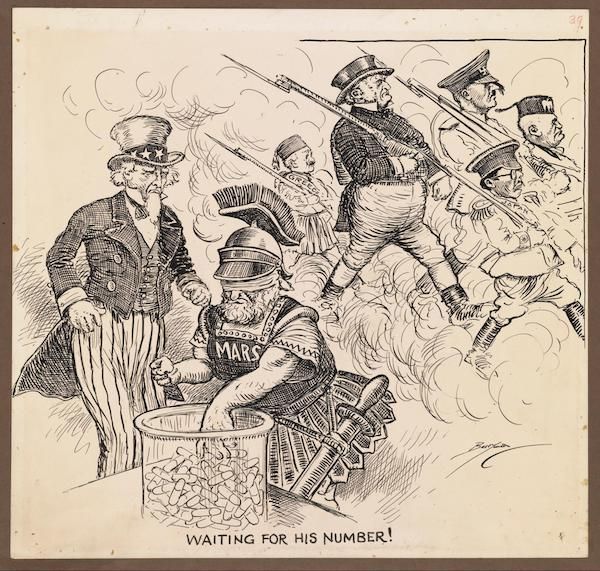

Many GIs shared this soldier’s frustration, which the army researchers studying morale attributed, in the main, to what was an otherwise positive development: an extraordinary expansion of education. Whereas in 1916, right before the US entered World War I, 1.7 million youths had been enrolled in high school and 400,000 in college, by 1940 those figures had rocketed to 7.1 million in high school and 1.4 million in college.

These gains were reflected in the country’s citizen army. Nearly 80 percent of World War I draftees had no more than a grade school education and only 4 percent had finished high school. But draftees in 1940 with only a grade school education had dropped to 31 percent. And now nearly the same had completed high school. Many of the new enlistees looked down on and derided their commanding officers as backwards, the “Old Regulars,” who had volunteered before to the draft. But the Old Regulars were also more educated than their World War I counterparts (Chart I).

Samuel Stouffer, et al., The American Soldier: Adjustment during Army Life, Vol. I (1949).

The more-educated the enlistee was, army researchers concluded, the more likely they were to have enjoyed certain social and economic privileges as civilians, and with those privileges certain expectations. This started with how they should be treated in this democratic army, especially by their commanding officers: with dignity. The new breed of White, educated enlistees bucked “army ways” and the military’s hierarchical, or “caste,” system.

In its initial assessment, army researchers noted, with surprise, the most “radical change” among Black enlistees, however. About four out of five Black World War I draftees were Southern. A considerable number of these Southern enlistees were illiterate; only 3 percent had ever attended high school. Many Northern Black draftees were recent transplants and also illiterate, with only 14 percent having ever attended high school.

Compare these statistics to World War II, as army researchers did. Nearly one in three Black enlistees were now drawn from the North, 63 percent had attended high school, and almost a quarter were high school graduates or college men.4 Education levels still lagged in the South, although eleven times the proportion of Southern Blacks had attended high school than had in the teens.

That so many educated Northern Black draftees found themselves compelled to return to the South, where many army posts were located, was problem enough. That they were also compelled to serve under Southern White officers who may have had less education added insult to multiple injuries.

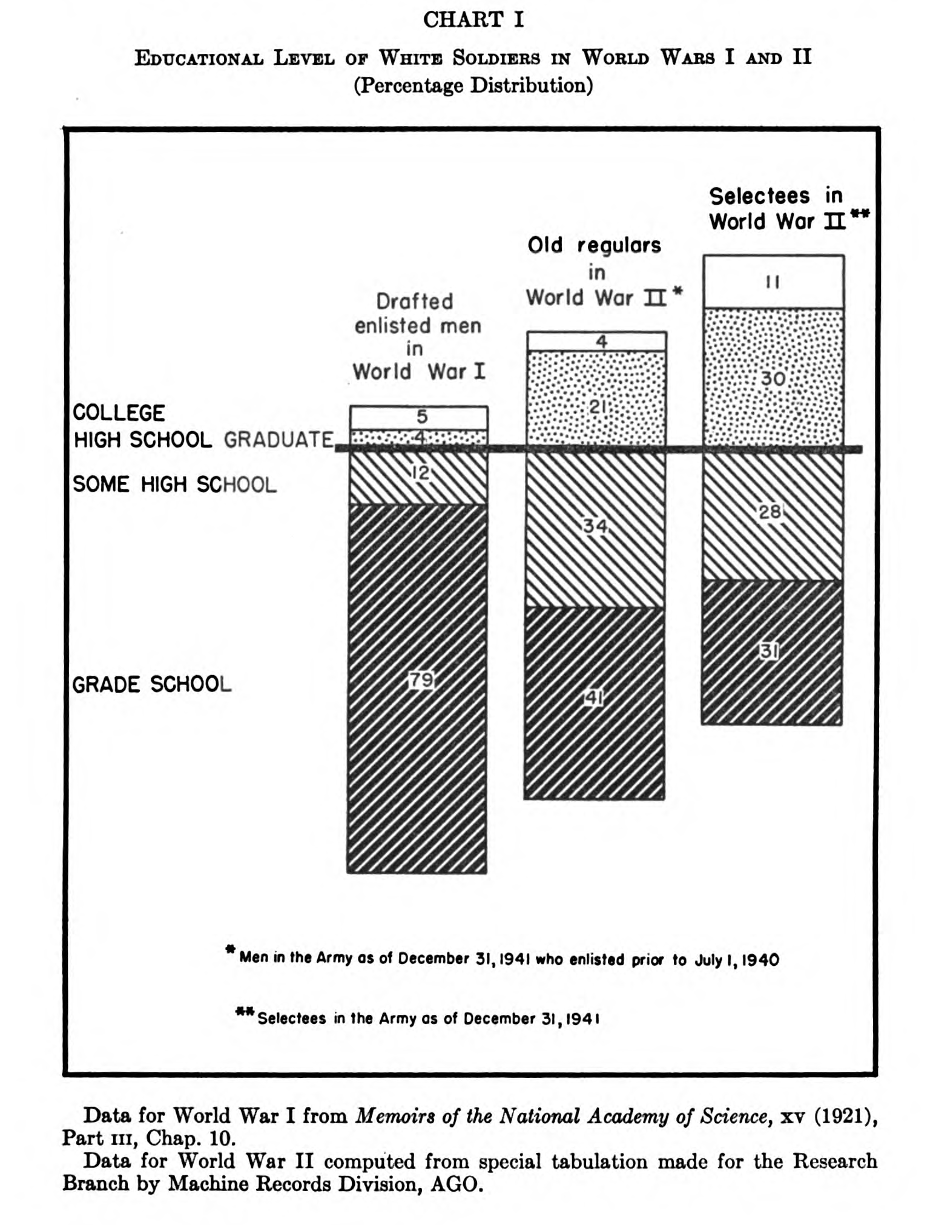

Job Satisfaction

“Why do I as a Negro wear the uniform and fight the Germans because of things that they have done and the same things are being done my own people here in this Country. The Germans deny a minority group the privileges of working at profitable jobs and permit them only the most menial. In Democratic America the same thing exists,” wrote one Black servicemember, believing the US as guilty as Germany for perpetuating the “evil practice” of segregation. He wanted this evil done away with. He also wanted an opportunity to work at a profitable job.

Black soldiers like this GI believed that the benefits of national service, and of the training and opportunities the government promised, should extend to soldiers of color no less than to their White comrades. Both had entered the military expecting that in a democratic army the education and civilian training, skills, and work experience they possessed would be put to good use.

By the lights of many inductees, especially those with professional civilian work experience, democratic ideals and principles were to assume a particular organizational pattern or form. Namely, they wanted their new employer to function as any other modern organization or corporation. “Personally, I think the army is very inefficiently organized—That the training I have received could have been given in three mos. at the most. The army itself is the biggest breaker of moral[e],” one infantryman complained.

“The army is not and does not take advantage of its man resource,” he explained. “Men do not liked [sic] to be treated as if they were just toys and dogs for someone else to play with. We are entitled to the respect we have worked for and earned in civilian life.” While researchers studying troop morale detected an inverted correlation between poor adjustment and advanced education, they observed another near-parallel correlation. College-educated enlistees who were poorly adjusted (the majority, 60 percent), as this soldier was, believed the army was not making use of their civilian skills and abilities.5

The “greatest concern of the soldiers,” researchers concluded, “was to do something which gave scope to their conception of their own ability.” The month after this first survey was conducted, the army ordered the review of every enlistees’ civilian qualifications and army placement in one week’s time for possible reclassification and reassignment. The proper “utilization of manpower,” as command put it, was not only in the soldier’s best interest; it was also in the interest of an organization needing to modernize itself at an extraordinary pace to meet the demands of a logistically complex global war.

Indeed, in addition to infantrymen, tank drivers, and manual laborers, the army needed electricians, surveyors, supply clerks, technicians, engineers, opticians, radiotelephone operators, statisticians, and myriad other professionals. At peak strength, the army had eight million members, among whom more than three-quarters of a million were officers. Roughly one out of every four of these citizen-soldiers was in a skilled job, the second was in a semiskilled or unskilled role, and the third was in a clerical position.6 Only one in four occupied a combat role.

The Effective Utilization of a Nation’s “Manpower”

Many a citizen-soldier never felt the military had effectively utilized their civilian education, training, skills, and experience. This was certainly the case for a great many African Americans (even if more were eventually allowed to become officers), and also for women, who had been entirely excluded by the System and could only volunteer for limited roles. The hierarchy was never truly flattened.

Still, the emphasis on the harrowing experience of combat in popular treatments of the war obscures a redefining of citizenship through military service brought about by the interwar-period expansion of education and white-collar employment, compulsory service as a peacetime measure, and the multifaceted needs of the most expansive, complex, resource-intensive organization in all of US history.

Not only did the Army query troops about the draft as a wartime measure, but well advance of the war’s end, the Research Branch did extensive surveying of enlisted personnel and officers about Universal Military Training (UMT) and their own desire to continue to serve. President Roosevelt’s January 6, 1945, State of Union address, which once again urged Congress to pass a National Service Law—as well as draft nurses into the Army—accelerated the need for reliable data as Congress prepared to hold hearings that spring.

The Forever Citizen-Soldier

No longer was the citizen-soldier a provisional status, permissible for the needs of fighting an incumbent war. Toward the war’s end, advocates of national service launched a new coordinated campaign to codify the citizen-soldier relationship in perpetuity through universal military training. Their drive failed. The draft was also allowed to expire in 1946 as planned. Only it was revived two years later, at which time the warfare state could continue its “channeling” of the nation’s manpower. And so it did, for another quarter century.

Ed Gitre

Virginia Tech

Further Reading

Benjamin L. Alpers, This is the Army: Imagining a Democratic Military in World War II,” Journal of American History 85, no. 1 (June 1998), 129–63.

J. Garry Clifford and Samuel R. Spencer, Jr., The First Peacetime Draft (University Press of Kansas, 1986).

Paul Fussell, Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War (Oxford University Press, 1989).

James Jones, World War II: A Chronicle of Soldiering (1975; University of Chicago Press, 2014).

Christopher P. Loss, “‘The Most Wonderful Thing Happened to Me in the Army’: Psychology, Citizenship, and American Higher Education in World War II,” Journal of American History 92, no. 3 (December 2005), 864–91.

James T. Sparrow, Warfare State: World War II Americans and the Age of Big Government (Oxford University Press, 2013).

- Daniel Webster, Daniel Webster on the Draft: Text of a Speech Delivered in Congress, December 9, 1814 (Washington, D.C.: American Union Against Militarism, 1917).

- “Stop the March to War! Peacetime Conscription is NOT the American Way!” New York Times, July 12, 1940, 10.

- “Chief of Staff Issues Instructions to Commanders on Morale,” 30 September 1940, fol. Special Services Division 1944, box 42, Gen. Sub. Files, 1942-1946, Joint Army and Navy Committee on Welfare and Recreation, RG 225, NARA.

- “Some New Statistics on the Negro Enlisted Man,” Report No. 2, 17 February 1942, Research Division, Special Services Branch, fol. Report No. 2, 2-17-42, box 989, entry 93, RG 330, NARA.

- “Planning Survey,” Report No. 1, 5 February 1942, box 989, RG 330, NARA; “Job Assignment and Job Satisfaction Among Enlisted Men,” Report No. 3, 9 March 1942, box 989, RG 330, NARA.

- Stouffer, et al., The American Soldier, vol. I (1949), 232, 312.

SUGGESTED CITATION: Gitre, Ed. “The Citizen-Soldier.” The American Soldier in World War II. Edited by Edward J.K. Gitre. Virginia Tech, 2021. https://americansoldierww2.org/topics/the-citizen-soldier. Accessed [insert date].

COVER IMAGE: "Progress Report on Demobilization," Newsmap 4, no. 32 (26 November 1945). Courtesy of NARA 26-NM-4-32b, NAID 66395389.