Recreation & Welfare

The US Army had a very clear motivation for its frequent surveys of soldiers’ preferences for equipment, rations, and off-duty activities. In attempting to build and maintain the most efficient and effective force possible, the army developed detailed training programs, established a massive medical enterprise to keep soldiers healthy and heal wounds, and worked closely with industry to develop and distribute the weapons and equipment to supply a global undertaking. At the same time, the army worked assiduously to raise morale among its soldiers, to ensure that the massive force it was raising, training, and equipping would perform at the highest levels in combat, and sought constant feedback on the effectiveness of its efforts. The welfare and recreation programs established in the World War II US Army, and continued in the post-war period, had one immediate goal: to keep soldiers as fit for combat as possible—primarily physically, but also mentally, morally, and spiritually—by lifting their morale and making them enthusiastic about their significant responsibilities.

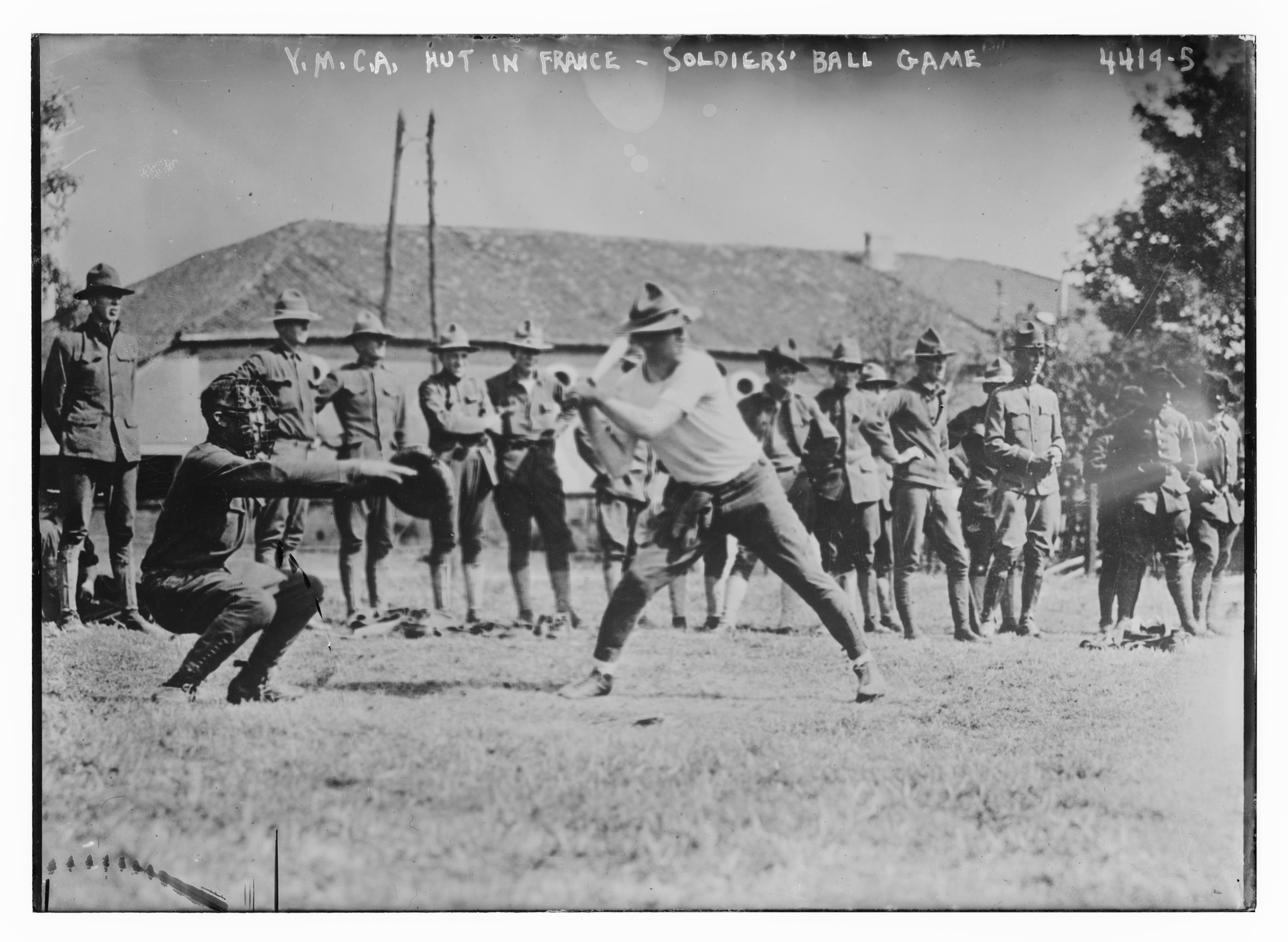

“Y.M.C.A. hut in France—soldiers’ ball game,” [c.1917]. Courtesy of Lib. of Congress, digital ID ggbain 25770.

For millennia, armies have worked to preserve combat power by keeping soldiers as healthy as possible, whether by ensuring adequate caloric intake or performing basic camp sanitation. But the concept of the citizen-soldier unleashed in the French Revolution opened the eyes of military commanders to the powerful benefits of soldier morale—willing, motivated soldiers defending their homeland could fight more willingly, require less discipline, and endure more hardships, as the fledgling Continental Army had demonstrated decades earlier. Thus, the army sought to bolster a soldier’s spirits as well as his health, by keeping him as contented as possible and focused on achieving victory so that he could return home safely to his loved ones.

The army’s efforts to provide “wholesome” activities to fill the hours not occupied by training or combat included recreational activities, such as organized sports (baseball, basketball, and volleyball were among the favorites) as well as individual outdoor recreation, including swimming, fishing, and horseback riding. To support these efforts, private organizations with vested interests pitched in; major league baseball teams donated over 80,000 pieces of equipment, including balls, bats, and gloves.1 Sightseeing tours, “shows” (whether live or recorded on film), and spectator sports, especially the widely popular boxing matches, also presented entertainment options that kept soldiers away from the vice dens.

“Two American Red Cross girls joined twenty war-weary youths of the 15th Army Air Force on tour of the famous grottoes along the Italian seacoast. Here, left to right: Miss Tilly Jane Reed of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania escorted by Sgt. Percy Johnson, airplane engine mechanic from Monroe, Louisiana and Miss Betty Baker of Maplewood, New Jersey escorted by S/Sgt. Bob Stenard, waist gunner, from Brooklyn, N.Y., board an Italian bus which the airmen’s outfit had picked up as a prize of War.” Courtesy of NARA, 342-FH-3A24360-68119AC, NAID 204912193.

Most training posts organized dances, with local community groups offering to chaperone and providing dancing partners—an easier task as the nation mobilized and removed more and more eligible young men from towns and cities across the country. These dances, sponsored by church groups, the Red Cross, and the newly formed United Services Organization (USO), provided soldiers the potential for companionship away from the bars and nightclubs they might otherwise frequent. Some posts even conducted self-improvement classes, whether basic literacy for those soldiers with deficient educational backgrounds, or classes aimed at acquiring additional skills, such as painting, photography, or learning a foreign language.

Army Services & Organized Religion

The army’s interest in determining which of these activities soldiers preferred aligned with those of many faith-based organizations, who wanted to ensure that soldiers were able to practice the tenets of their faith while avoiding temptations that might cause them to stray from the flock. Even the modern army emphasizes a “spiritual fitness,” recognizing that soldiers with stable and intact belief systems are better able to withstand the strains of combat, moral crisis, and physical separation.

The army continued to provide direct religious support through chaplains, who ranked as commissioned officers and remained under army control. While chaplains had to be ordained through their respective faiths, service in the army created a spirit of ecumenicalism that focused more on a soldier’s individual welfare than harvesting more souls. In addition to regular Sabbath services, chaplains also organized bible study during the week (many training schedules left Wednesday afternoon open, as compensation for a half-day of training or inspections on Saturday morning, which facilitated Wednesday evening gatherings) and hosted receptions and other activities between local church communities and soldiers who also subscribed to that faith.

"[I]f you will consult my report that has to do with the action of the various chaplains[,] chaplains of the seventeenth, his will stand out. Both the correspondent of the New York paper and other news will at time carry a report of his actions. After the battle he was going over mountains, on foot mind you, all over the cockeyed island all the time that we were there preaching from 7 to 9 and more services a week. He work so hard and continuous all the time while there that his health broke and he was later declared unfit for combat (over) duty and was transferred out of a regiment of men who had come to love him because of what he was and still is - a true asset to the Chaplaincy. I don't know why he didn't get some decoration for his work on Attu during actions, but I do know that when the decorations were all given out that upon seeing some who got them for seemingly nothing at all. And to think that his name was not so much as mentioned didn't make just made >me< so mad that I could hardly stand it. It just made me so contemptably disgusted with the whole cockeyed affair that I haven't as yet so much as worn one single ribbon, metal, or decoration for combat action. And what's more I don't care a whole lot whatever I ever do if Chaplain Clarence J Merriman now of APO 960-75 station hospital doesn't receive some recognition, which beyond the any shadow of a doubt he definitely deserves.”

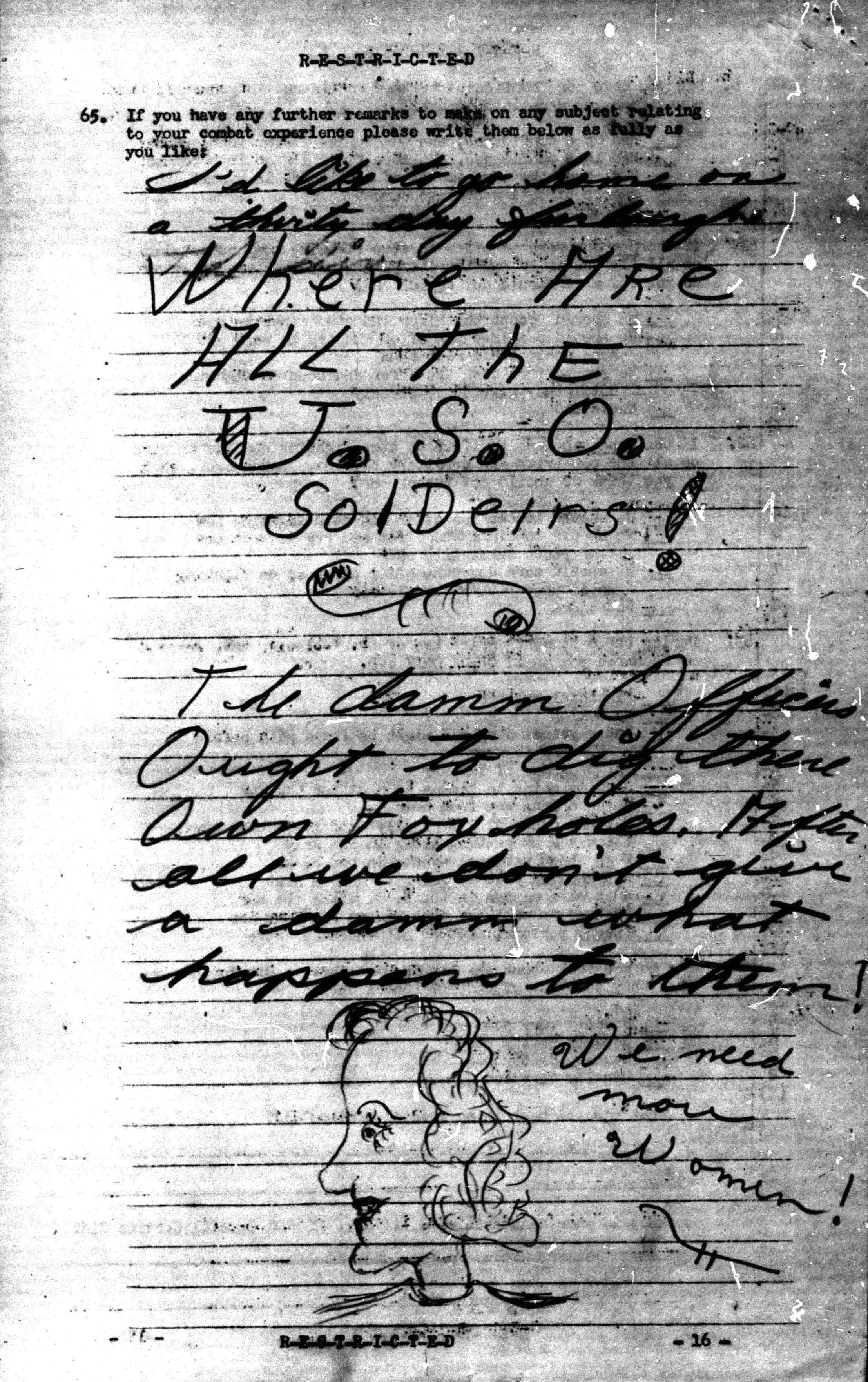

While the World War I-era army had eagerly partnered with many organizations, it sought greater control over these organizations and activities during World War II, both to increase program effectiveness and reduce factional infighting. Feedback from the Great War revealed a frustration with “the damn Y-man,” representatives of the Young Men’s Christian Association who often tied services to “preaching” that soldiers resented, making them reluctant to patronize the “Y’s” services.2 To ameliorate this, the army collaborated with the new USO, which, along with the Red Cross, largely tended to individual soldiers' off-post needs, while army services concentrated on maintaining morale and fitness for duty on post.

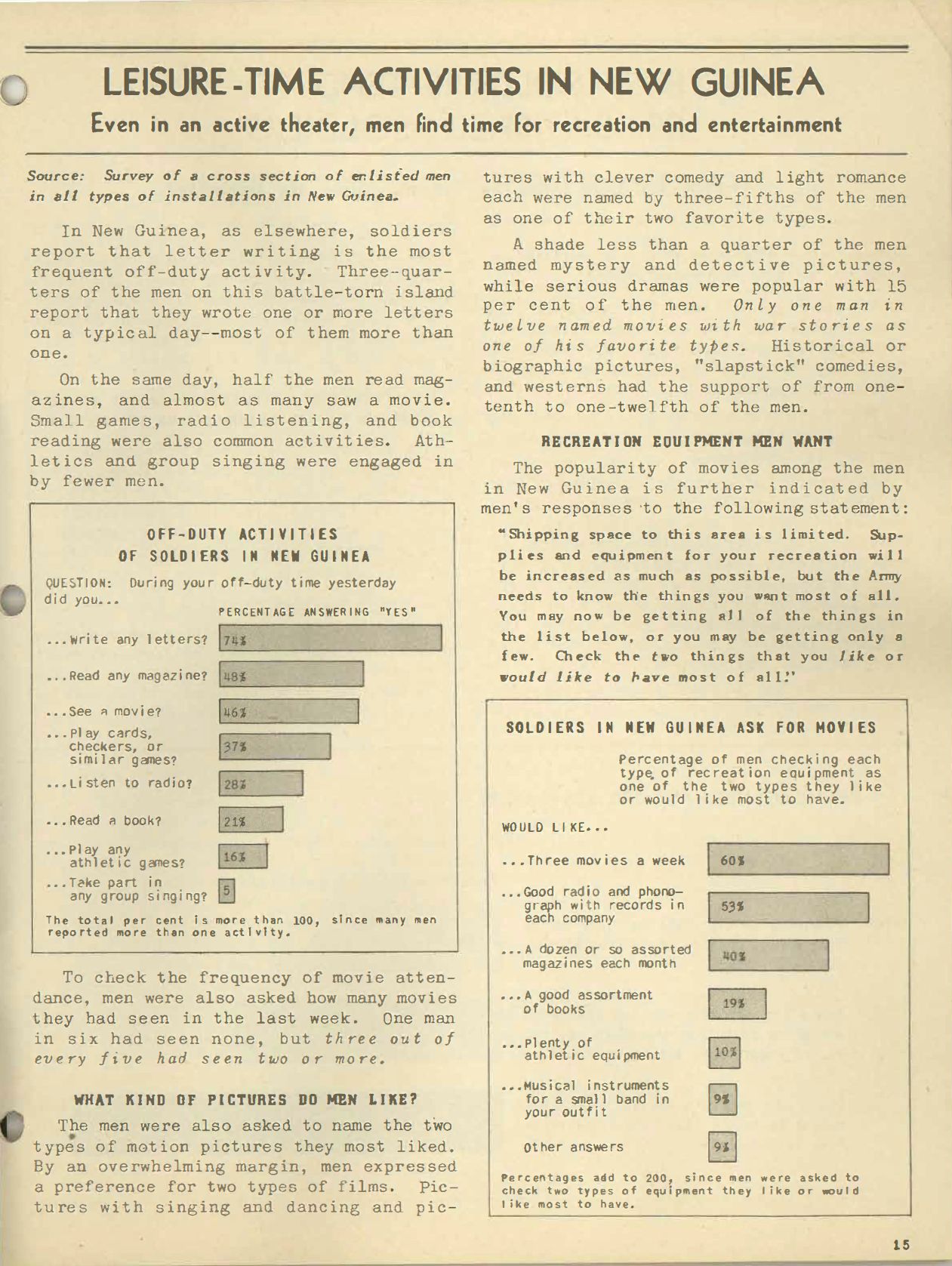

“Leisure-time Activities in New Guinea,” What the Soldier Thinks, no. 1 (December 1943).

The USO, which brought a number of separate organizations together under a single banner, provided over 800,000 books and 250,000 magazines, and distributed over ten million envelopes in just a single month. Letter-writing topped one list of preferred leisure activities compiled from troops in New Guinea, and receiving a letter or care package from home remained one of the best ways to boost morale, justifying the tremendous effort the army invested in postal units and efficient service. Mail gave soldiers reassurance that all was well at home, though letters sometimes brought bad news, including the infamous “Dear John” letters that ended relationships. While the USO brought many organizations under a larger umbrella, some, most notably the Red Cross continued to offer recreational activities and ran centers in many large cities that offered soldiers a safe, and vice-free, place to stay overnight while on leave.

On-Post Recreation & Contested Spaces

Despite the wealth of off-post recreational opportunities, soldiers spend most of their time on-post, making the army’s official programs an important part of soldier welfare and morale. This included construction of “service centers,” where off-duty soldiers could go to relax, read a magazine or newspaper, write a letter, or enjoy a cold Coca-Cola. The Post Exchange (commonly abbreviated “PX”) also offered a wide variety of refreshments, including candy bars and the ever-popular ice cream, which, while not exactly healthy, did not add too many pounds to soldiers who were exceptionally active. The PX also offered cigarettes for sale, and when soldiers deployed to the field, they received an issue in their daily rations—perhaps a nod to pacifying soldiers addicted to nicotine, but also a recognition that the worst health effects from smoking would not manifest themselves until long after a soldier had been discharged. Many prominent athletes smoked, some even doing so publicly between innings or rounds of a boxing match. Surveys included many basic marketing questions and asked soldiers what types of cigarettes and other items they would like to have stocked at their PX, whether the operating hours and locations were convenient, and which magazines they preferred to read, by title. Data on preferred film genres, types of music, and radio programs were similarly specific.

“USO Negro Servicemen's Dance and Reception, 99 Nichols Court, Hempstead, New York 10 June 1943. Billie Holliday, ‘Sweetheart of Jive,’ James C. Thomas, Director.” Courtesy of Univ. of Minnesota Libraries, DLS ID ya000085.

In many cases, the strictly segregated service clubs and theaters became contested sites for integration, as Black soldiers sought to use the larger, better equipped facilities reserved for White soldiers rather than the limited, or often simply unavailable, ones set aside for Black soldiers. In some cases, especially under the leadership of far-sighted commanders, clubs successfully integrated; however, racist White soldiers, most often from the South where Jim Crow was firmly established, typically resented these challenges to the color line and strictly enforced segregation, often resorting to violence to do so, confident that Black soldiers would shoulder the blame for any “riots” that resulted. Such was the case at Freemen Field in southern Indiana, when pilots of the famed Tuskegee Airmen attempted to integrate the base’s officer’s club but were charged with inciting a mutiny, even though their efforts served as a model of civil disobedience in the Civil Rights Era. As a result, the army often segregated its survey results as well, segregating data from White and Black units.

Food & Clothing

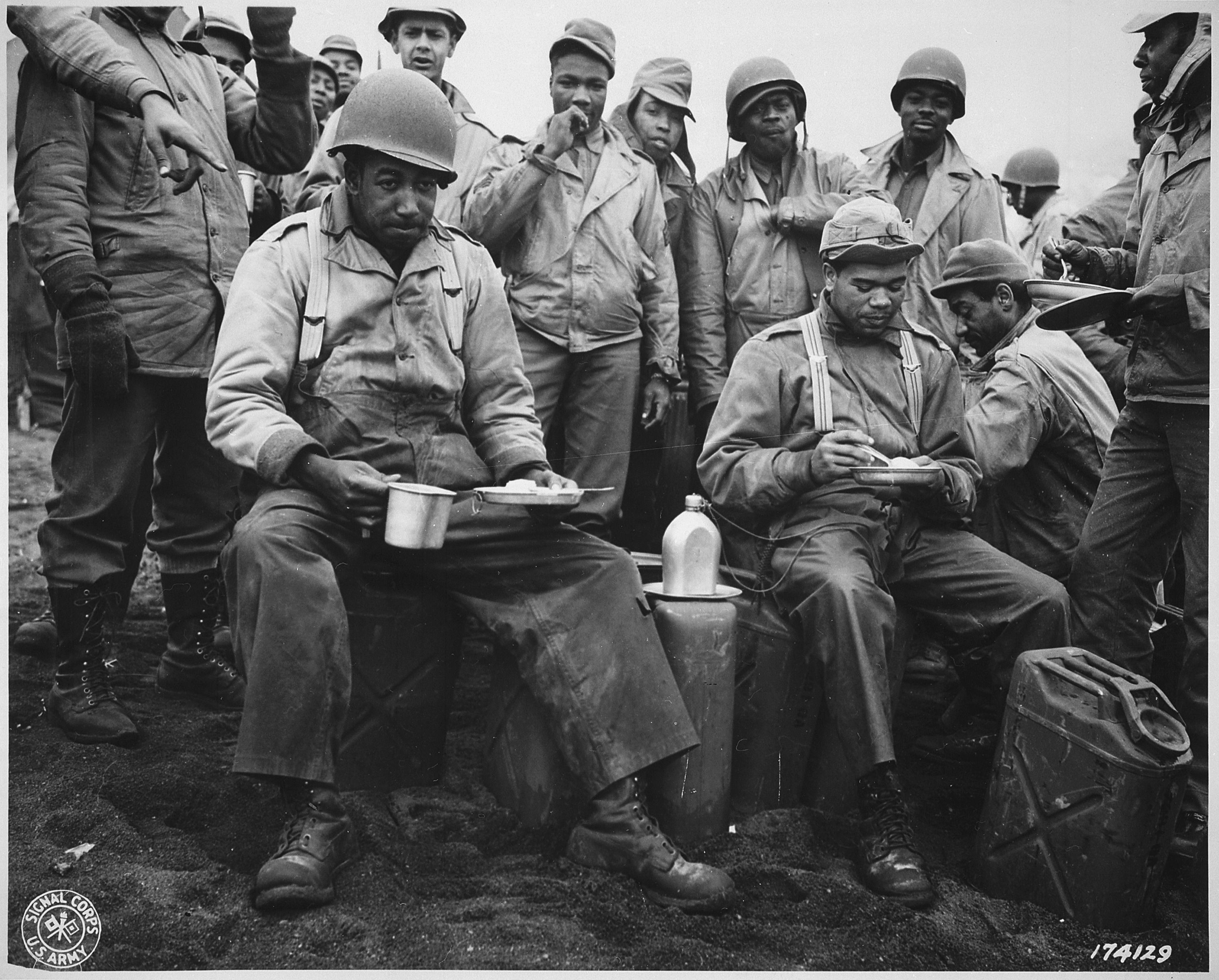

“A kitchen was set up along the beach for the...labor battalion unloading the boats. This picture shows a couple of the men enjoying a hot meal for a change. Massacre Bay, Attu, Aleutian Islands,” 20 May 1943. Courtesy of NARA, 111-SC-174129, NAID 531159.

The saying that “an Army fights on its stomach” proved literally and figuratively true during the Second World War, and the U.S. Army was generally better fed than most of its allies and adversaries, though remote locales and logistics interruptions were exceptions to that rule. Surveys collected data on what types of food soldiers preferred and, though quantities were usually generous, the quality varied greatly. Powdered eggs and dairy products were universally unpopular, sparking an almost obsessive quest for fresh items. The ubiquitous Hershey chocolate bar became almost a symbol of the G.I., though some varieties designed to withstand melting at high temperatures in tropical environments proved unpalatable. Units attached to British units tired quickly of “bully beef” issued through crown channels, and units across the Pacific grew to hate canned mutton procured in Australia. Fresh fruits and vegetables were as popular as they were rare. Good food not only led to good health, but also had a direct correlation on soldier and therefore unit morale.

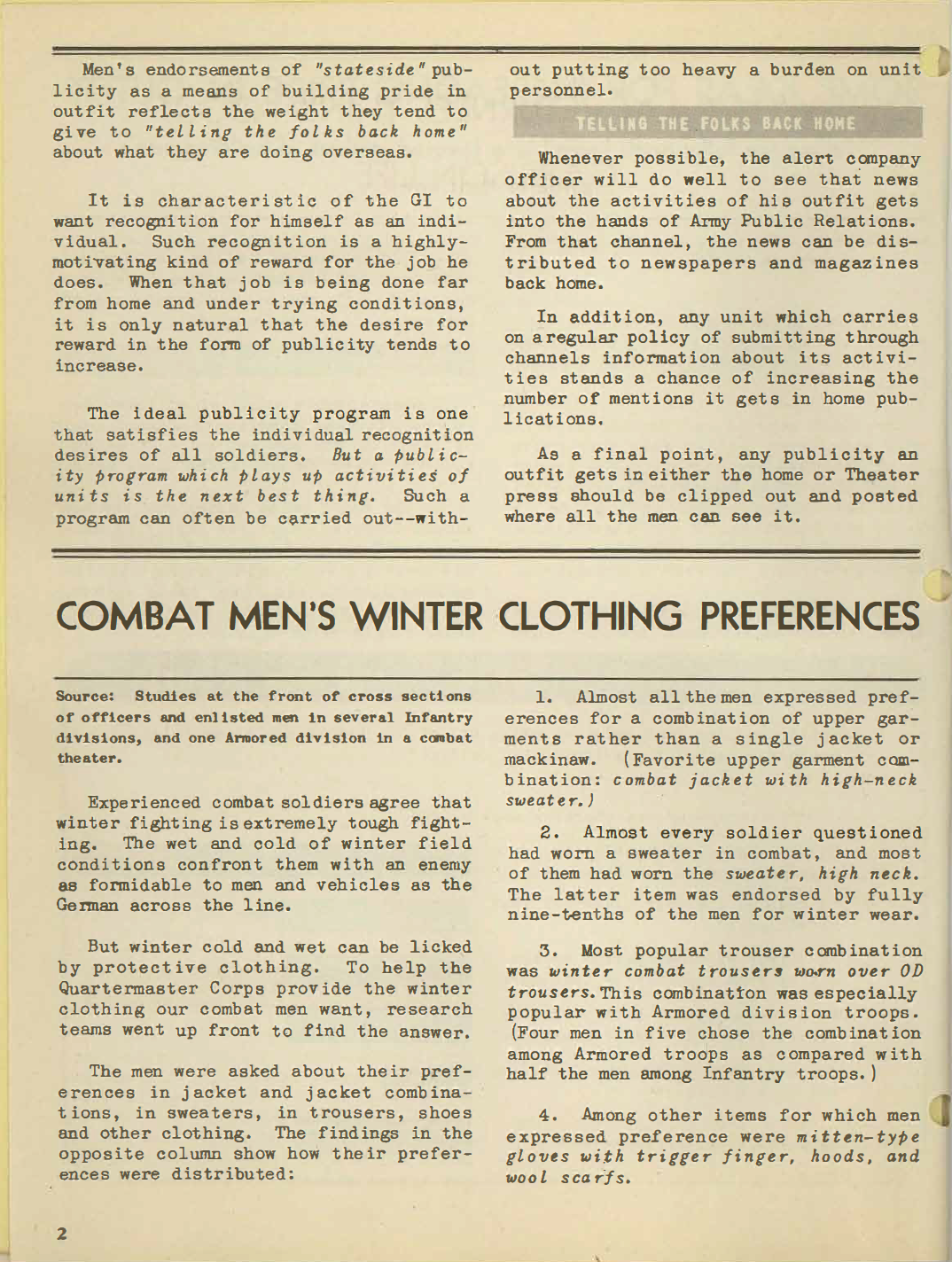

“Combat Clothing Winter Preferences,” What the Soldier Thinks, no. 13 (April 1945).

Once committed to combat, soldiers lived most of their lives outside in the elements, making protection from them of vital importance. The army sought information on which particular items of clothing the soldiers preferred, and which items performed best in different conditions. Given the wide range of climates and locales the army operated in—from the Alaskan Arctic to the jungles of the South Pacific and Southeast Asia—quartermasters had to develop and stock specialized equipment adapted to each. Rubberized boots, known as “shoepacks” helped alleviate trench foot and the popular high-necked wool sweater added an extra layer of insulation to whatever coats were available. “Jungle packs” included waterproof plastic liners that could keep socks and rations dry, and soldiers expressed a preference for ponchos instead of raincoats, as they could double as waterproof blankets or foxhole covers. The army solicited soldiers’ feedback on all of these items and others, to ensure that the equipment it issued was optimally adapted to each environment, and that soldiers had the best protection possible from the elements, keeping their spirits up.

Overall, the army’s expansive program of recreation and morale-bolstering services largely served its purpose, keeping the majority of soldiers ready to fight, even if there were still cases of drunkenness and debility from “VD.” Organized athletics provided team-building activities that increased unit pride and esprit de corps while also offering additional physical activity for soldiers whose occupations did not require it, such as clerks and mechanics. Scheduled matches, along with releases of the latest Hollywood films (many of which provided initial runs for on-base theaters), musical concerts, and radio broadcasts of heavyweight bouts gave soldiers engaged in the tedium of training or duty something to look forward to at the end of the day and opportunities to socialize with fellow soldiers. And dances, mixers, and tours offered ample opportunity for companionship with members of the opposite sex.

The army carefully tailored these programs based on soldier feedback and continued many of them through the Cold War and into the all-volunteer force of today. And the data collected provides detailed insight into the individual and collective preferences of the men and women inducted into service during World War II, and therefore into the larger society from which they were drawn.

Christopher M. Rein

Air University Press

Further Reading

Steve Bullock, “Playing for Their Nation: The American Military and Baseball During World War II,” Journal of Sport History 27, no. 1 (Spring 2000), 67–89.

James J. Cooke, American Girls, Beer, and Glenn Miller: GI Morale in WWII (University of Missouri Press, 2012).

Jeffrey C. Copeland and Xan Yu, eds., The YMCA at War: Collaboration and Conflict during the World Wars (Lexington Books, 2018).

Select Surveys & Publications

S-35: Trend Study and Special Services Facilities

S-133: Alaska Department

S-199: Winter Clothing II

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 1 (December 1943)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 8 (August 1944)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 9 (September 1944)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 13 (April 1945)

- Steve Bullock, “Playing for Their Nation: The American Military and Baseball During World War II,” Journal of Sport History 27, no. 1 (Spring 2000), 76.

- See Joel R. Bius, “The Damn Y Man in WWI: Service, Perception, and Cigarettes,” in Jeffrey C. Copeland and Xan Yu, eds., The YMCA at War: Collaboration and Conflict during the World Wars (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2018).

SUGGESTED CITATION: Rein, Christopher M. “Recreation & Welfare.” The American Soldier in World War II. Edited by Edward J.K. Gitre. Virginia Tech, 2021. https://americansoldierww2.org/topics/recreation-and-welfare. Accessed [date].