Readjustment & Postwar Life

The return of a soldier to civilian life ranks among the most difficult of challenges for both the veteran and the government that sent him to war.

While the United States government has never refused a pension to a discharged soldier wounded in service, this longstanding commitment counts as a bare minimum. Prior to World War I, if lawmakers in the US government recognized an obligation to help veterans with no identified disability, they did so principally by awarding civil service “points” to enhance their prospects for obtaining government jobs, or granting early or special access to land grant programs.

James McCutchen, Bounty Land warrant application, March 3, 1855, under the Act of March 3, 1855. Courtesy of The University of Tennessee Libraries (Knoxville, Tennessee), PID volvoices:15607.

A parcel of land can be considered a form of payment, one that a young country disposed to view the continent as open to settlement could bestow on veterans without incurring much financial cost. But land grants might also be regarded as something more than compensation: in an agrarian economy, land might be considered access to opportunity, an asset that would produce many returns. Notwithstanding these benefits, many veterans lobbied for compensation in the form of cash—the most fungible and immediately useful of assets, yet one that was frowned upon by generations of lawmakers as an unseemly degradation of the citizen-soldier ideal.

Like others who came before them, government officials planning for the postwar looked upon access to opportunity as superior to cash when considering the transition of soldiers back to civilian life. But farmland was no longer the principal form of security in an industrial US economy, leaving them without any direct precedent upon which to model their approach. Instead, for inspiration, they looked to Franklin Roosevelt’s social programs of the New Deal, as well as to opportunities traditionally offered to disabled veterans.

The G.I. Bill

"Veterans Prepare for Your Future thru Educational Training, Consult Your Nearest Office of the Veterans Administration," n.d. Courtesy of NARA, 44-PA-2262, NAID 515969.

Cobbling together various proposals into one omnibus bill, congressional sponsors passed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (popularly known as the “GI Bill”), a series of entitlements designed to enhance opportunities in a modern economy: reimbursement for education and vocational training; credit toward loans for a home or business; and up to one year of unemployment compensation for a veteran to settle into a new place, or reacquaint himself with an old one. In return, government planners aspired to assist—and ultimately benefit from—a growing and more prosperous middle class. Most of all, in passing the GI Bill, government officials hoped to avoid the turmoil of the previous war’s readjustment, when high unemployment dogged the country for several years.

The war was far from over when Franklin Roosevelt signed the GI Bill into law in June of 1944, before Allied victory in Europe or the Pacific. With those still in uniform preoccupied by war, unsurprisingly U.S. Army soldiers polled in October of 1944 professed to knowing little about the GI Bill. In a separate poll of only African American service members, Survey 144, conducted in August of 1944, army officials did not even pose the question, perhaps because the bill had passed only two months before.

Still, answers to other questions in these same surveys reveal that postwar planners understood well the changed nature of the World War II military force: most soldiers, including African American service members, lived in some type of city before service, and worked in skilled, semi-skilled, or unskilled jobs. They would not return home to a farm, forging their swords into ploughshares, as in the ancient example of postwar readjustment supplied by the Roman general Cincinnatus. Something other than agrarian life awaited the vast majority of them.

Exactly what was in store for discharged soldiers following the war could not be predicted on the basis of their experiences before it. In a variety of ways, service changed these soldiers. With few exceptions, they left home far behind, regardless of whether bound for wartime theaters abroad or stationed elsewhere in the United States. Even a soldier who never set eyes on an island in the Pacific or trudged through a snowy forest in Belgium returned from military service a changed man, usually with new skills, a new bearing, and perhaps carrying his own trauma as well.

Mustering out proved a task of enormous complexity—and an emotional ordeal in its own right, not least because of the overwhelming desire expressed by soldiers polled by the military to return home, and to civilian life, as soon as possible. Days following the German surrender (V-E day), the army asked all soldiers currently serving to list their length of service and number of dependent children in order to sort them for discharge, awarding each answer a set number of points. (The Navy, the lead branch in the ongoing Pacific War, could not yet plan for demobilization.) Unless a soldier’s work was deemed “essential,” the total number of points would determine priority for discharge.

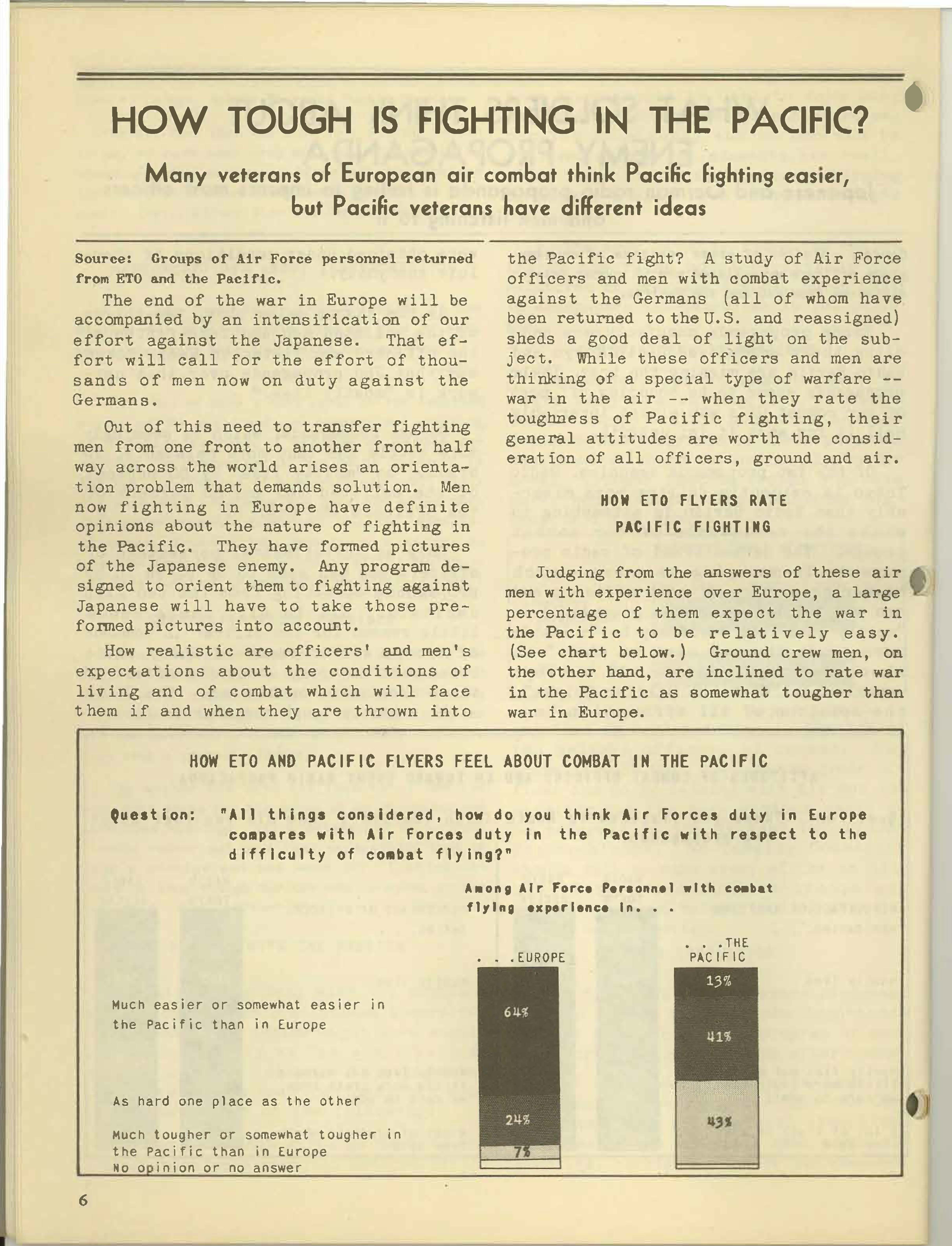

"How Tough Is Fighting in the Pacific," What the Soldier Thinks, no. 8 (August 1944).

Accordingly, the army launched a massive reshuffling of units based on points so that entire units could be discharged at once. Reasoning that the category of low-scoring men would be needed for an anticipated invasion of Japan, the army sent many of these soldiers home to enjoy a brief leave before redeployment to a dreaded mission, one which American planners anticipated would come at painful cost. In a remarkable turn of history, the United States ended the war in the Pacific by dropping atomic bombs on two cities in August of 1945. Rather than pay for shipping their “low scorers” back to Europe, the army mustered most of them out while they enjoyed leave. High-scoring soldiers stationed elsewhere chafed at this all too typical fate for the best laid military plans. This was one irritant among many for the soldiers who launched waves of protests throughout 1946 to show disgust with the slow pace of demobilization.

Discharge itself was a jarring experience, and potentially a source of anguish for men who had grown accustomed to a new life and bonded to new friends. To facilitate the process, soldiers were sent to domestic “separation centers”—including six posts dedicated exclusively to the discharge of members of the Women’s Army Corps (WACs). While at the separation center, soldiers received vocational counseling, an important medical exam (which might serve as the basis for a disability claim), and a pitch to re-enlist. The last day at the center entailed a departure ceremony, the final act of which was to award discharge papers, a record of service denoting the terms of separation, honorable or dishonorable—or “blue,” an administrative discharge usually given to soldiers found to engage in same-sex intercourse, or African American soldiers who protested the segregation of the military while serving in it. Anything other than “honorable” discharge disqualified a veteran from the GI Bill, and could often imperil job prospects as well.

Once holding discharge papers, a soldier, though still in uniform, was officially a veteran.

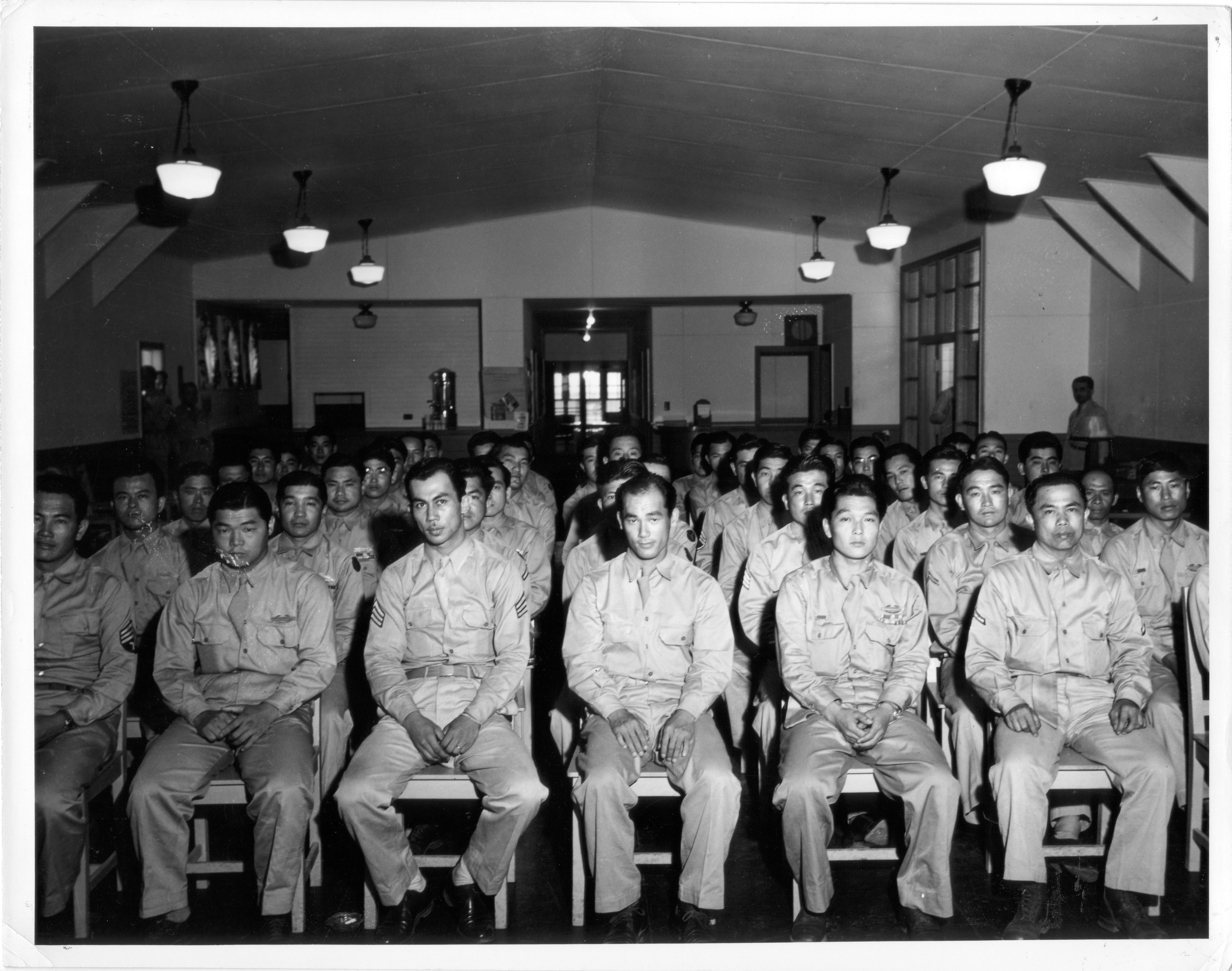

"Oahu, T. H. The first 48 veterans to be discharged from the Army under the point system, seated here, are waiting for their certification at the Separation Center. All but two are members of the famous 100th Battalion, 34th Division, which saw plenty of action in Italy and France," 23 May 1945. Densho Digital Repository. Courtesy of Courtesy of the Seattle Nisei Veterans Committee and the U.S. Army, OID ddr-densho-114-31.

A Strange Return to a Country Reborn

A returning service member bound for home, though a common enough sight, was a deeply evocative moment—and, for this reason, an attractive plot device in literature and film, perhaps most memorably in the opening scenes of the 1946 film classic, The Best Years of Our Lives. Somewhat surprisingly, it was common and accepted for discharged soldiers to express anxiety before returning to a place that had changed while they were away, and to people whom separation had made unfamiliar. A small town in the rural south was now without about 15 percent of its prewar population, with many of its migrants bound for sunbelt states like California, where defense production work boomed. African Americans left for northern cities, inaugurating a “second Great Migration,” the magnitude of which would far eclipse the first.

Wartime changes transformed the home front, even behind the closed doors of family life. Six million women entered the paid labor force for the first time during the war, joining the roughly 13 million already working for wages. These new entrants to the wage labor market were encouraged to return to housework once the war was over, an expectation that did not always sit comfortably with those asked to fulfill it. A surge in marriages at the start of war was followed by a spike in divorces immediately after it. Housing shortages were pervasive, especially in areas of the defense industry. A younger, unmarried veteran returning home could easily find himself living with his parents for longer than anticipated; an older married one might return to a wife who had forged a new sense of independence while he was gone. These and many other potential points of strain led author Maxwell Droke to advise veterans that their transition to civilian life would be easier “were it not for two things: your family and friends.”

For African American veterans, readjusting to home involved a third obstacle: home. Segregation, institutionalized racism, and pervasive bigotry eliminated a great deal for them—including many opportunities made available by the GI Bill, which delegated different benefits to individual states or private institutions to implement according to their preferences, which often excluded Black beneficiaries. Worse still, African Americans who used their service in war to lay claim to full citizenship at home faced grave danger.

After Maceo Snipes, a veteran living in the state of Georgia, became the first African American in his county to successfully cast a vote in a Democratic primary, a White veteran shot him. (Snipes died from his injury days later at a hospital, for want of a blood transfusion during a time when blood donations were also segregated.) Claiming self-defense, the man who killed him was never charged. The unprosecuted murder elicited a letter to the Atlanta Constitution from a young Morehouse College student. “We want and are entitled to the basic rights and opportunities of American citizens,” wrote Martin Luther King Jr., offering a glimpse of what would become his life’s work, and an intimation of its tragic end.

The difficulties faced by African American veterans were fundamentally different from those of other returning soldiers, but no veteran went unburdened, or returned unchanged. The GI Bill eased the transition of many, if only in staggered and uneven fashion. Except for unemployment compensation, veterans eligible for the GI Bill typically waited before using benefits. Many took several years before applying for the credit-backed housing benefit, avoiding the chaos of wartime housing. A review of surveys such as Survey 144 or 159 might result in surprise over the low numbers expressing an interest in pursuing formal education after their service, but in fact most veterans who used the education title applied it toward vocational training.

In all, with or without particular GI Bill benefits, veterans faced a daunting task. As the remarkable social experiment of the largest conscripted military force in US history came to an end, a new country emerged in its wake, with readjustment of former service members furnishing a dramatic example of a “daily plebiscite”: the encounters and experiences of ordinary people which, as French historian Ernest Renan argued, collectively forge the life of a nation, and ultimately determine its fate.

Kathleen Frydl

Independent Scholar

Further Reading

Benjamin Cushing Bowker, Out of Uniform (W.W. Norton & Company, 1946).

Jennifer Brooks, Defining the Peace: World War II Veterans, Race, and the Remaking of the Southern Political Tradition (University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

Lizabeth Cohen, A Consumer’s Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America (Vintage Books, 2004).

John Egerton, Speak Now against the Day: The Generation before the Civil Rights Movement in the South (University of North Carolina Press, 1995).

Kathleen Frydl, The GI Bill (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Michael J. Hogan, A Cross of Iron: Harry S. Truman and the Origins of the National Security State, 1945-1954 (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Neil R. McMillen and Morton Sosna, Remaking Dixie: The Impact of World War II on the American South (University Press of Mississippi, 1997).

Joanne Meyerowitz, Not June Cleaver: Women and Gender in Postwar America, 1945-1960 (Temple University Press, 2016).

David R. B. Ross, Preparing for Ulysses: Politics and Veterans During World War II (Columbia University Press, 1969).

Select Surveys & Publications

S-106: Post-War Army Plans (Officers and EM)

S-144: Post-War Plans of Negro Soldiers

S-159: Soldiers’ Knowledge of GI Bill of Rights and Post-War Education Plans

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 8 (August 1944)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 9 (September 1944)

What the Soldier Thinks, Post-War Plans of the Soldier (Special Issue, n.d.)

SUGGESTED CITATION: Frydl, Kathleen. “Readjustment & Postwar Life.” The American Soldier in World War II. Edited by Edward J.K. Gitre. Virginia Tech, 2021. https://americansoldierww2.org/topics/readjustment-and-postwar-life. Accessed [insert date].

COVER IMAGE: "When Do I Go Home? Demobilization Program," Newsmap 4, no. 23 (24 September 1945). Information & Education Division, Army Service Forces, War Department. Courtesy of NARA 26-NM-4-23b, NAID 66395368.