The Home Front

In the beginning of World War II, the United States was able to ramp up war preparedness at a measured pace while it considered itself a neutral country. Much of the Pacific fleet of the US Navy was docked in the American territory of Hawai’i when the Japanese military launched a strike against local bases, resulting in over 2,400 deaths and substantial ship damage. Most Americans were subsequently startled to hear this news of war on the home front through radio bulletins or word of mouth. In a famous speech a day later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proclaimed December 7, 1941, as a “date which would live in infamy” and returned Japan’s declaration of war.

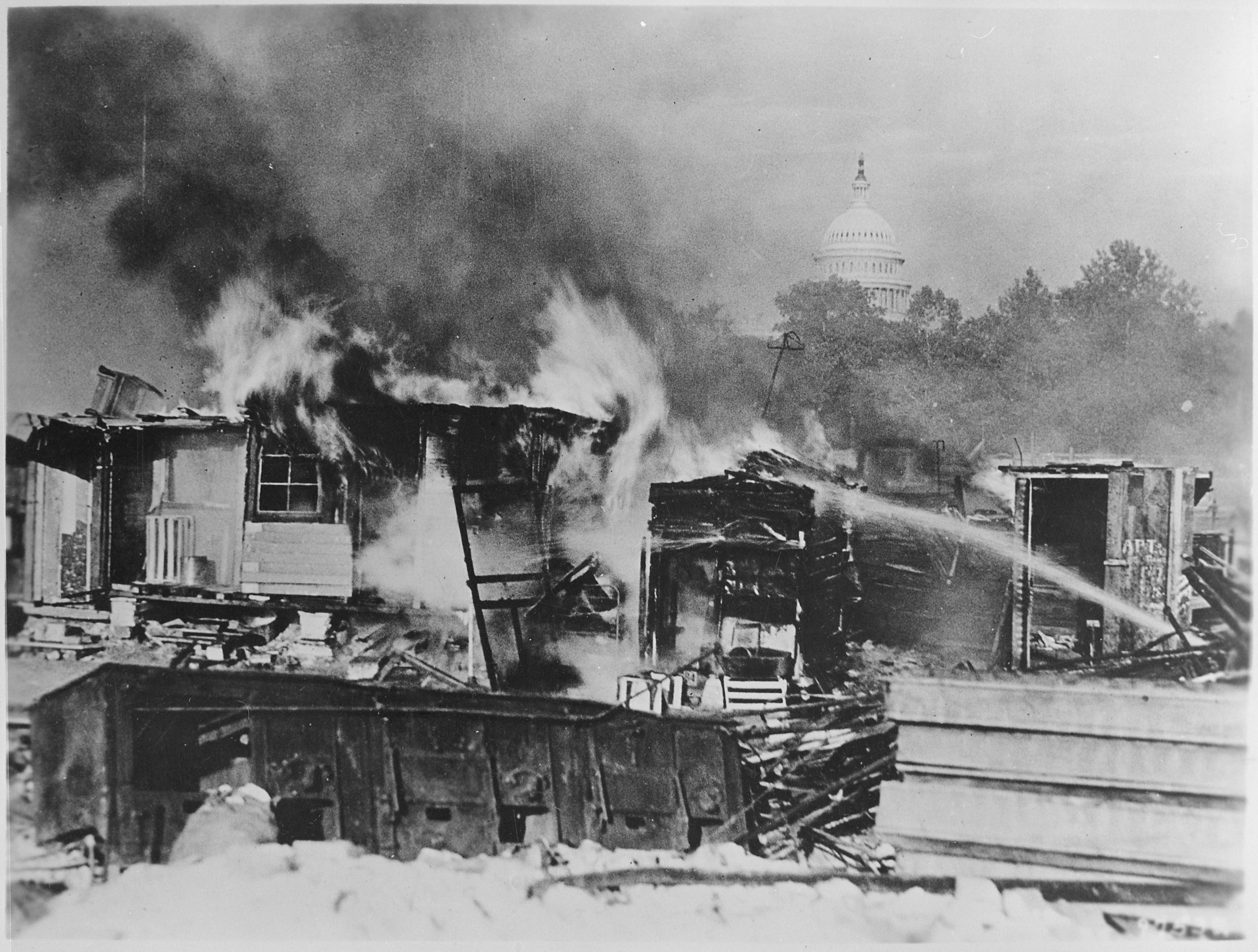

Yet, support of US military involvement was not immediate and without resistance. Looking back one decade prior, a group of World War I veterans described as the “Bonus Army” marched on Washington during the Great Depression in hopes of collecting early compensation for their service overseas, only to have their protests met with violence by soldiers and police dispatched by President Herbert Hoover.1

"Shacks, put up by the Bonus Army on the Anacostia flats, Washington, DC, burning after the battle with the military," 1932. Courtesy of NARA, Z-030, 111-SC-97532, NAID 531102.

Leading into World War II, some Americans consequently displayed distrust towards the US military establishment or sought to avoid the brutal realities of another conflict in Europe, while others were proponents of white supremacy and even sympathized with the Nazi agenda. While the federal government sought to bring the full diversity of Americans together in support of the Allied cause, this proved challenging for a number of reasons. Not only were the US armed forces and civilian manufacturing sectors ill-prepared to join a major conflict, inequities embedded within American society continued to divide the home front and threaten the war effort.

The Selective Service System

"Build for your Navy! Enlist! Carpenters, machinists, electricians etc." Works Projects Administration Poster Collection. Photographer R. Muchley. Courtesy of Lib. of Congress, control no. 98517380.

Disregarding widespread hesitancies towards foreign intervention, Congress instituted the country’s first preemptive peacetime draft through the Burke-Wadsworth Act in September 1940, which initiated the Selective Training and Service program. This bill was particularly contentious due to the backlash against creating a standing, professional army and extension of active-duty deployment.

While fewer than 200,000 people served in the US Army in 1939, that number quickly grew to nearly 1.5 million troops by 1941, with over 12 million joining the armed forces throughout the course of the conflict. Initially, only American men between the ages of 21 to 35 were required to register with the Selective Service System. This range was controversially expanded to the ages of 18 to 64 after the US entered World War II, as shortages motivated the military to transition away from voluntary enlistment. President Roosevelt particularly sought to cultivate an army of “citizen-soldiers”: everyday Americans who were trained and ready to defend their country. These measures helped frame military service as a patriotic duty exercised through the draft, similar to civilian mobilization efforts on the home front as the war got underway.

Channeling Manpower

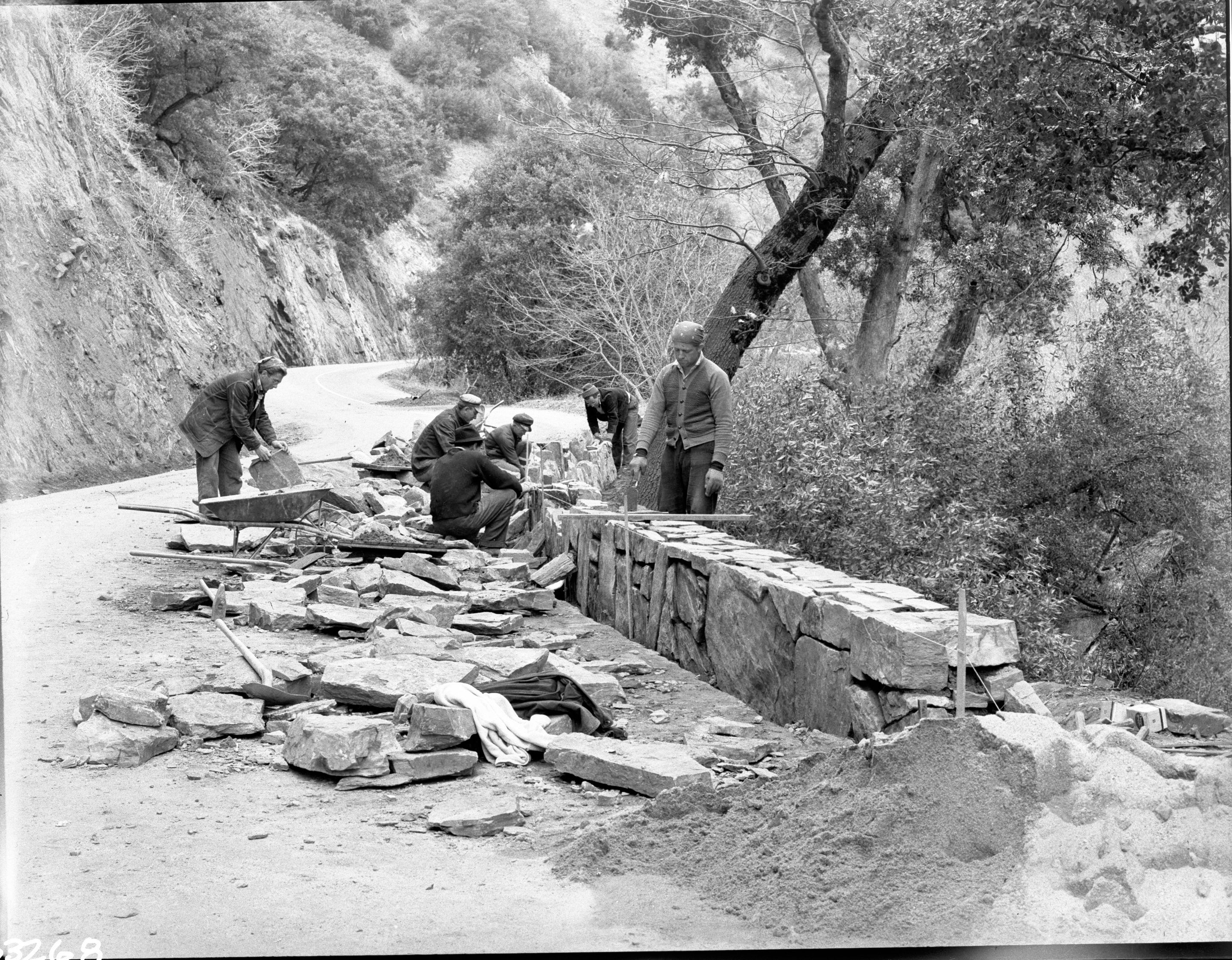

Wary of being drafted into the army and being sent to the frontlines of battle, some men signed up in recruitment offices of other branches of the military before they were called up for mandatory service. By enlisting, they believed that they could receive a better assignment and improve their standing in the system. On the other hand, conscientious objectors opposed the war on religious or moral grounds and went on to serve their country through the Civilian Public Service, which continued many of the domestic public works campaigns set in place during the New Deal. However, the FBI also investigated a significant number of cases of “draft dodging,” with around 5,000 men being imprisoned for their alleged evasion of military service.

"Construction, rock wall construction by conscientious objectors, Civilian Public Service (CPS) men," Amphitheater Point, Sequoia National Park, Tulare County, Cal., 17 January 1945. Photographer Irv Kerr. Courtesy of National Park Service, AssetID b62b2ae0-9fa7-49dc-8364-9f4988169f75.

Furthermore, some men qualified for exemptions based on their family circumstances, educational status, or a disability, and instead contributed to nationwide efforts on the home front. Others worked in essential jobs like farming or the defense industry and were therefore permitted a draft deferment, though this allowance often exacerbated tensions between soldiers and civilian workers as the conflict progressed. And while only men were subjected to the expanded conscription program, over 350,000 women also volunteered to serve in uniform. They entered female divisions like the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WACs) and Navy Women’s Reserve (WAVEs), and served in roles from pilots and nurses to codebreakers while deployed both domestically and overseas.

Following the process of conscription or enlistment, newly inducted servicemembers reported for basic training on home front military bases across the country, which were either modernized or newly constructed to fulfill the demands of this expanded military infrastructure. Local communities often experienced an economic boom, with businesses emerging to offer goods and services catering to the war mobilization effort. However, these also became complicated spaces of convergence, as resentments stemming from disapproval of soldiers’ conduct and racism provoked tensions with local civilian communities, which frequently played out in disputes over women and violence against Black soldiers.

Attempting to mitigate these social strains between the military and civilians, charitable agencies like the United Services Organizations (USO) sought to boost morale and keep the GIs’ free time contained by providing in-house entertainment and hosting alcohol-free events like dances. Civilian groups like the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and American Red Cross also coordinated educational programs, medical supplies, and care packages, while post exchanges (PX) were set up on the bases to provide the troops with supplies and sundries.

America at Work

Echoing the military’s rapid mobilization, the defense industry also required substantial modernization at the outbreak of World War II. After some initial resistance, private factories that produced civilian goods like cars were converted to create planes, tanks, guns, ammunition, and military supplies. Attempting to counteract discrimination in these new jobs, civil rights activists lobbied President Roosevelt to establish the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) in 1941. The War Manpower Commission was subsequently created in April 1942 to manage federal policies outside of the military, from the defense industry and agriculture to hiring practices.

As a result of these efforts, civilians remaining on the home front during World War II benefitted from new professional opportunities and often migrated to areas of the country that offered wartime production jobs, known as “boomtowns.” This rapid process of industrialization provided regional development and resources, as well as increased potential for social mobility. Women were especially able to enter the workplace in record numbers, with approximately 6 million serving in civilian jobs such as Women Ordinance Workers, popularly known as “WOWs” or “Rosie the Riveters” during World War II.

However, these female workers continued to face sexism, often receiving unequal pay and fewer opportunities for career advancement than their male counterparts. Their home front experiences similarly echoed the discrimination that women frequently faced in the military.

Under Threat

Labor disputes also remained an issue throughout World War II, with anti-strike legislation significantly impacting war workers who advocated for further rights and higher compensation. Additionally, tensions between soldiers and civilians increased as the war progressed and the need for military personnel became more acute. Servicemembers were especially reminded of the relative safety of American domestic life when they were sent home on furlough, and sometimes lamented the better conditions the war workers experienced and their protections from being drafted.

While military experiences put young Americans from across the country into contact with each other for the first time, segregation remained in effect throughout the home front and military during the course of the war, with discrimination against African Americans impacting both their military assignments and safety on home front bases. Racism similarly affected Japanese Americans, who experienced wartime human rights violations in the form of forced relocation and incarceration, after unjustly being deemed “enemy aliens.” After declaring war on Japan, the US government imprisoned over 120,000 people from this community in concentration camps, spurring resistance and lawsuits against these inhumane incursions on civil liberties.

Furthermore, unrest devolved into racial violence in 1943 across cities like Los Angeles, Detroit, and New York, in light of mounting resentment towards domestic disparities and perceptions towards wartime contributions. White police officers and active duty servicemembers violently targeted civilians from Mexican, Filipinx, and African American communities, resulting in the deaths and injury of hundreds of people. News coverage branded these incidents as “race riots,” further fueling white supremacist narratives and placing blame on civilians rather than the perpetrators of violence from within the military.

"Violence erupts during the Zoot Suit Riots in Los Angeles (Calif.)," [1943]. Los Angeles Daily News Negatives. Courtesy of Dept. of Special Collection, UCLA, ID edu.ucla.library.specialCollections.losAngelesDailyNews:43, uclamss_1387_b64_29765-2.

Managing a United Front

“'We'll have lots to eat this winter, won't we Mother?' Grow your own can your own." OWI Poster No. 57. 1943 - O-520465. Artist Alfred Parker. Courtesy of Hennepin County Library Digital Collections, ID MPW00250.

Attempting to counteract the discord and inequities on the home front, the US government encouraged Americans to “pull together” as part of their patriotic duty to win the war and defend the world against encroachments on democracy. Wartime propaganda and public opinion campaigns helped rally support for the Allied war effort, but also spurred animosity towards the Axis Powers and immigrants from those countries. Music and movies produced during World War II further reflected the sentiments and values of the times. Food and goods were rationed to divert supplies to the military, and "victory gardens" became a way for Americans to patriotically grow their own produce. Scrap drives were mobilized to conserve materials and increase a sense of civic responsibility, while war bonds were sold to encourage civilians to invest in funding the military's needs. Many Americans also became involved in volunteer civil defense organizations by learning how to administer first aid, fight fires, and spot enemy planes.

Those remaining at home kept in touch with their loved ones and lifted the spirits of soldiers overseas by sending letters. V-mail often arrived with blacked out lines of censorship, though GIs increasingly learned to omit classified information about their assignments. The censors were particularly careful to obscure any strategic information that could be intercepted by Axis forces and used to their advantage.

Home front families especially feared receiving a Western Union telegram informing them that a loved one had been killed in action or taken as a prisoner of war. Civilians followed news about the conflict by listening to the radio, including President Roosevelt’s regular “fireside chats.” They also read newspapers and consumed newsreels at local movie houses to keep informed. However, this news coverage was carefully reviewed by the US government through the Office of War Information, and journalists were held to a wartime code of ethics for maintaining morale through their reporting.

Homebound

President Roosevelt’s death in April 1945 came as a shock to the country, leaving Vice President Harry S. Truman to close out the war. The American public went on to celebrate Germany’s surrender on V-E Day (Victory in Europe) in May 1945. While the US braced for a bitter final push in the Pacific, the atomic bomb—developed through the Manhattan Project and tested in the Los Alamos Laboratory on the home front—cut the war short through its horrific destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. V-J Day (Victory over Japan) subsequently came with widespread jubilation to many Americans, as Japan surrendered soon after in September.

As the surviving soldiers ended their deployment overseas, they came back to their hometowns as changed men and women. Many returned to fanfare, with patriotic parades and joyous homecomings. Others carried visible wounds and intangible scars from war, that their families then experienced in turn. Some struggled with returning to civilian life, but many male veterans eventually displaced women in their wartime jobs and continued to grow their families during what became known as the “Baby Boom.” Some believed that contributing to the workforce was no longer a right that the women were entitled to after the war.

The troops also often rode home from their battlefield experiences into colleges across the country on the GI Bill, expanding their education and bringing worldly knowledge back to the home front. Yet, Black veterans were frequently excluded from the same service benefits that their White male counterparts received. The war nevertheless significantly challenged US social order and racial hierarchies, paving the way for the African American movement for civil rights, women’s rights, and related struggles, as an extension of the freedom that the United States was fighting for overseas. Overall, World War II created a generation of citizen-soldiers and engaged civilians alike, changing the American home front forever through its total warfare.

Erica Fugger

Rutgers University - Newark

Further Reading

Paul Dickson, The Rise of the G.I. Army, 1940-1941: The Forgotten Story of How America Forged a Powerful Army Before Pearl Harbor (Grove Atlantic, 2020).

John W. Jeffries, Wartime America: The World War II Home Front (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018).

William L. O’Neill, A Democracy at War: America’s Fight at Home and Abroad in World War II (Harvard University Press, 1995).

G. Kurt Piehler and Sidney Pash, eds. The United States and the Second World War: New Perspectives on Diplomacy, War, and the Home Front (Fordham University Press, 2010).

Studs Terkel, ”The Good War”: An Oral History of World War II (The New Press, 2011).

Allan M. Winkler, Home Front U.S.A.: America During World War II (Wiley, 2012).

Select Surveys & Publications

PS-V: Attitudes toward Civilians

S-47: Shenango Study

S-132: Rotation Study

S-133: Alaska Department\

SUGGESTED CITATION: Fugger, Erica. “The Home Front.” The American Soldier in World War II. Edited by Edward J.K. Gitre. Virginia Tech, 2021. https://americansoldierww2.org/topics/the-home-front. Accessed [insert date].

- Paul Dickson, The Rise of the G.I. Army, 1940-1941: The Forgotten Story of How America Forged a Powerful Army Before Pearl Harbor (New York: Grove Atlantic, 2020).

COVER IMAGE: "The United States We Live in," Newsmap 4, no. 27 (22 October 1945). Information & Education Division, Army Service Forces, War Department. Courtesy of NARA, 26-NM-4-27b, NAID 66395380.