Assignment & Promotion

Wants & Needs

The man who donned the US Army uniform during World War II became a tiny part of a vast war machinery that grew explosively through 1945. The army numbered fewer than 200,000 servicemembers in 1939 but counted more than 8.2 million in its ranks at the war’s end. More than two-thirds of that expansion occurred between 1940 and 1943. Army leaders constructed systems that worked well enough to manage expansion and its attendant growing pains, but they did not work perfectly. Many servicemembers found success in these systems and fulfillment in their assignments. Others, unable or unwilling to see the big picture, remembered the friction.

Efficient manpower management posed problems for the organization and the individual alike. The army had to select people who met minimum standards, assign them jobs, train them, allocate them to units, and promote the most deserving. It also had to continually adapt its human resource systems to meet evolving needs. Individuals cared more about getting a “square deal” or a “good break,” but what they wanted and what the army needed did not always match. Moreover, many servicemembers defined themselves as temporary “citizen-soldiers” to whom the Old Regulars’ ways should not apply. They chafed against the army’s traditions, social stratification, authoritarianism, and hidebound caste culture as a result. Ultimately, soldiers’ satisfaction depended greatly on harmony between their wants and the army’s needs, and the perceived fairness of their immediate organizations.

“You May Be Eligible for the Army Specialized Training Program,” Newsmap 2, no. 3 (10 May 1943). Courtesy of NARA, 26-NM-2-3b, NAID 66395129.

The Officer-Enlisted Divide

If I Were the C.O….," What the Soldier Thinks, no. 7 (July 1944).

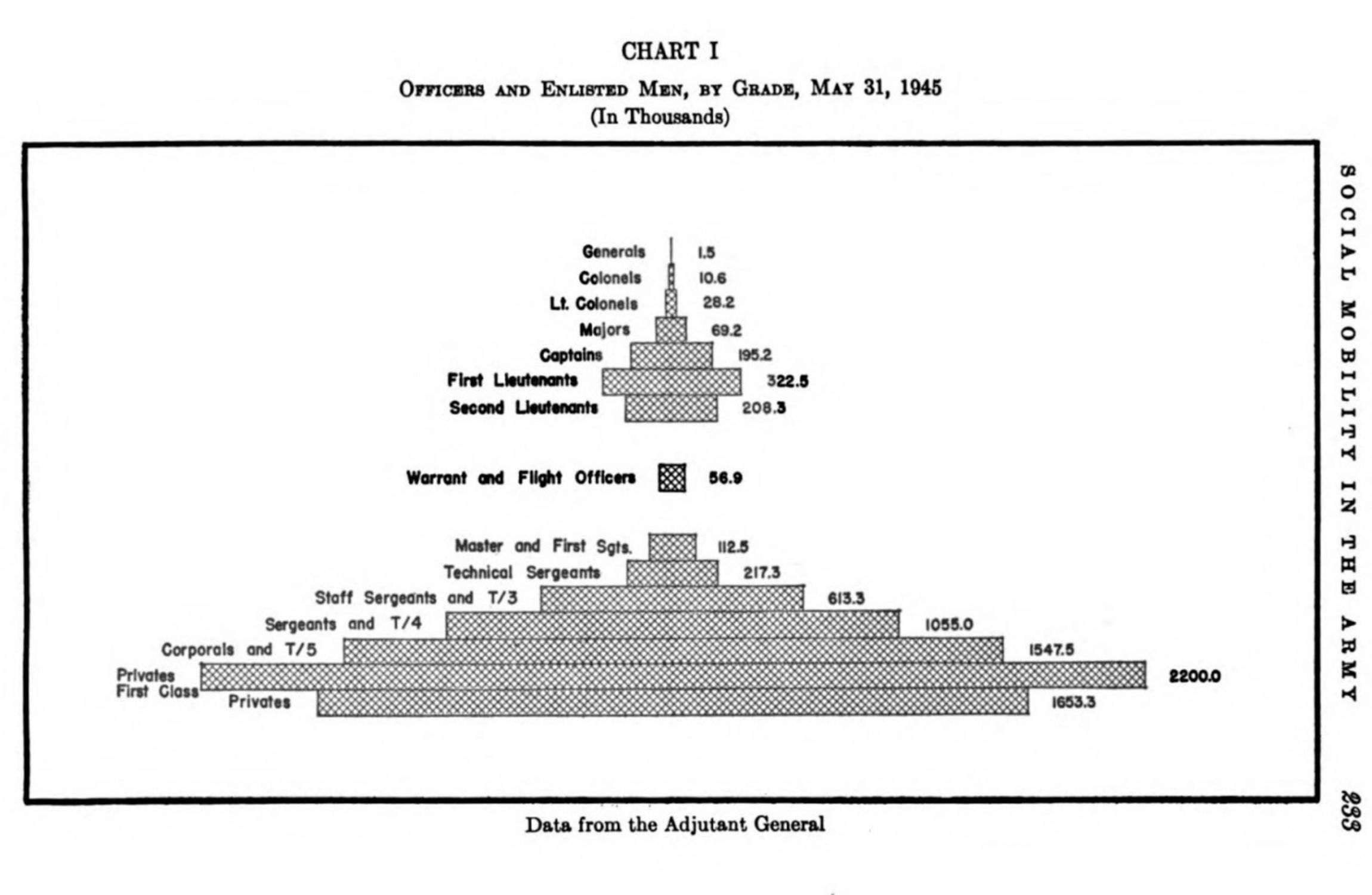

Distinguishing between officers and enlisted men is necessary because selection, assignment, training, and promotion systems differed by group. The army’s structure during WWII can be illustrated as two triangles, one larger than the other and each subdivided into layers, representing the service’s “castes.” Officers filled the smaller triangle, enlisted men filled the larger, and a “yawning social chasm” separated them (TAS, vol. II, 56). Generals and senior non-commissioned officers, or “noncoms,” occupied the tops of the officer and enlisted triangles, respectively. Lieutenants and privates inhabited the bases. Similar triangle pairs structured the Women’s Army Corps, the National Guard, and the Army Air Forces, though their proportions differed. Normally, officers led units and planned, while enlisted men performed specific duties. The former also enjoyed greater privileges than the latter, much to the chagrin of enlisted men. This social gulf did not reflect the structures to which White, male Americans were accustomed. Many enlisted men desired more respect and for their officers to be “regular guy[s] with the boys” (“If I Were the C.O….,” WST, no. 7 (1944), 2)). These classless ideals cut against the army’s traditional hierarchies. Unresolved tensions in officer-enlisted relations could create morale problems.

Enlisted Personnel: Accessions

All enlisted men experienced standard reception, sorting, and training processes. The enlisted man’s military career typically began at a local induction center with physical and psychological screenings. If he passed, he would move on to a reception center. There he underwent further physical examinations, sat for an interview, and completed the 150-question Army General Classification Test (AGCT). These mechanisms determined his job assignment, which was also known as a military occupational specialty (MOS). Adaptation to army life began at these temporary way stations. Wearing a freshly issued uniform, the new enlisted man learned how to salute, make his bed, and “hurry up and wait” while enduring calls of “you’ll be sor-ree” from older soldiers. Adapting to this unfamiliar culture and its traditions could be challenging.

“Lt. B. Holmes instructing cadres in the art of parry and long thrust in bayonet practice. Left to right: T/Sgt. Leroy Smith, Pvt. George W. Jones, and Sgt. Leo Shorty, look on,” November 1942. Courtesy of NARA, 111-SC-147979, NAID 531140.

Within days or weeks, the new soldier moved on to a training center aligned with his job and unit assignment. Subsequent experiences varied by camp or fort (of which there were 242 by 1945), by force affiliation (Army Ground Forces, Army Service Forces, or Army Air Forces), and by year of induction. Training for the ground and service forces, where the bulk of men were assigned, shared two phases. The first was “branch immaterial” and concentrated on military courtesy and physical fitness. The second prepared men to perform their specific jobs. Army Ground Forces (AGF) training included a third phase in which armor, artillery, and infantry elements exercised together as combined-arms teams. Before 1944, men usually learned their trade over a year as part of a unit. From 1944 on, men trained in their specialties for between eight and seventeen weeks before shipping out as individual replacements.1 The replacement system counteracted combat attrition, but often at the expense of unit cohesion and the individual’s well-being.

Enlisted Personnel: Job Assignments

Job assignment was a major factor in any given soldier’s satisfaction with the army. Volunteers could select their branch of service. They naturally reported higher levels of satisfaction. However, volunteerism shunted a large percentage of high-quality men away from the combat arms. For instance, a mere 5 percent selected the Infantry or Armored Force while the vast majority selected the Air Corps.2 The army consequently stopped accepting draft-age volunteers at the end of 1942. Selectees, who comprised most of the army’s manpower, had less control over their destinies. Their assignments were products of pre-existing skills, AGCT results, and luck. The reception center interview and AGCT supposedly identified skills from civilian life and general aptitude, or “trainability.”3 Ideally, this sorting process sped up mobilization by filling demands for specialists with men from related civilian occupations.4 In reality, mismatches and disappointment were not uncommon.

Because the AGCT purportedly identified potential for leadership and technical work, high scores opened opportunities such as officer and pilot training. An unintentional consequence was that non-combat and technical fields accrued a disproportionately large share of talented, skilled, and socially stable men. The Army Air Forces proved especially masterful in skimming the cream of personnel intakes by setting high qualifications and retaining everyone, even men who failed pilot training. In contrast, specialties such as “infantryman” had no civilian corollary. Many soldiers therefore entered the combat arms by virtue of not being qualified for other duties. Re-prioritization of physical ratings over occupational skills in 1944, in response to a dire shortage of combat troops, changed this dynamic somewhat.

"’Square Deal’ or Not?," What the Soldier Thinks, no. 16 (September 1945).

The assignment system worked well enough for the organization, but many soldiers expressed dissatisfaction. Frustration tended to be most acute amongst skilled and educated men whose self-images did not match their new realities. Other aggravations included involuntary job changes and high personnel turnover rates produced by units scrambling to fill shortfalls. Race introduced another dimension. Black men, for instance, were allocated disproportionately to service specialties. The assignment system was ultimately a common source of discontent among enlisted men; one study concluded that it accounted for approximately one-sixth of all soldier complaints about not getting a “square deal.”

Officer Accessions

Officer accessions worked differently. The officer class, numbering in the hundreds of thousands, was smaller and more selective than the enlisted population. Four pathways to entering that class existed: the United States Military Academy, Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) programs, direct commissioning, and Officer Candidate Schools (OCS). Combined, the first three produced less than half of officers during WWII. The most common pathway was an OCS program. Created in 1941, OCS turned enlisted men into officers through twelve- to seventeen-week courses. It also provided a bridge across the officer-enlisted social chasm, though crossing opportunities narrowed in late 1943 to prevent a junior officer surplus.

Qualifications for OCS included an AGCT score in one of the top two brackets, “proven leadership ability,” and completion of basic training.5 Roughly 75 percent of candidates graduated by performing adequately in academics, cadre evaluations, and peer ratings.6 Graduates received a commission as a Second Lieutenant and, informally, a “90-Day Wonder” moniker. Although many performed well in time, 90-Day Wonders routinely inspired complaints among noncoms because they rarely arrived at units with the tactical competence to lead men in battle.

Promotions

Servicemembers continued navigating the army’s personnel systems after basic training. Most hoped for a promotion that would bring enlarged authority, better pay, and more privileges. Servicemembers competed for promotions within their units when vacancies opened in the Table of Organization. This document established a unit’s strength by duty position and grade. Determining which men to promote depended chiefly upon the judgment of a unit’s commanding officer.7 A commander’s first consideration was supposed to be seniority. The longer a man’s service, the more likely he was to secure a promotion. Manner of performance was also important, yet it was difficult to measure in any standard and objective way. For enlisted men, the recommendations of noncoms and junior officers determined merit. For officers, biannual efficiency reports and a superior’s impressions did the same.8 Men seeking to get ahead in this system “bucked” for promotion by drawing positive attention to themselves or by politicking. Both were widely practiced and widely condemned.

Satisfaction with promotion systems correlated strongly with success in them. Those who earned promotions were better disposed to the processes, but dissatisfaction was widespread (see WST, no. 14 (June 1945)). Systemic preference for seniority and conformity over merit vexed soldiers who shared widely held beliefs in egalitarian, citizen-soldier ideals. One postwar study concluded that the army was “not too successful” in convincing men that promotions were “based on merit or were the reward for exceptional achievement.”9 An old adage summed up the main source of frustration: promotion depended “more on who you know than on what you know.”

Samuel A. Stouffer et al., The American Soldier: Adjustment During Army Life, vol. I (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1949), 233.

Conclusion

Readers exploring The American Soldier in World War II collection should bear in mind tensions between the army’s requirements and people’s desires. The army’s industrial approach did not always endear itself to servicemembers because it prioritized the organization’s needs. Consequently, some men came to feel that they did not receive a “square deal.” Stories abound of airplane mechanics winding up in the infantry and of competent soldiers losing out on promotions to sycophants. Such feelings and anecdotes, though not representative of most soldiers’ experiences, were byproducts of a giant war machine’s operations. Yet the army’s systems proved sufficient for fighting World War II. Also, they were not entirely insensitive to servicemembers, as the studies by Samuel Stouffer and his colleagues show. Servicemembers ultimately learned how to function within the systems, playing for advantage where they could and accepting their lots or complaining where they could not.

Garrett Gatzemeyer

The University of Kansas

Further Reading

Lance Betros, Carved from Granite: West Point since 1902 (Texas A&M University Press, 2012).

G. Q. Flynn, The Draft, 1940-1973 (University Press of Kansas, 1993).

Lee Kennett, G.I.: The American Soldier in World War II (University of Oklahoma Press, 1987).

Peter Mansoor, The GI Offensive in Europe: The Triumph of American Infantry Divisions, 1941–1945 (University Press of Kansas, 2002).

Milton M. McPherson, The Ninety-Day Wonders: OCS and the Modern American Army (United States Army Officer Candidate Alumni Association, 1991).

Robert R. Palmer, Bell I. Wiley, and William R. Keast, eds. The Army Ground Forces: The Procurement and Training of Ground Combat Troops (Center of Military History, 1991).

Studs Terkel, ”The Good War”: An Oral History of World War Two (Pantheon, 1984).

M. E. Treadwell, The Women's Army Corps (Center of Military History, 1991).

Select Surveys & Publications

S-44: Attitudes toward Branch of Service

S-116: Planning Survey

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 3 (February 1944)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 4 (March 1944)

- Lee Kennett, G.I.: The American Soldier in World War II (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987), 46-47.

- Robert R. Palmer, "The Procurement of Enlisted Personnel: The Problem of Quality," in The Procurement and Training of Ground Combat Troops (Washington: Center of Military History, 1991), 5.

- Kennett, 34-36.

- Palmer, 6-9.

- William R. Keast, "The Training of Officer Candidates," in The Army Ground Forces: The Procurement and Training of Ground Combat Troops, ed. Robert R. Palmer, Bell I. Wiley, and William R. Keast (Washington: Center of Military History, 1991), 329. See also Milton M. McPherson, The Ninety-Day Wonders: OCS and the Modern American Army (Ft. Benning: United States Army Officer Candidate Alumni Association, 1991), 86-95.

- Ibid., 344.

- Stouffer et al., 259.

- Ibid., 271.

- Stouffer et al., 413.

SUGGESTED CITATION: Gatzemeyer, Garret. “Assignment & Promotion.” The American Soldier in World War II. Edited by Edward J.K. Gitre. Virginia Tech, 2021. https://americansoldierww2.org/topics/assignment-promotion. Accessed [insert date].

COVER IMAGE: "Training, Action! Landing Operations," Newsmap 1, no. 24 (5 October 1942). Army Orientation Course, Special Service Division, Army Service Forces, War Department. Courtesy of NARA, 26-NM-1-24b, NAID 66395048.