Air Combat

The global nature of World War II saw American troops deployed around the world in the fight against fascism. While the bulk of US troops fought the enemy with their feet firmly planted on the ground, a minority took the fight against the enemy into the skies. These airmen occupied a unique place in the US military; generally afforded elite status, their lives differed sharply from those of the majority of combat troops. Airmen usually lived behind the front lines and often had access to luxuries denied other combat branches.

The relative safety of their bases, however, contrasted sharply with combat missions that exposed these men to myriad perils, from freezing temperatures to flack and enemy fighters. Combat airmen suffered casualty rates significantly higher than did their ground-based counterparts, particularly crews of heavy bombers engaged in strategic attacks in Europe. While airmen’s experiences could vary dramatically depending on their operational theater, the types of missions they flew, and their occupational specialty, they generally enjoyed higher morale than ground-based troops, exhibited a high level of job satisfaction, and believed they played an important role in the war effort.

“Waves of Consolidated B-24 liberators of the 15th AAF fly over the target area, the Concordia Vega Oil refinery, Ploești, Romania, unmindful of bursting flak, after dropping their bomb loads on the oil cracking plant, on 31 May `44,” Courtesy of Lib. of Congress, digital ID cph.3b43591.

Background and Training

Lieutenant F.W. “Mike” Hunter, Army pilot assigned to Douglas Aircraft Company, Long Beach, California. Photo by Alfred T. Palmer for the Office of War Information, October 1942. Courtesy of the Lib. of Congress, call no. LC-USW36-99.

As a group, Air Corps (later Army Air Force, or AAF) personnel represented an unusually gifted and privileged population. For the majority of the war, Air Corps combat personnel were volunteers, reflecting the War Department’s desire to staff the Air Corps with motivated personnel who believed in their mission. Demographically, they were more educated and came from more privileged socioeconomic backgrounds than other troops; during the first two years of the war, the army channeled the best and brightest candidates into the Air Corps.

Candidates had to pass a rigorous series of medical and psychological tests—the notorious “classification battery”—in order to earn acceptance into the branch. If accepted, the Air Corps used candidates’ performance on an additional battery of aptitude tests to sort the young men into specialties before sending them on for training. The vast majority of air crews were white, though several notable units—most famously the Tuskegee Airmen—comprised servicemen of color; African Americans also served the Air Corps in myriad support roles around the world.

While all combat personnel took part in rigorous training, pilots, navigators, and bombardiers were subject to the most taxing programs. With washout rates approaching 40 percent for pilot trainees, and 12 to 20 percent for bombardiers and navigators, only the best qualified and most skilled candidates made it through to combat squadrons. The combination of rigorous classroom assessment and challenging practical training quickly highlighted the men best positioned to succeed in the air; lower-scoring candidates were assigned to be flight engineers or gunners, and many failed pilots ultimately saw service as bombardiers or navigators or were transferred to the Infantry.

Morale & Job Satisfaction

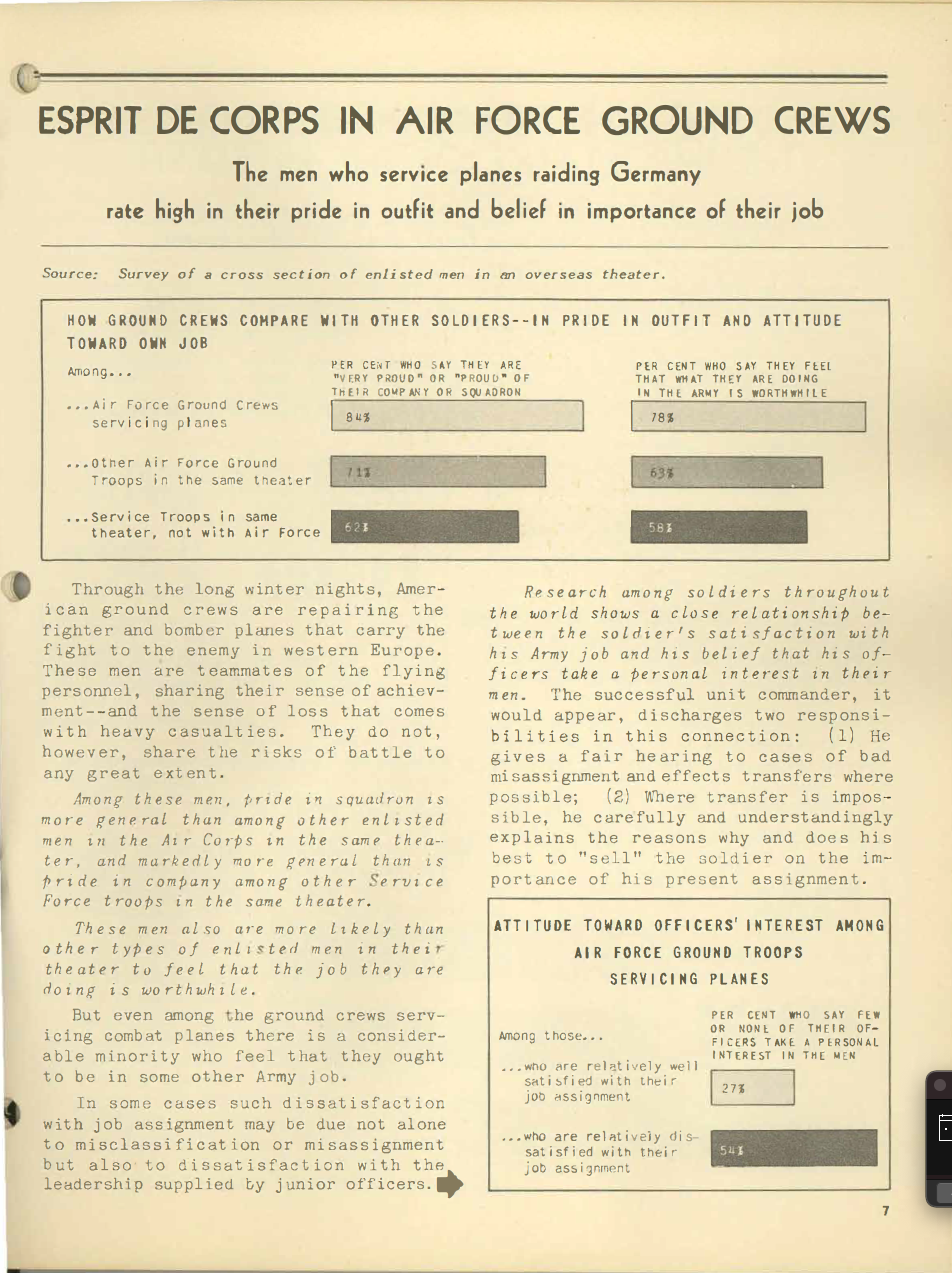

These background conditions resulted in airmen generally enjoying higher morale than the majority of combat troops, though airmen were far from uniform in their perceptions. All US pilots were officers and more than half of all flying personnel were commissioned, while enlisted airmen seldom held a rank below sergeant. Officers exhibited higher morale and job satisfaction than did their enlisted peers, many of whom served on ground crews. Flying personnel represented outliers in a military numerically dominated by enlisted personnel, in the process enjoying the privileges associated with higher rank and status. Ground crews and other support personnel often exhibited different perceptions, in many cases shaped by the theater in which they served. Eighth Air Force crews living in the relative comfort and safety of England generally reported more job satisfaction than did crews in the Pacific, for instance.

For pilots, navigators, bombardiers, flight engineers, and gunners, the nature of their responsibilities helps explain the generally high morale they exhibited. Flight personnel served for a defined tour of duty, usually measured in missions. This policy stood in stark contrast to other combat arms, in which troops served for the duration of the conflict. While airmen were subject to significant risk during their tours—indeed, suffering casualty rates higher than other combat arms—having a defined endpoint to their service provided a goal towards which to work, and a sense of certainty denied the average soldier.

The close relationships forged within squadrons and crews also improved morale. Aircrews lived and worked together, leading to a clear sense of group identification. Airmen enjoyed better relationships between officers and enlisted than the norm, particularly within aircrews. While familiarity certainly bolstered these relationships, so too did the leadership qualities exhibited by pilots and flight, squadron, and group leaders. Bomber crews were often passionately devoted to their pilot, who shared the same risks they did. In a similar vein, the officers leading squadrons and groups usually led from the front, flying combat missions with their men. The presence of high-ranking officers—Colonels and, at times, Generals—in the bomber stream or fighter flight highlighted the shared burden airmen shouldered and differentiated Air Corps combat personnel from ground units, where staff officers often lived and worked behind the front lines.

“Esprit de Corps in Air Force Ground Crews,” What the Soldier Thinks, no. 2 (January 1944).

The nature of the job itself also engendered high levels of job satisfaction. The vast majority of pilots loved flying and derived significant psychological satisfaction from piloting their craft. For many, the dangers of combat only heightened their positive associations, a fact particularly true for fighter pilots. Navigators, bombardiers, and flight engineers possessed significant skill, and a majority took pride in doing difficult work well. Many airmen also hoped the skills they learned in the service would lead to jobs after the war.

Living conditions also bolstered high morale. Particularly in Europe, aircrews usually had good living quarters, good food, and ready access to medical attention. While conditions in the Pacific and North Africa often fell short of those high standards, airmen in those theaters generally enjoyed many of the same basic comforts. Airmen also had a significant amount of autonomy and free time. While combat missions often put them in acute danger, those periods were relatively brief and much of their time was their own. In England, pilots and crew had access to pubs, the company of local women, and passes allowing many to visit London and other large cities. In more remote locales, airmen could still look forward to significant downtime between missions.

Combat & Casualties

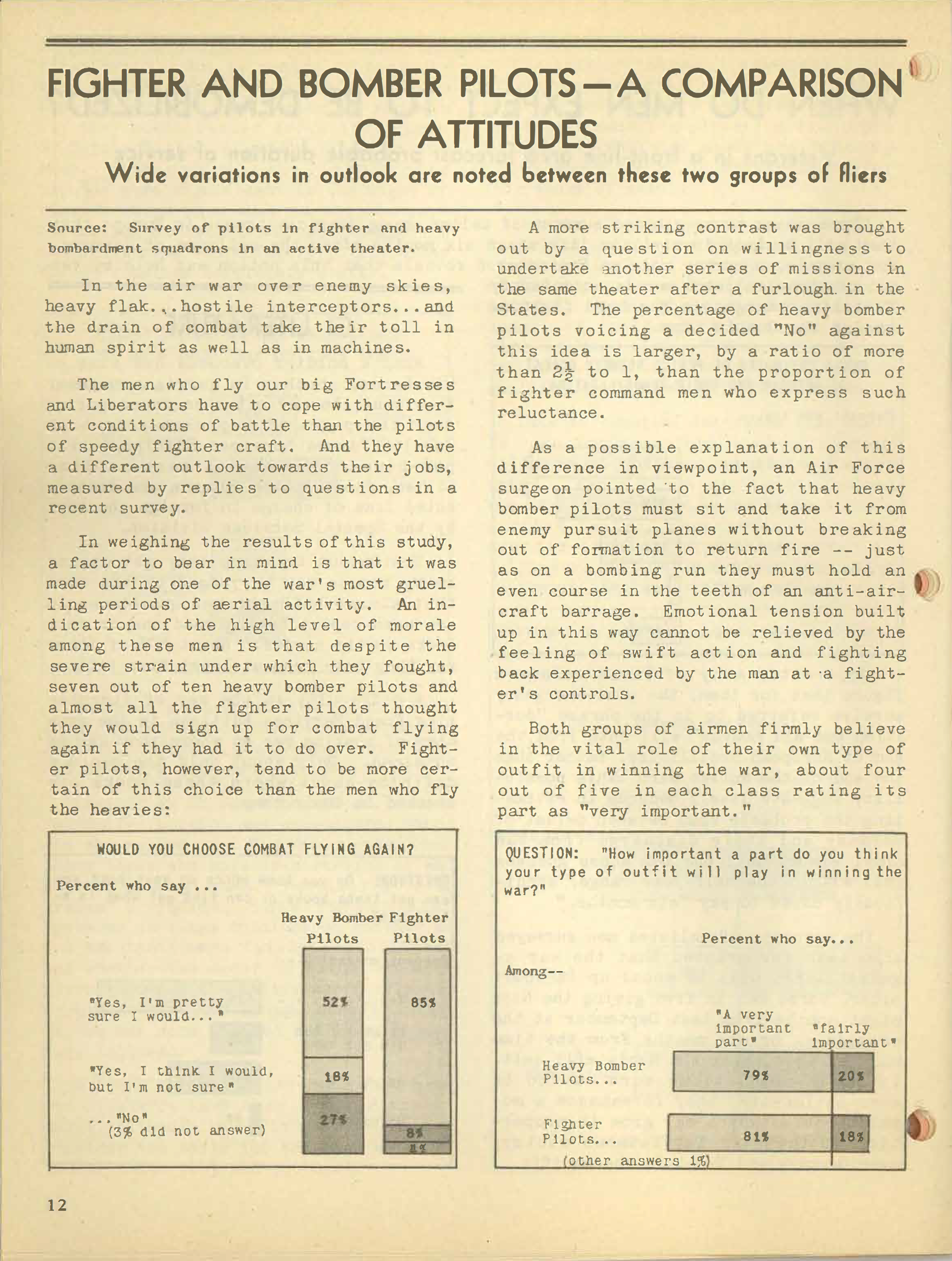

Combat airmen encountered significant differences in their experience of combat. Overall, airmen’s belief in their mission, high levels of job satisfaction, and all-volunteer status resulted in pilots and crews enjoying a more positive outlook than was the norm among U.S. combat troops, even in the face of often-heavy losses. Differences emerge, however, when comparing the experiences of fighter and bomber crews, and different parts of the bomber community. In general, fighter pilots exhibited higher morale than their bomber counterparts. This reflected fighter pilots’ greater freedom and their lower casualty rates. Fighter pilots reacted positively to escort missions and fighter sweeps, but expressed more negative reactions to dangerous bombing and strafing assignments. Within the bomber community, light bomber crews enjoyed the highest morale and heavy bomber crews the lowest. Light and medium bomber crews—flying smaller, twin-engine aircraft often utilized for tactical and short-range strategic strikes—flew shorter missions at lower altitudes, limiting their exposure to extreme cold and enemy activity.

They also had more autonomy and freedom to maneuver than their heavy bomber counterparts, as the latter group usually flew in tight, high-altitude formations. Heavy bombers’ focus on long-distance, daylight, strategic attacks resulted in that group suffering the highest causality rates in the bomber community. Across the Air Corps, crewmen with the most to do—pilots and navigators—enjoyed higher morale than gunners, who had little to do for the majority of most missions. All airmen suffered increased anxiety and stress as their tours progressed. While this trend was most notable in heavy bomber crews, all exhibited a decline in desire for combat and increased tension and stress as their missions mounted.

Air Corps flight crews’ generally positive outlook stands in sharp contrast to the steep losses they suffered. Casualty rates were higher in Europe—particularly in the early stages of the strategic bombing offensive—than in the Pacific, and higher for bomber pilots than their fighter brethren. Overall, however, airmen suffered losses at a significantly higher rate than ground-based combat troops. Much of this fact reflected the dangerous nature of air combat. For heavy bombers especially—forces that shouldered the brunt of the US offensive in Europe before D-Day—deep penetration daylight bombing missions were extremely hazardous. The Eighth Air Force, flying missions from England to the Continent, lost more than 50 percent of its crew strength during the war.

While fighter pilots and airmen serving in other theaters experienced lower casualty rates, combat flying was still very dangerous. Many crews were also lost to accidents and bad weather. Again, airmen serving in northern Europe experienced the worst conditions, but clouds, storms, fog, and high winds could make any flight a challenge. Airmen also had to contend with oxygen deprivation and temperatures that could plunge to more than 60 degrees below zero Fahrenheit on high-altitude missions that could stretch to more than ten hours, a particular challenge for bomber crewmen stationed next to open windows. The Pacific theater posed different challenges, from long-distance navigation over the open ocean to primitive landing fields, crippling heat, and water and insect-borne illnesses like malaria and yellow fever.

“An Eighth Air Force Bomber Station, England—Twas the night before Christmas….and on the day when the 8th Air Force sent more than 2000 heavy bombers to attack Nazi targets behind the lines in the campaign to slow up Rundstedt’s drive. Over the target—the marshaling yards at Darmstadt—flak caught a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress’ and a fragment ripped the bombardier’s leg. Here, wounded bombardier is being removed from the Flying Fortress,” 24 December 1944. Courtesy of NARA, 342-FH-3A-13656, NAID 148728182.

Strategic Bombing

While Air Corps crews flew a wide variety of missions, strategic bombing represented the service’s most prominent role. The strategic air offensive in Western Europe formed a centerpiece of US actions against Germany until D-Day. American pilots also undertook an extensive strategic campaign against the Japanese home islands in 1944 and 1945. These efforts emerged from airpower advocates’ belief that strategic bombing could bring an enemy to its knees, ideally removing the need for a ground campaign. While historians continue to debate the value of these efforts, heavy bomber crews represented the largest population of combat airmen, a population that bore the brunt of Air Corps combat losses. The hard duty these men embraced was reflected in their lower morale and higher levels of stress when compared to other types of combat aircrews. Those negatives notwithstanding, heavy bomber crews exhibited the same qualities—including high levels of job satisfaction, pride in their work, and a strong sense of group identification—that defined the majority of airmen’s service.

Conclusion

During World War II, Air Corps combat personnel faced myriad challenges across all combat theaters. While they benefited from the branch’s all-volunteer composition, rigorous training programs, and high personal motivation, airmen suffered higher casualty rates than did servicemen in other combat branches and struggled with stress and anxiety, particularly as their tours wound down. Diverse in their experiences, airmen were nonetheless united in exhibiting pride in their jobs and a clear belief in their contributions to the war effort.

M. Houston Johnson V

Virginia Military Institute

Further Reading

John McManus, Deadly Sky: The American Combat Airman in World War II (Presidio, 2000).

Richard Overy, The Air War, 1939-1945 (Potomac Books, 2005).

Mark Wells, Courage and Air Warfare: The Allied Aircrew Experience in the Second World War (Frank Cass, 2000).

Select Surveys & Publications

S-134: Field Forces Study

S-135: 8th Air Force Survey

S-136: 8th and 9th Air Force Survey

S-141: Air Transport Command Enlisted Personnel Study

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 8 (August 1944)

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 10 (November 1944)

SUGGESTED CITATION: Johnson, Houston. “Air Combat.” The American Soldier in World War II. Edited by Edward J.K. Gitre. Virginia Tech, 2021. https://americansoldierww2.org/topics/air-combat. Accessed [date].

COVER IMAGE: "Aircraft Insignia," Newsmap 2, no. 22, Overseas Edition (20 September 1943). Army Orientation Course, Special Service Division, Army Service Forces, War Department. Courtesy of NARA, 26-NM-2-22, NAID 66395186.