Entertainment

In the summer of 1944, the popular comedian and radio personality Bob Hope began yet another of his famous tours of military camps for the United Service Organizations (USO). This particular tour made stops in Hawai’i and on small islands all across the Pacific theater, where Hope and his troupe performed 150 shows in two months. American military personnel loved the shows. Hope’s jokes and silly stunts made them laugh and took their minds away from the war for a few minutes. But the routines had a much larger purpose than simple diversion. In a standard part of the show, Hope introduced the troupe’s youngest member, tap dancer Patty Thomas. “I just want you boys to see what you’re fighting for,” he explained to an audience of cheering and whistling men who were, undoubtedly, far more impressed with Thomas’s slender figure and long legs than with her tap-dancing skills.1 Yet, that was exactly the point. Thomas wasn’t on the tour simply because she was a talented dancer. She was there to remind the men of women from home. Even Hope wasn’t there simply to make the men laugh. He—and all forms of entertainment in World War II—reminded servicemembers of home, of everything that they had left behind, and of everything that they hoped to return to at the war’s end. Entertainment gave them something to fight for.

Military commanders in all wars throughout history have understood that morale is essential to a force’s willingness to fight and endure hardship. While good morale depends on many things, including good leadership, clear purposes, and good food, entertainment played a crucial role in the morale of American military forces during World War II.2 Entertainment also served particular purposes for different constituent groups. Of course, entertainment gave servicemembers a break from the stresses and the boredom of war. Radio programs, movie showings, USO shows, and visits from Red Cross women serving donuts all allowed soldiers to think about something besides the war, to relax, and even to laugh. Military officials relied on many forms of entertainment, along with other forms of recreation and religious services, to divert soldiers’ attention from vices that could result in illness or from any activities that might get them into trouble in local communities. In particular, commanders hoped that wholesome activities would distract men from alcohol and prostitution. Community leaders in areas near military bases often appreciated this effort and frequently helped to steer men toward USO clubs or other activities and away from local women and saloons.

Organizing Morale

In the months before the United States entered the war, army officials began to centralize what had previously been a haphazard effort to provide recreation and entertainment for soldiers. During World War I, the military relied on various religious and civic groups to organize morale work, and while their efforts had been appreciated, they had often overlapped and proven difficult to coordinate. As army leaders began to mobilize in the early 1940s for a seemingly inevitable war, they hoped to avoid a similar bureaucratic mess, and organized entertainment and recreation work under the Special Services Division (originally called the Morale Branch).

Soldiers listening to a jukebox, n.d. Courtesy of NARA, 208-LU-35CC-4, NAID 535751.

Special Services managed the Army Exchange System (better known as the PX), provided first-run Hollywood movies to be shown in camp theaters, organized a rapidly growing radio network that featured popular music and informational programs, published Yank magazine (with a worldwide circulation of 2.5 million copies), distributed tobacco and candy to soldiers under fire, organized athletics programs, and operated clubs where soldiers could purchase food, read American newspapers and magazines, play games, and dance with girls from home. The military revived the GI newspaper Stars and Stripes, created in the earlier world war as a newspaper by and for enlisted soldiers. Armed Forces Radio Service produced and distributed live audience programs in coordination with network studios in New York and Hollywood, musical variety shows such as the popular “Command Performance” and “Mail Call,” and several programs hosted by disk jockeys, including “GI Jive” and “Yank Swing Session.” Several programs featured specific musical styles, while others were designed to appeal to particular racial and ethnic groups. “Jubilee,” for example, targeted African Americans, while “Viva America” targeted Latin American and Spanish-speaking soldiers.

Special Services also worked to ensure that GIs could produce their own entertainment. GIs staged and starred in Soldier Shows, a wide range of variety shows, plays, and musical performances, using scripts and song lyrics distributed by Special Services. The most famous Soldier Show, This is the Army, ran on Broadway before General Dwight D. Eisenhower sent the cast of 165 members on a worldwide tour that ultimately raised ten million dollars for relief.3

Home away from Home

Initially, many army officials had hoped to manage all aspects of soldiers’ entertainment themselves. But in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt insisted that civilian organizations be permitted to supplement the military’s efforts to entertain servicemembers. Partly, the military needed the help, especially when the United States began deploying troops to all corners of the world. But, for Roosevelt and many civilian leaders, this military-civilian connection was essential to keeping civilian ideals and values in the minds of military personnel. They envisioned civilian organizations like the USO and the Red Cross as representatives of a concerned American public, as essential civilian influences for men who enlisted or had been drafted for the war’s duration.

"These USO girls eat with some of the men they help entertain. Photo, taken somewhere in France, shows Miss Marian Page, Eastbourne, Sussex, England; Cpl. Robert Buxton, 1505 West Oreland Avenue, Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, and Miss Mary Carnevale, 123 Spring Street, Lodi, N.J., lined up, awaiting mess," 25 July 1944, U.S. Army Signal Corps. Courtesy of NARA, 111-SC-192006, NAID 176888112.

Military entertainment thus linked the military and the homefront in important ways, while providing an outlet for many Americans to contribute time and talent to the war effort. The USO insisted that military life could be demoralizing and disruptive for temporary citizen-soldiers, and acknowledged public concerns about the long-term consequences of militarization. Given these fears, USO leaders argued that the organization would provide “a wholesome atmosphere, the companionship of fine women and girls, recreations that are normal and influences that will keep [servicemen] clean, and worthy.”4 USO clubs were not merely places to spend some free time. They were a “home away from home.” Women played essential parts in entertainment’s function as a reminder of home. Women “working alongside” soldiers and sailors, one Red Cross worker explained, served as a “small but important point of contact between those men and the women they left at home” and would help the men “readjust themselves to civilian life.”5

Dancing & Donuts

The USO formed in 1941, merging the work of the Salvation Army, Young Men’s Christian Association, Young Women’s Christian Association, National Catholic Community Services, National Travelers Aid Association, and the National Jewish Welfare Board. Domestically, the USO sponsored more than three thousand clubs located near domestic military camps and in urban areas where servicemembers could find free coffee and doughnuts, a place to write home or see a movie, play games, listen to the radio, play records on the phonograph, and—most popularly—a place to dance with young women. Although some USO clubs were racially integrated, and although the USO insisted that it did not discriminate, most clubs were racially segregated, with around three hundred clubs catering specifically to African Americans. The vast majority of military personnel visited USO clubs, and among them, more than eight in ten insisted that the clubs were “absolutely necessary” or “of great importance” (Survey 72, Q.25).

Army and Navy USO in downtown Honolulu, 6 Feb. 1945. Courtesy of NARA, 111-SC-347375, NAID 176250386.

The USO’s Camp Shows program dispatched live entertainment to military camps in the United States and to all of the war’s theaters. More than seven thousand performers staged over 428,000 shows throughout the war and immediate postwar years, many of them traveling abroad on what the USO called the Foxhole Circuit. Most Americans knew of famous performers like Marlene Dietrich, Humphrey Bogart, Lena Horne, and Judy Garland, who volunteered to tour for the military. But the vast majority of performers—98 percent of them—were unknown, amateur singers, dancers, and performers who wanted to contribute their talents to the war effort and hoped that their wartime exposure might ultimately boost their careers. Servicemembers were far more likely to see a troupe of six or seven performers who combined their talents into a show that featured singing, acrobatics, jokes, music, and perhaps even a ventriloquist show, than they were to see a famous actor or musician who stole the headlines.

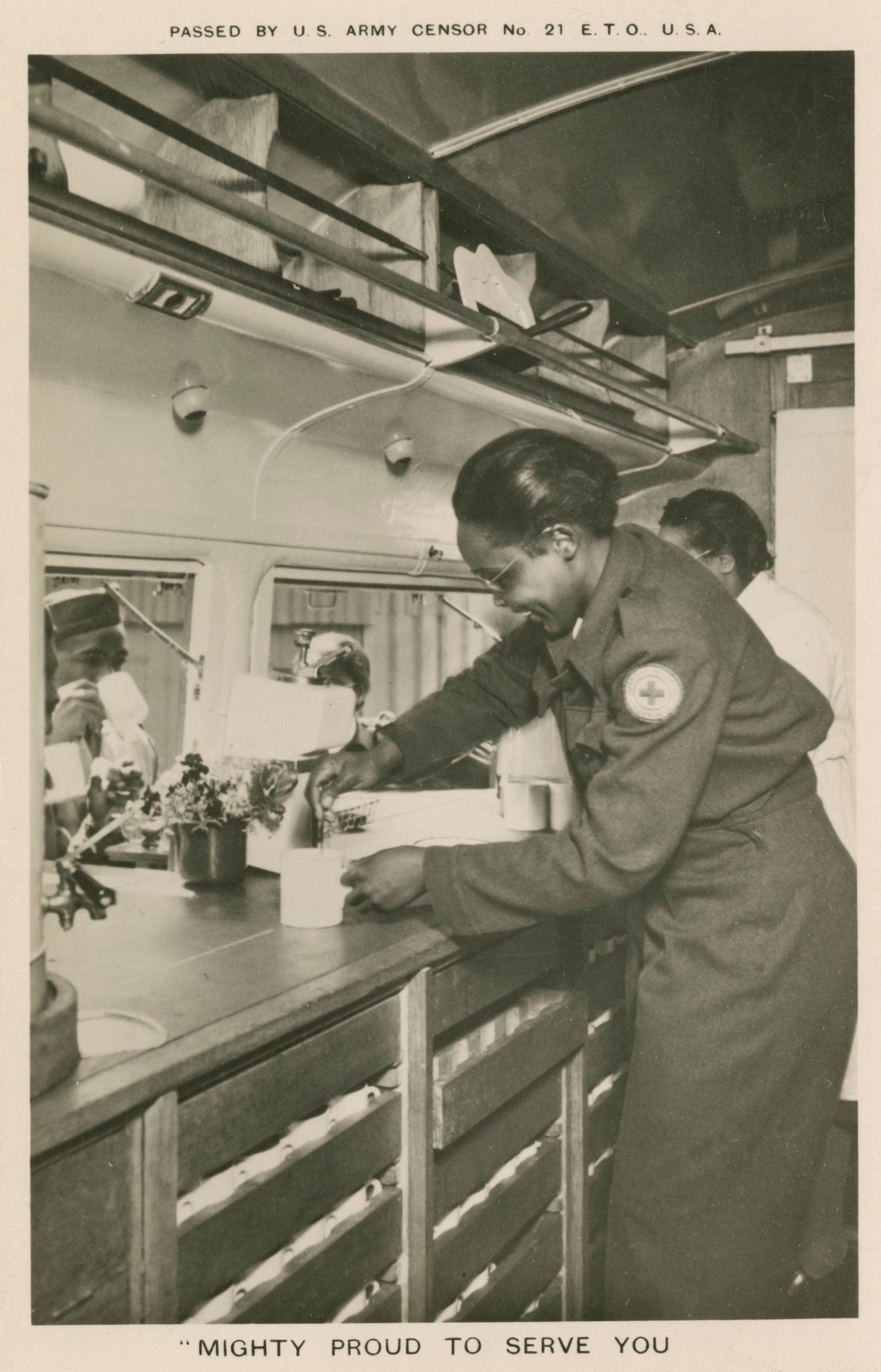

The Red Cross also provided a significant portion of military entertainment in the war zones. At the height of its wartime operations, the Red Cross ran nearly one thousand clubs on and near military camps in all of the war’s theaters. Similar to USO clubs in the United States, young American women operated Red Cross clubs. Clubs featured snack bars, places to relax with newspapers from home, games, musical equipment, and a host of scheduled activities. Some of the larger clubs opened in requisitioned hotels and provided overnight accommodations, laundries, and barbershops. The famous Rainbow Corner Club in London could serve up to 60,000 meals in a single 24-hour period. To reach men who could not leave the front and men in isolated areas, the Red Cross operated more than 300 Clubmobiles, converted Jeeps and buses equipped with coffee and donut machines. Operated, and often driven, by American women, Clubmobiles were a big hit with the men who flocked to them—eager for donuts and coffee to be sure, but mostly eager for a glimpse of young women from home.

"Mighty Proud to Serve You"; reverse side of postcard, "American Red Cross Clubmobile staffed by American Girls bring hot coffee and doughnuts to U. S. Forces overseas," c. 1945. Courtesy of Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Object No. 2010.36.5.36.

In the years after World War II, the military gradually assumed more control of entertainment. Special Services clubs slowly replaced Red Cross clubs and visits by Red Cross women to the field, leaving the organization to focus on relief and assistance to military personnel. The USO continues to provide a wide range of services for military families, but it eventually focused its entertainment efforts on celebrity tours, leaving the Armed Forces Professional Entertainment Office to coordinate tours of amateur and lesser-known talent. Even with these changes, the mix of military- and civilian-provided entertainment established during the war remained in the years to come.

Kara Dixon Vuic

Texas Christian University

Further Reading

Kara Dixon Vuic, The Girls Next Door: Bringing the Home Front to the Front Lines (Harvard University Press, 2019).

James J. Cooke, Chewing Gum, Candy Bars, and Beer: The Army PX in World War II (University of Missouri Press, 2009).

Meghan K. Winchell, Good Girls, Good Food, Good Fun: The Story of USO Hostesses during World War II (University of North Carolina Press, 2008).

Select Surveys & Publications

S-63: Morale and AWOL Study

S-72: USO Clubs

S-189: Radio Study

S-227: Radio Study

What the Soldier Thinks, no. 11 (January 1945)

- Kim Guise, “Patty Thomas: ‘What You are Fighting For,’” April 8, 2020, National World War II Museum (accessed August 13, 2020).

- Robert Westbrook argues that Americans were motivated more by personal obligations than by political obligations. In that respect, entertainment and its connections to home played perhaps a more significant role in maintaining morale among the US military than among other combatants. See Why We Fought: Forging American Obligations in World War II (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Press, 2004).

- Lowell Matson, “Theatre for the Armed Forces in World War II,” Educational Theatre Journal 6, no. 1 (1954): 1-11.

- “To New York City Parents and Neighbors” pamphlet, 4-5, JDR Jr. Address, July 8, 1941, Series P Welfare-General, RG 2 OMR, RFA, Rockefeller Archive Center.

- Eleanor (Bumpy) Stevenson with Pete Martin, “I Knew Your Soldier” Saturday Evening Post, October 28, 1944, 70.

SUGGESTED CITATION: Vuic, Kara Dixon. “Entertainment.” The American Soldier in World War II. Edited by Edward J.K. Gitre. Virginia Tech, 2021. https://americansoldierww2.org/topics/entertainment. Accessed [date].

COVER IMAGE: “Soldiers listening to a jukebox,” 1942. Exhibit Section, Picture Division, News and Features Bureau, New York Office, Overseas Operations Branch, Bureau of Special Services, Office of War Information. Courtesy of NARA, 208-LU-35CC-4, NAID 535751.