Legacy

For the hundreds of social scientists who decamped to Washington after Pearl Harbor, the war was no mere interruption. The chance to join the fight was an opportunity to mix service and science. The scholars who mobilized for the Office of War Information, the Department of Agriculture, and dozens of other civilian and military agencies were, in early 1942, poised to transform their disciplines. Going in, most had no idea. War service, after all, was an exercise in applied urgency, not abstract inquiry. Yet all those social scientists seconded to government units had, by war’s end, forged a new mode of investigation: big interdisciplinary teams working on applied problems. They returned to campus with on-the-cusp ambition, aiming to reproduce the very conditions that had—or so they once thought—interrupted their studies.

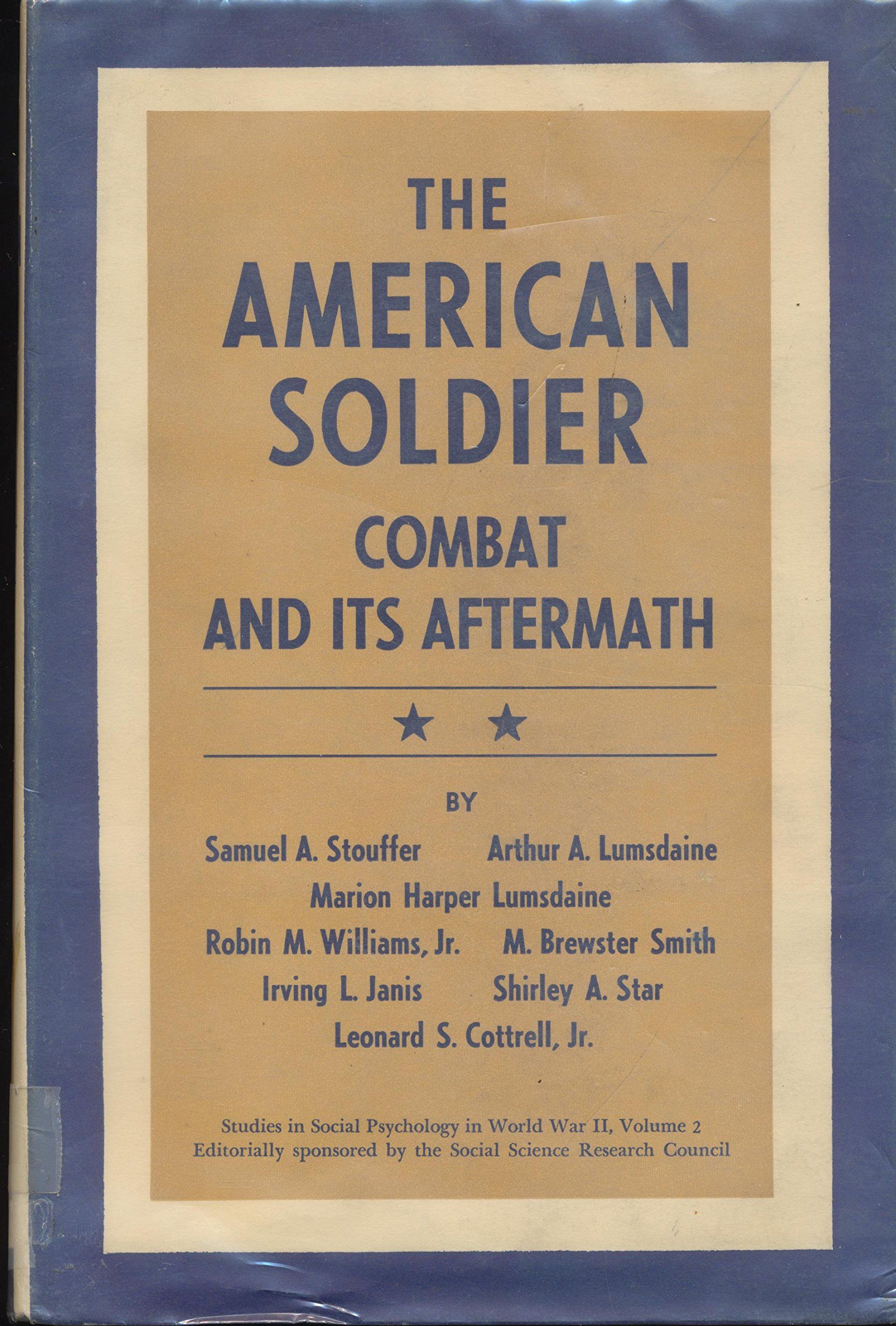

A notable share of that postwar excitement was generated by a single endeavor, the studies of rank-and-file soldiers conducted by the War Department’s Research Branch. The sprawling, multi-disciplinary project epitomized what became, after the war, a new and counterintuitive consensus: If you want generalized knowledge, turn to problem-oriented, sponsored research. The military studies—codified in the four postwar volumes of The American Soldier—showed the way.

Social Science at War

"Samuel A. Stouffer, professor of Sociology at the University of Chicago," n.d., University of Chicago Photographic Archive. Courtesy of the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library, ID apf1-07980.

The Research Branch was established in October 1941, within the War Department’s Morale Division. The idea was to ask enlisted soldiers what they thought about their conditions. Their answers, as summarized, were to be sent up the chain of command. In theory, military leadership would then make adjustments to bolster the troops’ morale. A prominent sociologist from the University of Chicago, Samuel Stouffer, was recruited to head the operation—and without much time to spare. He and his small staff conducted the new unit’s first survey on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor.

Stouffer was an expert in a novel research technique, known as survey research, that commercial pollsters like George Gallup had only just invented in the run up to the 1936 presidential election. The core innovation was to ask questions of a sample, a small subset of the population, which, crucially, the sample otherwise resembled. Stouffer was among a handful of scholars who seized on the new method, adapting its procedures to study academic problems.

Open-ended questions could be asked—and they were—but Stouffer specialized in answers that could be translated into numbers, counted, and graphed. It was important to the general who hired Stouffer that he hailed from the “hard factual side of sociology.” This preference for the quantitative was, in part, an exercise in political tact: The Research Branch was distrusted, and actively resisted, by some top brass. So the cross-tabulated sobriety of Stouffer’s approach was less threatening.

Source: Justification for Existence of the Research Division to Thursday Reports, box 970, RG 330, NARA, NND 813030, NAID 6926560.

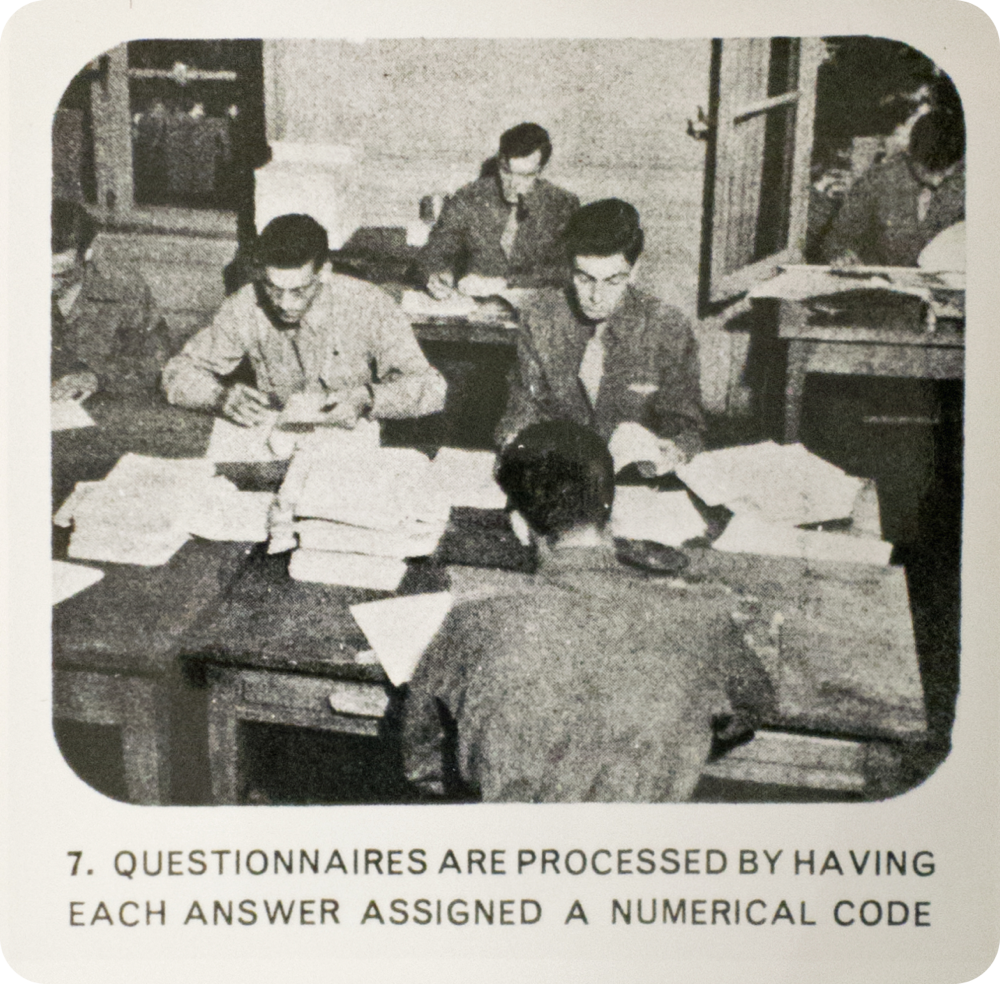

The Research Branch’s Washington-based team of social scientists, pollsters, and support staff—over 120 strong by war’s end—managed a survey operation of astonishing scale. The sheer numbers capture some of this: Over half a million soldiers filled out over two hundred different questionnaires, many with a hundred or more items each. The procedure was to recruit local enlisted men to administer the actual surveys, in central locations like a mess hall. A few dozen fellow enlistees would, in each case, fill out the paper questionnaires with the reassurance of officer-free anonymity. Stouffer’s staff of sociologists and psychologists would pore over the results and fashion them into reports, pamphlets, and a monthly digest, What the Soldier Thinks.

The surveys were the Research Branch’s main tool, though a smaller team was devoted to a second technique, the controlled experiment, which also produced quantitative results. The idea was to test the effectiveness of materials designed to boost soldiers’ morale, notably Frank Capra’s Why We Fight film series. Psychologists, in effect, took their labs to the base. They asked troops how committed they were to the Allied cause, before and after film screenings. Did the films rouse the soldiers’ fighting spirit? Which soldiers, and which titles?

Both operations—the larger survey campaign and the experiments—were designed for immediate, actionable results. There was no pretense, from Stouffer and his staff, that academic ends could be served. Stouffer later admitted as much. The Research Branch, he wrote after the war, was “set up to do a fast, practical job.” If some of its work proved useful to future social scientists, this would be a “happy result quite incidental to the mission of the Branch in wartime.” Indeed, he wrote, “most of our time was wasted, irretrievably wasted.”

Waste, of course, is in the eye of the beholder. To the Branch’s military sponsors, the mundane items—the questions about laundry, beer, or leave policy—were just as important for morale as the questions on, for example, group dynamics, persuasion, or racial attitudes, areas that piqued scholars’ interest. And the Branch’s reports and digests did inform policy. The team’s findings, for example, led to the status-conferring Infantryman’s Badge, and underwrote too a widely praised point system used to guide postwar demobilization. These were the sorts of practical payouts that Stouffer had been hired to produce.

So it is, then, a remarkable fact that Branch alumni, working after the war, were able to extract insight—transformative insight, as it turned out—from the warehoused piles of paper they had generated in such haste.

The American Soldier

The social scientists who demobilized after V-J Day were, on the whole, buoyed by wartime service. For one thing, they had the high-profile example of the natural sciences. The physicists in Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, and Chicago had so successfully marshaled basic research to the ends of war that they had indeed made the decisive difference. No one, of course, confused the social scientists for their celebrated colleagues across campus; the postwar exclusion of the social sciences from the new National Science Foundation, established in 1950, was just one index of low Congressional esteem. But internal to the social science disciplines, among their own ranks, there was gathering excitement about the war-won yields. The sense of a beginning was palpable.

The proclamation that American social science could, or would soon, mimic the objectivity of natural science had already been issued for decades. But this assertion came to feel more plausible in these early postwar years. This was, partly, a generational effect: The Depression had thinned out university ranks and stemmed the flow of foundation dollars. Almost overnight, the war mobilized hundreds of young social scientists, some interrupting their graduate studies, to join the federal research bureaucracy. Thanks to the university system’s rapid postwar expansion—fueled in part by the GI Bill—young returnees swelled the ranks of sociology and psychology departments. For many, the Washington service was a formative break with their discipline’s past.

Born in July 1918 and educated at the University of Chicago, Arnold M. Rose was one of a number of rising social scientists and psychologists recruited to the Research Branch by Stouffer and his team of scholars. These scholars-in-the-making played an important role in the Branch’s overseas expansion. Rose was elevated while in his mere mid-twenties to chief study director in the Mediterranean Theater. For his work with Fifth Army neuro-psychiatric combat casualties, aimed at improving mental health screening and calculating a replacement timetable to prevent “combat exhaustion,” he was awarded a Bronze Star. After discharge, he resumed graduate studies, like most of the young members of the Branch, at the University of Chicago and in 1949 joined the sociology faculty at the University of Minnesota. Courtesy of the University Archives, University of of Minnesota Libraries, DSL ID: una573913.

The war’s big, counterintuitive lesson was that applied work could yield important findings and, perhaps especially, methodological dividends. The Research Branch and its counterparts throughout the wartime government proved to be ideal incubators for a new mode of inquiry: team-based, cross-disciplinary, and staff-supported. The most promising methods, like survey research, required big, well-funded teams in place of the lone-wolf, chair-bound model that had (allegedly at least) prevailed before. By the early 1950s, the belief that organized, multi-disciplinary projects could yield results of theoretical promise and quantitative sophistication was a commonplace among the new social science elite. They even adopted a new name, with a boost from the Ford Foundation, to designate that belief: the behavioral sciences.

The most inventive idea developed in the volumes is relative deprivation. Stouffer and his colleagues used the concept to explain apparent puzzles in the survey data, such as Black soldiers reporting higher satisfaction in Southern camps than Northern ones. The key insight was that soldiers—and by extension all of us—place greater weight on the comparisons we have available to us, rather than on some objective scale. Thus, the Black soldiers in the South compared themselves to civilian Southern Blacks, and found their own lot comparatively privileged. The concept of relative deprivation was instantly influential, and it remains so today.

An innovation that was arguably even more important was the Branch’s invention of new survey methods. Cornell sociologist Louis Guttman developed a technique, since named for him, that helped to quantify attitudes and opinions. His basic insight was that survey questions could be bundled in a deliberate way, with answers ranging from weak/low to strong/high. Soldiers, for example, were asked about fear on the battlefield, in a series of yes/no questions. Each item asked about an elevated level of fear, from no reaction to “violent pounding of heart” to a “sinking feeling” to “trembling all over.” The presumption was that any infantryman who reported trembling would also report the weaker symptoms like heart-pounding, so that their “yes” answers could be summed and compared with others. Guttman scaling, as described in The American Soldier, was quickly embraced by social scientists and pollsters.

More broadly, the Stouffer group’s emphasis on prediction—on the use of survey responses and other data to establish educated guesses about the future—proved widely influential. Stouffer and his team, for example, surveyed soldiers felled by mental illness—“neuropsychiatric casualties,” in military parlance—to develop a screening survey for new draftees, intended to weed out recruits likely to buckle. In that case and in others reported in the volumes, the idea was to mine survey results for patterns which could in turn be used to predict future outcomes. Some of the Branch findings, including on psychiatric risk, set the agenda for the new subfield of military sociology, and went on to affect war policy well into the Vietnam era.

Stouffer oversaw the work on the American Soldier books, supported by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation. As he noted in his introduction, the project was built on a store of data “perhaps unparalleled in magnitude in the history of any single research enterprise in social psychology or sociology.” Each volume was, fittingly, produced by a team of scholars who—in almost every case—had served in the Branch. The first two centered on the surveys, reanalyzed by Stouffer and his team in offices at American University, and were published together in 1949 as The American Soldier. The third and fourth books—on the film experiments and methods, respectively—appeared soon after. The official name of the four-volume set, Studies in Social Psychology in World War II, was rarely used, even then. The American Soldier, in practice, came to refer to the whole endeavor.

The four volumes of analyzed Research Branch work were the quintessential expression of the new postwar rigorism. In their chart-filled, bookshelf-spanning heft alone, they validated the nascent behavioral sciences movement. The volumes were published just as the Cold War re-opened the federal-funding sluices. One result was a remobilization of social scientists, many of them veterans of the Branch and the other wartime agencies, who took up military-sponsored research on behalf of the new national security state. The American Soldier was a published testament to the yield that science—and not just the free world—could expect in return.

The books sold surprisingly well. They were widely and immediately recognized as totemic, as exemplars of the “new” social science which the studies, indeed, went on to legitimate. The positive reviews pointed to the substantive findings—notably relative deprivation—as well as methodological innovations, such as the scaling of survey results. “Why was a war necessary,” asked one reviewer in plaintive praise, “to give us the first systematic analysis of life as it really is experienced by a large sector of the population?” The negative reviews (and there were fewer of these) faulted the studies for their ponderous recitation of the obvious—and for overselling the predictive power of the social sciences. One reviewer, a sociologist, complained of the Stouffer group’s “overpowering obsession with the physical sciences,” while another, the historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., cited the “whirl of punch cards and IBM machines” as a harbinger of top-down social control.

But everyone, boosters and detractors alike, understood the real stakes. The soundness or originality of the books’ social-psychological generalizations wasn’t the issue. The American Soldier was, instead, an elaborated declaration that (as one rapt reviewer put it) “social science is coming of age.” Thus the Research Branch work stood for the promise, and also the peril, of the new “behavioral” sciences.

Jefferson Pooley

Muhlenberg College

Further Reading

John A. Clausen, “Research on the American Soldier as a Career Contingency.” Social Psychology Quarterly 47, no. 2 (1984): 207–13.

Jean M. Converse, Survey Research in the US: Roots and Emergence, 1890–1960 (University of California Press, 1987), 165–71, 217–24.

Ellen Herman, “Chapter 3: The Dilemmas of Democratic Morale,” The Romance of American Psychology: Political Culture in the Age of Experts (University of California Press, 1995), 48–82.

Robert K. Merton and Paul F. Lazarsfeld, eds. Continuities in Social Research: Studies in the Scope and Method of The American Soldier (Free Press, 1950).

Joseph W. Ryan, Samuel Stouffer and the GI Survey: Sociologists and Soldiers during the Second World War (University of Tennessee Press, 2013).

Libby Schweber, “Wartime Research and the Quantification of American Sociology. The View from The American Soldier,” Revue d’Histoire des Sciences Humaines 6, no. 1 (2002): 65–94.

Social Science Research Council, "Studies in Social Psychology in World War II: The Work of the War Department’s Research Branch, Information and Education Division," Items 3, no. 1 (March 1949), reprint May 8, 2018.

Select Surveys & Publications

PS-I: Attitudes in One Division

Adjustment during Army Life, vol. I (1949)

Combat and Its Aftermath, vol. II (1949)

Experiments on Mass Communication, vol. III (1949)

Measurement and Prediction, vol. IV (1950)

SUGGESTED CITATION: Pooley, Jefferson. “Legacy.” The American Soldier in World War II. Edited by Edward J.K. Gitre. Virginia Tech, 2021. https://americansoldierww2.org/topics/legacy. Accessed [date].